From Boyne to Brodgar – Sacral landscapes and monuments in Ireland and on the island of Rousay (Orkney Islands/Scotland)

Campaign 2019

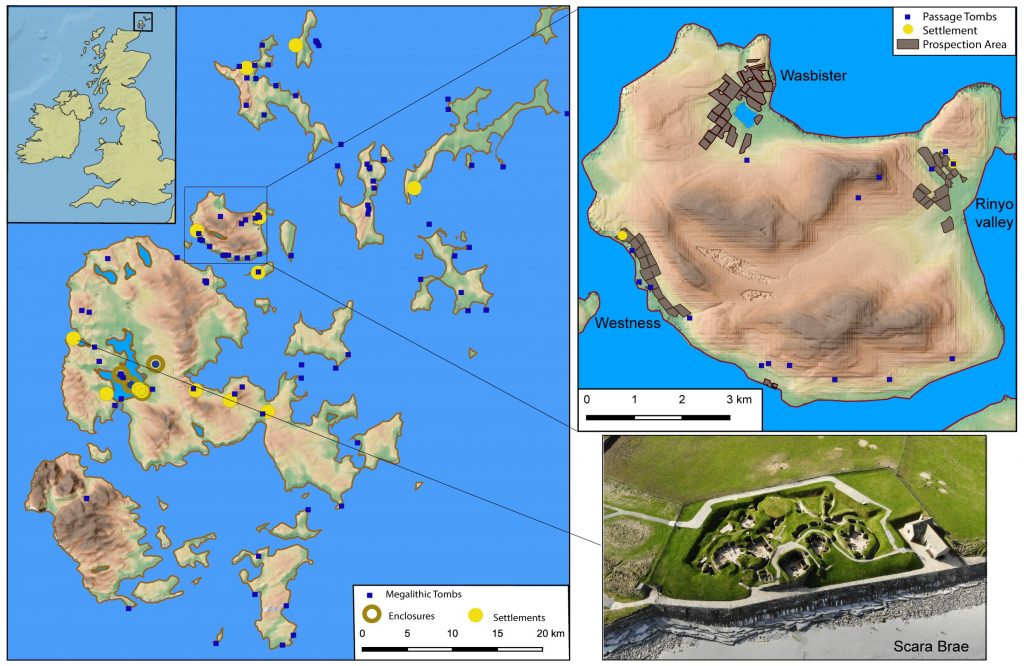

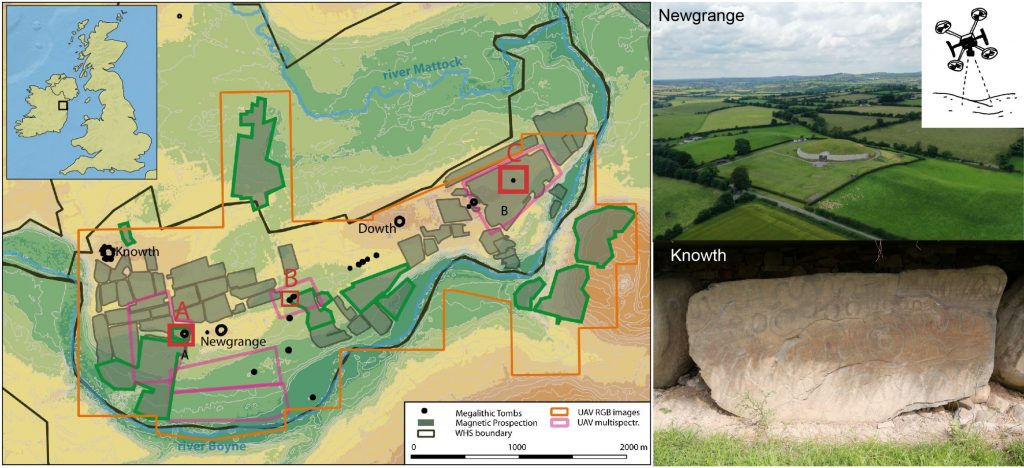

In May and July this year, researchers of the Unit for Survey and Excavation Methodology carried out fieldwork on the Orkney island of Rousay (north Scotland) and in the Boyne Valley, north of Dublin (Figures 1 and 3).

Since 2016, the RGK is part of the „From Boyne to Brodgar“ initiative, which examines the formation of Neolithic cultural landscapes in North-Western Europe. The starting point of this research is the so-called „Atlantic route“ of Neolithisation, which led across the Irish Sea to Ireland, the Isle of Man and on to Scotland. The similarities between the individual regions, which attest to the close links during the Neolithic period, are particularly evident in the monumental architecture, such as megalithic tombs and earthworks.

Our main goal is to explore the socio-ecological relationships within and between the study areas. In order to better understand this complex interrelationship, we have chosen a broad interdisciplinary landscape-based research approach.

This is based on a combination of remote sensing, geophysical survey, soil analyses, drill-core sampling and GIS modelling.

During the 2019 season in Ireland and Orkney, we used both our 5-sensor and our 14-sensor magnetic survey system. These allow us to study large open areas at the same time as places that are harder to reach and access. In addition our drones enable us to take aerial photographs of the study areas and to create 3D-models of the terrain.

Since 2018, we have been cooperating closely with the German Institute for Aerospace (DLR). As part of this joint effort, our colleague Thomas Busche from the DLR visited us in Ireland. Together with him we evaluate satellite images of our study regions (TerraSAR -X) (https://www.dlr.de /hr/).

Our partner institutions in Ireland are the University College Dublin (UCD) (http://www.ucd.ie/archaeology/), Galway National University of Ireland (https://www.nuigalway.ie/archaeology/) and the National Monument Service Ireland (https://www.archaeology.ie/). On the Irish side, the 2019 field season was directed by Stephen Davis of UCD. In Scotland, we work together with the University of the Highlands and Islands (https://www.uhi.ac.uk/en/archaeology-institute/), the National Museum of Scotland at Edinburgh (https://www.nms.ac.uk/national-museum-of-scotland/) and Historic Environment Scotland, the leading public body that investigates, cares for and promotes Scotland’s historic environment. Julie Gibson of the University of the Highlands and Islands helpfully and kindly did all the planning for our work on Rousay in 2019.

Both the Boyne Valley and the Orkney Islands are known for their numerous Neolithic monuments, some of them have survived until today or were uncovered and reconstructed.

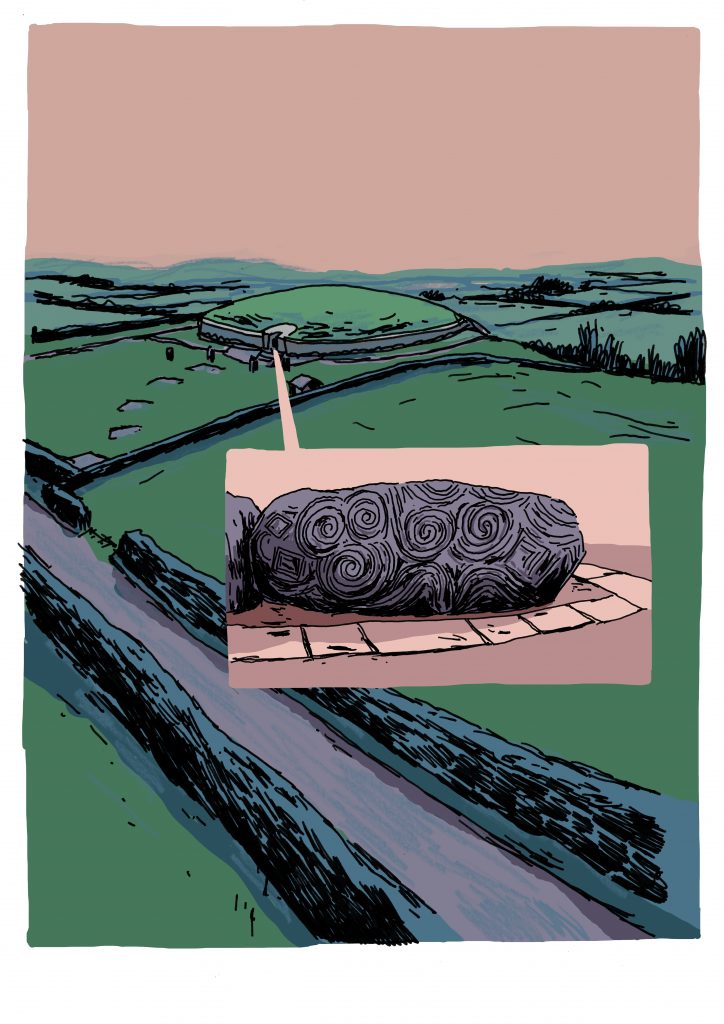

One of Ireland’s best-known archaeological monuments is Newgrange (Figure 3, top right), where the RGK conducts fieldwork in its wider environment. Even though its appearance today is discussed controversially in the professional world, it is undoubtedly one of Europe’s most remarkable Neolithic sacred monuments.

While the area around Newgrange and the no less significant monuments of Knowth and Dowth north of the Boyne belong to the World Heritage Site of the Brú na Bóínne, the areas south of the Boyne are only partially recorded and documented archaeologically. Standing in the local landscape today, it is still obvious that the individual monuments refer to each other spatially and are located on hills that form a visual axis. This year our team from the Unit for Survey and Excavation Methodology conducted a magnetic survey in the southern periphery of the World Heritage Site. We started on Donore Hill – a hill site in line with the monuments mentioned before.

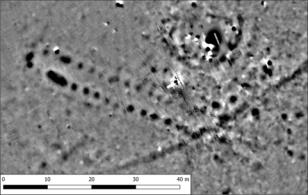

Here, current property owners pointed out a cairn, popularly referred to as the „famine grave“, located at the highest point of the area. On the basis of the name, it is generally assumed that it is a modern grave dating to the great famine of 1845-1849. Our magnetic survey of the area shows posthole structures and ditches similar to the Neolithic monuments at the heart of the Boyne Valley World Heritage site. In the immediate vicinity clear posthole structures of a large longhouse are visible. We therefore suspect that this actually is a Bronze Age building (Fig. 4).

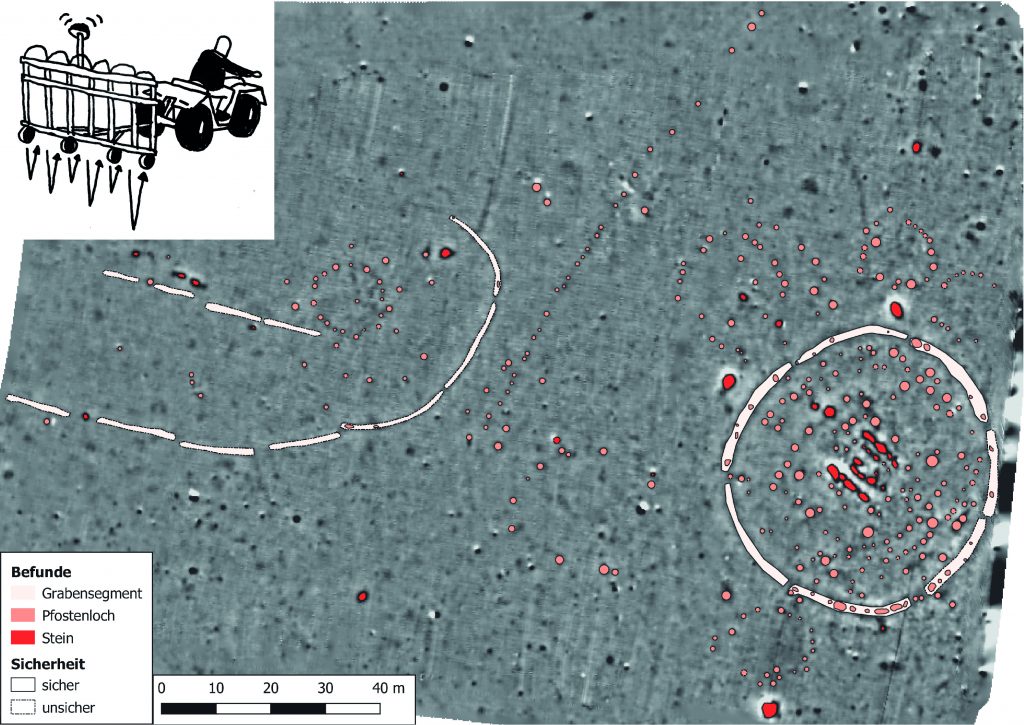

In 2018, we came across a Neolithic monument of circular tombs, posts, and possibly stone structures not far from Newgrange. This year we were able to complete our survey of this area (Figure 3, red area A). The evaluation and interpretation of these structures in view of the new data is still ongoing. This process can be followed in Figure 5, which shows a possible interpretation of anomalies based on nT values, shape and size.

The Boyne Valley is still one of the most fertile areas of Ireland. Its rich and diverse landscape is certainly one of the reasons why so many traces of intense human activity can be found here that date back all the way to Neolithic. On the other hand, it is all the more astonishing that similarly intensive construction activities can be documented on the more remote Orkney Islands of Scotland, too.

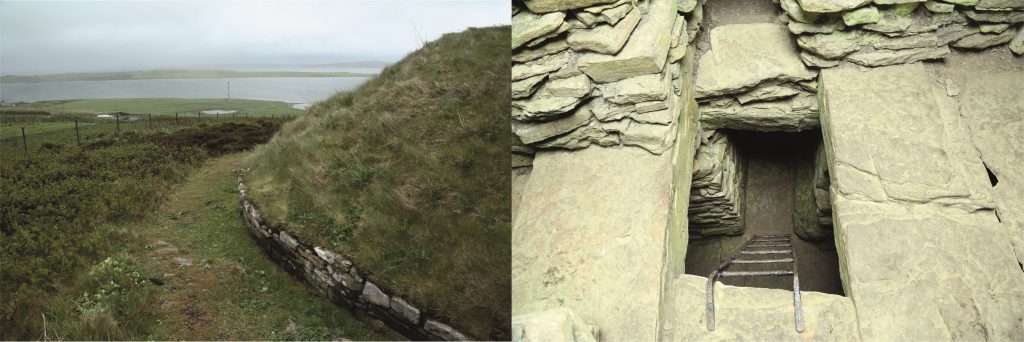

Only a small part of the island of Rousay can be used for agriculture. As such it seems hardly surprising that few Neolithic settlements are found here. In stark contrast, however, numerous megalithic tombs have been documented here: monumental tombs with one or more corridor and chamber systems. The Taversoe Tuick on Rousay is very special (Fig. 6): Here the chambers are actually spread across two levels.

In the Boyne Valley in Eastern Ireland and on Orkney in Scotland’s north, the World Heritage sites extend beyond the extraordinary monuments themselves and include their archaeological hinterland. Consequently, the research of the RGK and our Irish and Scottish partners focuses on large areas in these landscapes, in order to place these monuments in a wide archaeological context.

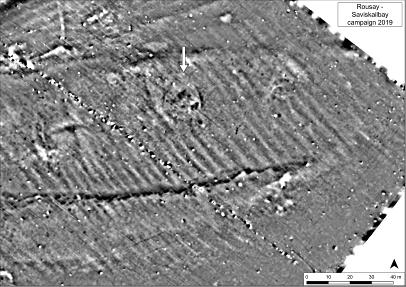

As part of our project, we investigate the relationship between settlements and (grave) monuments. In the case of Rousay, we must now ask ourselves whether it is only owed to the current state of research that grave monuments dominate the finds from the Neolithic period or whether the island was used primarily as a place for the dead. With our vehicle-based 14-sensor system (Fig. 2), we are able to magnetically survey very large areas and hereby document the surroundings of the well-known monuments. Using this approach we have been able to identify settlement remains in the Rinyo Valley (Fig. 1, in eastern Rousay) that are similar to those of the famous site of Skara Brae on the island of Mainland (Fig. 1).

During the 2019 season, we concentrated on a large area around Loch Wasbister (Fig. 1 and 7) and came across lightning strikes and old field systems in several places. But we were also able to identify structures that are probably traces of Neolithic or Bronze Age monuments whose remains are no longer visible on the surface (see Fig. 8).

Last but not least, we were rewarded with good weather and even sunshine (Figure 9) on our last day of this year’s campaign on Rousay.

Our heartfelt thanks go to our Scottish and Irish colleagues for the excellent cooperation!

Mòran taing and go raibh maith agat!