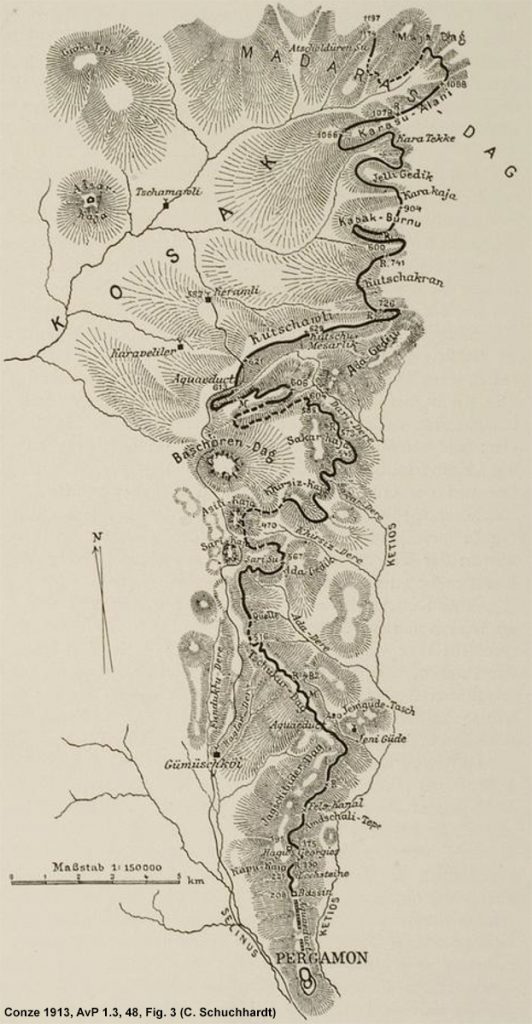

The water systems which supplied running water to the ancient city have been a topic of interest since the early years of the Pergamon Excavation. In 1886, F. Gräber initiated the first research on water systems around the Pergamon city hill, and further studies were carried out by C. Schuchhardt, who travelled in the surroundings of Pergamon for many years and described the topography, landscape, and ancient remains, including some water supply systems (Fig. 1). The most extensive work on the Pergamene water systems was published in 2001 by G. Garbrecht, following long years of research since the 1960s. His important study encompasses aqueducts, channels, and water pipelines supplying the ancient city hill with running water. In 2015, K. Wellbrock published his comprehensive work on the water systems within the city, including cisterns, channels, water pipelines, stamped water pipes, and the typology of Pergamene water pipes.

After many years of research in the western lower Kaikos Plain, the focus of the ‘Umlandsurvey’ within the TransPergMicro project has shifted to the north and the east of the city, including the Ketios (Kestel) valley and its surroundings. Except for the works of Schuchhardt and Garbrecht, most of these areas remained ‘terra incognita’ until this field season. Alongside other discoveries, one of the areas investigated during the survey is the ‘Kireçligedik Mevkii’, a pine forest about 1 km northwest of Gökçeyurt village, where the remains of the foundations of an aqueduct and the corresponding water pipelines were found on the sides of a recently opened forest trail (Fig. 2). The aqueduct, which is located on a narrow ridge between two hills, was probably built to bridge the difference in height while crossing the ridge and ensure the constant flow of water through the water pipes. The only preserved remains in this area are the foundations and some ashlar blocks of different sizes, worked in different techniques, which can be assigned to the aqueduct (Fig. 3). In the continuation of the axis of the aqueduct, a water pipeline can be traced for about 150 m in southeast direction, partially through in-situ remains (Fig. 4). However, no water pipeline could be located on the hill to the northwest; our knowledge on the water pipeline here is based solely on the villagers’ accounts, who said that they saw fragments of water pipes on the hill.

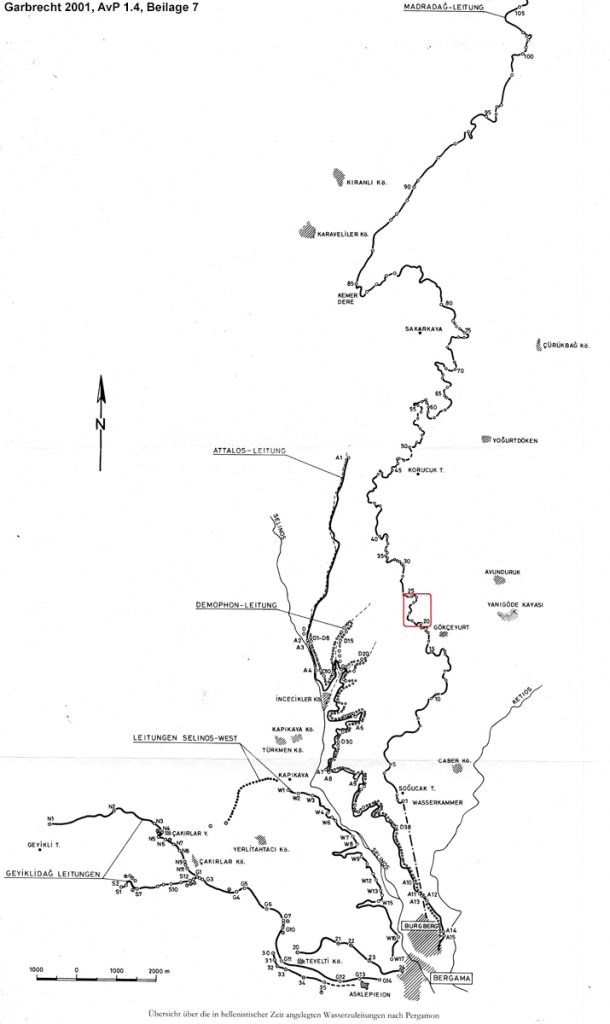

According to the map shown here, this very part of the water supply system most likely belonged to the Madradağ-Pipeline (180–160 BCE) and can be located somewhere between points number 21–24 (Fig. 5). While Schuchhardt also mentioned a collapsed aqueduct in Gökçeyurt, Garbrecht reported that they did not see any remains of an aqueduct visiting the area in 1968. If the aqueduct that Schuchhardt mentioned is the aqueduct (re-)discovered this season, we may assume that Garbrecht was not able to see it as it might have been destroyed in the construction of a forest trail after Schuchhardt’s visit. Nevertheless, it seems likely that the remains of the aqueduct and water pipeline became visible again only recently due to the re-opening of the old forest trail, and therefore re-discovered during the survey this year after Schuchhardt saw it over 140 years ago.

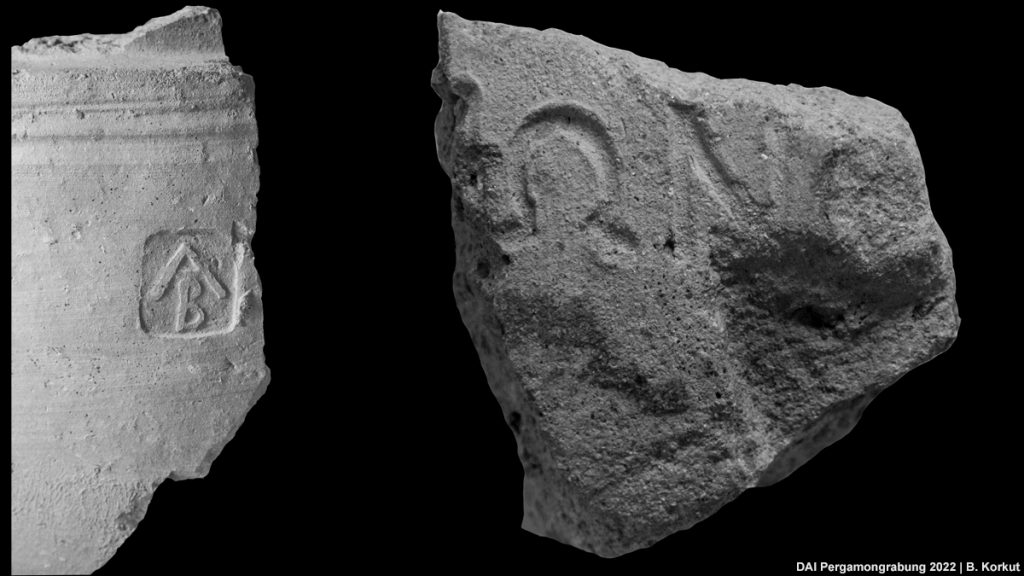

In addition to the three in-situ water pipelines, many other water pipe fragments of different forms and fabrics were observed in close vicinity. In the field, the water pipe fragments were categorized into 10 preliminary groups according to their fabrics and samples were taken from each group for further investigation. According to first observations, they vary in terms of form, width, length, diameter, wall thickness, and fabric, as Garbrecht had suggested before. None of them were stamped, except for two examples, one of which was found approximately 350 m distance from the closest in-situ pipeline. This water pipe fragment bears an “AB” stamp on it, well attested from the ‘Attalos-Pipeline’ (200–190 BCE) (Fig. 6 left). The letters were initially interpreted as an abbreviation for “Αττάλου Βασιλεύουντος” by Schuchhardt, an idea which was abandoned in later years. Even though this stamped fragment was not found in-situ, it is still puzzling and confusing in terms of its findspot, since the closest known parts of the ‘Attalos-Pipeline’ lays approximately 2.1 km away from the ‘Madradağ-Pipeline’ and there were no known examples of “AB” stamps from the ‘Madradağ-Pipeline’.

The second and another puzzling stamped fragment was found approximately 20 m away from the fundaments of the aqueduct. This stamp consists of the letters “ΩΝ”, which may be reconstructed to [ΔΗΜΟΦ]ΩΝ, known from another pipeline named ‘Demophon-Pipeline’ (190–180 BCE) (Fig. 6 right). This pipeline’s closest known parts are also located over a kilometer away from the findspot.

The findspot and the finds with different fabrics, sizes, forms and stamps raised new questions for us to investigate further, this time in the framework of TransPergMicro’s socio-ecological model, from a ceramological perspective rather than a historical hydro-engineering study.

Therefore, a brief study on conceptual models of production of the water pipes for the ‘Madradağ-Pipeline’ will be conducted. The ‘Madradağ-Pipeline’ was most probably constructed in the reign of Eumenes II (197–159 BCE), which was the longest, measuring 42 km in length and supplying the greatest amount of water to Pergamon, it was probably one of the largest projects regarding planning, building and production. As the starting point of this study, Garbrecht’s suggestions on the ‘Madradağ-Pipeline’ and Wellbrock’s water pipe typology will be used as a basis. According to Garbrecht’s calculations, approximately 200.000 individual water pipes were laid for this 42 km long Hellenistic water pipeline. Though Garbrecht was an engineer by education, he also considered the forms, production technique and material of the water pipes themselves. He suggested that the water pipes might have been produced in different areas along the ‘Madradağ-Pipeline’, since they vary in size, form and fabric.

The main aim of the study is to get a first idea on the exploitation of the natural resources such as clay, fuel and water, as well as the space used and time spent during the manufacturing process of approximately 200.000 individual water pipes. Possible scenarios of the production organization and process, questions like the needed amount of workforce, kiln capacities, the temperature and length of firing process will be discussed. This case study may help us to get basic insights into the complex socio-economic process of water pipe production in general and more specifically for a project like ‘Madradağ-Pipeline’, and comprehend the size of the crafts industries, production capacities and processes of ceramic production in Pergamon and its micro-region.

Selected literature on the water systems of Pergamon:

- Garbrecht, Stadt und Landschaft Teil 4, Die Wasserversorgung von Pergamon, AvP 1,4 (Berlin 2001)

- Garbrecht, Die Wasserversorgung des antiken Pergamon, Braunschweigische Wissenschaftliche Gesellschaft Jahrbuch 1991, 1991, 13–28

- Gräber, Die Wasserleitung von Pergamon. Vorläufiger Bericht, Abhandlungen der Königlich-Preußischen Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin (Berlin 1888)

- Wellbrock, Die innerstädtische Wasserbewirtschaftung im hellenistisch-römischen Pergamon, Schriften der Deutschen Wasserhistorischen Gesellschaft. Sonderband 14 (Clausthal-Zellerfeld 2016)