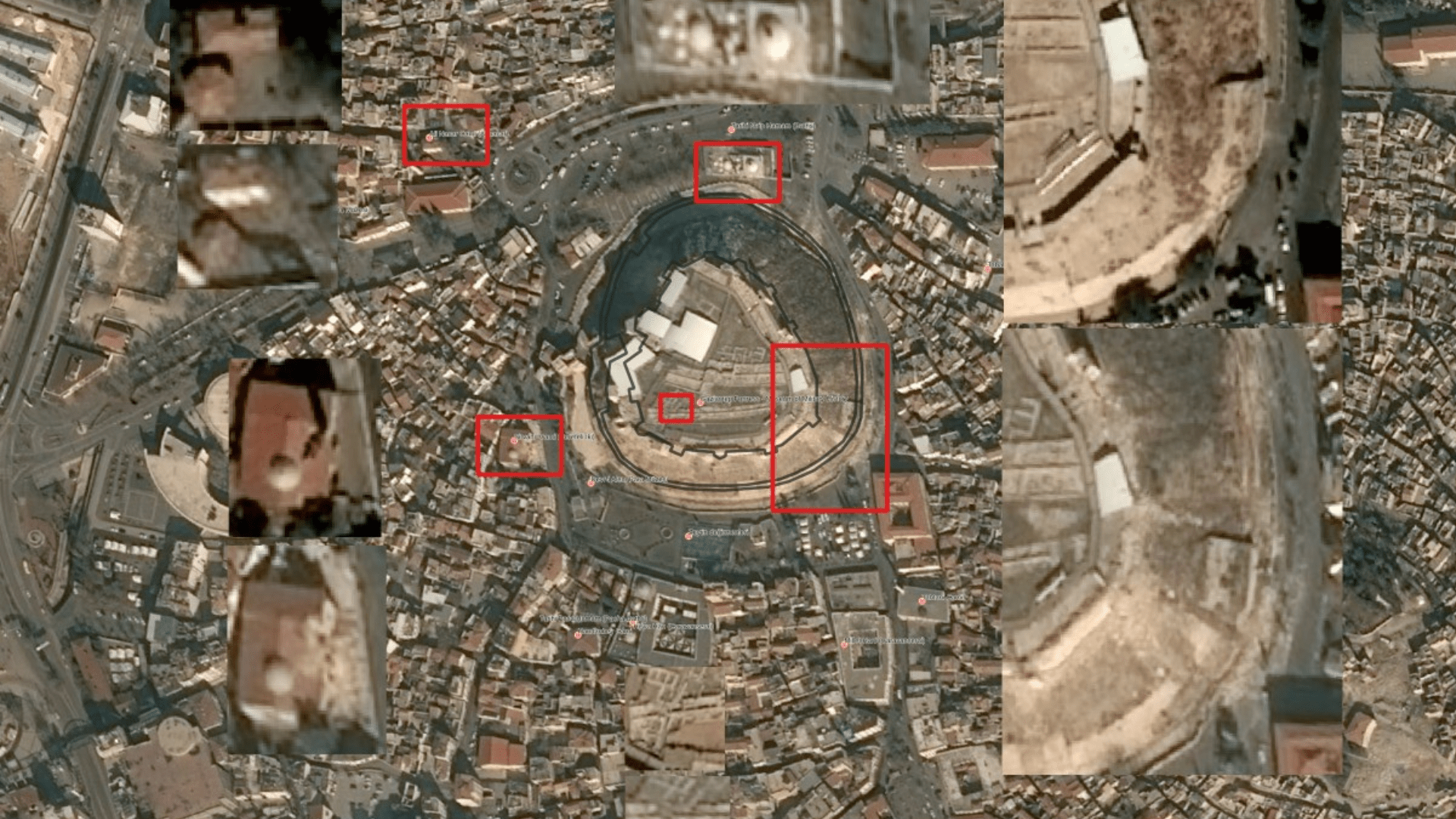

The archaeology in geoarchaeology: examples from field mapping during the 2024 campaign of the physical geography group

During the 2024 joint fieldwork of Freie Universität Berlin and Ege Üniversitesi, we explored the eastern lower Bakırçay plain, mapping geomorphological features. Collaborating with archaeologists, we investigated the ancient Bakırçay River’s shifting course, focusing on fluvial traces and elevations to better understand its historical hydrology. Stay tuned for our findings!