Antique remains used to be documented through drawings and engravings or with gypsum casts and models even before archaeology became an established scientific occupation. These products of artists and travellers, although sometimes blended with fantasy, were the primary visual source of information until photography was introduced and applied in archaeology. These early documents are sources of information that we still use today despite all the errors they may contain.

One of the basic methodological challenges of archaeology has always been the objectivity of documentation. The ”Description de l’Égypte” from 1809, a series of volumes which were published after Napoleon’s campaign to Egypt from 1798-1801 was the first source in which antique remains were illustrated according to their actual scales. This is one of the first expressions of European positivism in archaeology (E. Eldem, Z. Çelik, Z. Bahrani, Scramble for the Past: a story of archaeology in the Ottoman Empire (Karaköy 2011); B. Forster, Belichtete Vergangenheit. Archäologie und Fotografie (Marburg 2017)).

The second half of the 19th century was the beginning of photography in archaeology. With both the scientific development of archaeology and the development of photographic technologies, photography replaced these early paintings and engravings. Documenting findings and excavations precisely and objectively became significant in archaeology; because archaeologists were aware that removing the earth which covers the ancient remains meant destroying the layers while digging. As part of this process, photography turned out to be a ”lifesaver”. But still, the transition from drawings to photography was gradual. Thus it was customary for example to use the single images which have been taken with the first photographic printing method, the Daguerreotypie as masters for reproductions by painters and engravers. Additionally, taking photographs of the archaeological sites was not an easy task. The early photographers had to carry heavy cameras, sturdy tripods, big format (glass) negatives, and sometimes even darkroom chemicals to the field.

After 1850, it was possible to obtain hundreds of photo prints from a single negative. With the possibility of mass reproduction of photography, the usage of photographs spread widely. However, the area of utilization was still limited due to high costs, and the complicated printing process for high-quality results. Not each excavation project could afford to have a photographer and a fully equipped photo laboratory. Alexander Conze’s report of the Samothrace excavations (1880) was one of the first publications which included archaeological photographs (A. Conze, Archaeologische Untersuchungen auf Samothrake. Ausgeführt im Auftrage des K. K. Ministeriums für Kultus und Unterricht, mit Unterstützung Seiner Majestät Corvette “Zrinyi” Commandant Lang (Wien 1880)). In the following years, photography became one of the most significant elements in archaeological research due to methodological and technical developments. The fact that cameras became lighter, the availability of film material became easier, the number of necessary darkroom materials decreased, their capabilities increased, and eventually, enabled photography to take a more and more important role in archaeology. To work as an excavation photographer in the field became the rule, not an exception. However, over time more and more archaeologists became self-taught photographers. One of the biggest changes came about twenty years ago with the introduction of digital photography. Digital photography did not require any longer a lab to develop the material and the image. The pictures could be checked for their sharpness, contrast and motive directly after pressing the shutter. With the digitalization of photography, analogue cameras, photographic films, certain kinds of camera flashes, and dark room equipment became obsolete and disappeared almost completely.

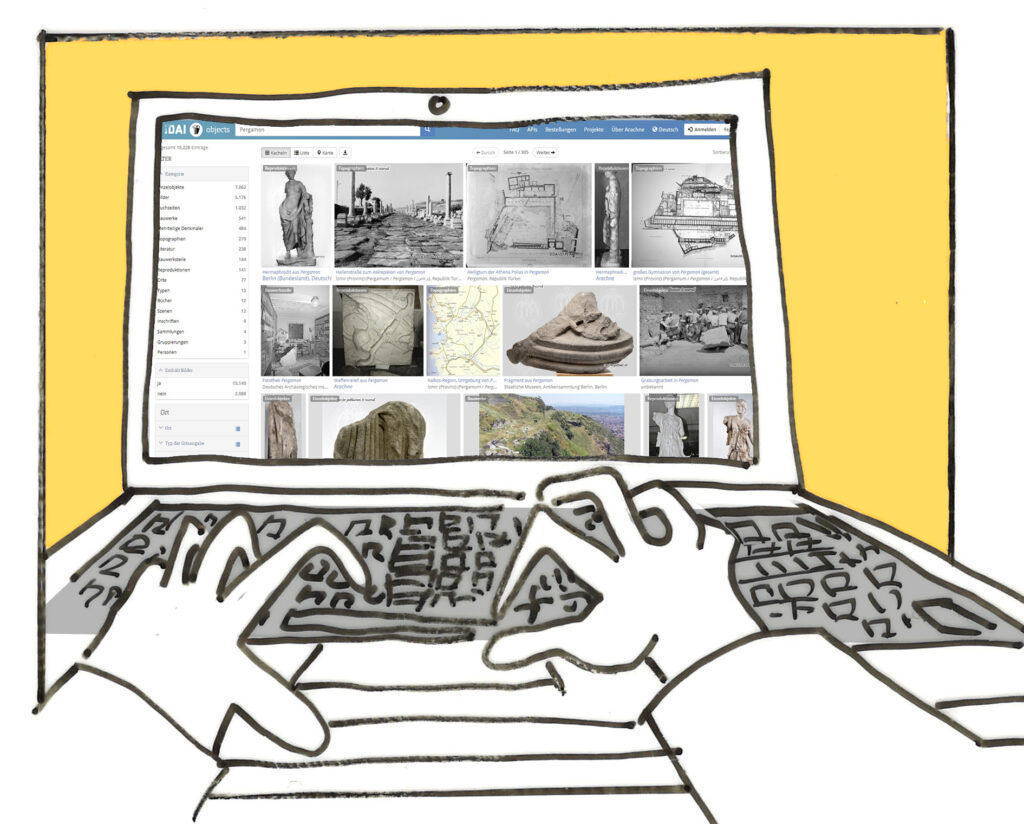

Through the “digital turn” taking photos became the predominant method for documenting finds and findings, recording all steps of excavations or surveys. Photography is an inevitable part of archaeological projects and takes place in almost every aspect of an archaeological study. Today, it is not only an “objective tool, but as well as a powerful medium of public outreach and visualization of archaeological research and fieldwork” (A. Busching, Ausgegraben: Aus den Fotosammlungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts = Historical pictures from the archives of the German Archaeological Institute (Berlin 2015)). Photos combined with sketches and the field diary entries allow archaeologist to continue their archaeological studies off-field, e.g. at libraries and offices for months or years even after the actual excavations have been completed.

Digital photographs in interaction with computing techniques to process multiple photographs have opened up other possibilities for documentation. With the help of Structure from Motion software photographs can be processed into three-dimensional point clouds and further processed into three-dimensional models. It was always a challenge to take aerial photographs for overview images of archaeological sites and the surrounding areas. Cameras were mounted on balloons, kites, or long poles; others built high towers with scaffolding or hired a helicopter to take overview images. Nowadays, archaeological sites are fairly easily documented with aerial photos taken with drones.

Although photography is nowadays an indispensable component of archaeology, the future of professional archaeological photography is uncertain. It is a matter of expertise and experience to be able to take (accurate) archaeological photographs with all technical requirements considered. Especially experience and expertise are required to set and use appropriate lighting conditions in the field, to document tiny details with precision. This kind of knowledge is also important to adjust artificial lighting to take tailor-made photographs of small finds in laboratories, depots and offices. Trained archaeological photographers cover this technical expertise (A. Özener, Arkeoloji Biliminde Fotoğraf Teknikleri (Çanakkale University Master Thesis 2015)). They are capable to find a perfect point of view and to set the right light in order to reflect the multi-layered structure of the excavation or building exposed. If inappropriate lighting and materials are used for archaeological photography results may not match with the expected outcome. Thus, archaeological photographers should have the (“excavation”) background and experience to reflect the style, scale, colour and texture properly on the photographs. There is a need to find the right balance between a technical perfect representation of a motive to be published later, the arrangement that may makes it a beautiful picture to reach out, and the objectivity of the “photo-documentation” of a certain find context. Yet this technical experience should also be complemented with a good knowledge of the excavation site and the particular period, as well as a solid familiarity with archaeological practices and objects.

Nevertheless, archaeological photographers will for sure not disappear because of digital technologies, but their role may change. Instead of developing photos in a darkroom they are now sitting in front of a computer screen and use the digital photo-lab-software to produce best possible results. Time will tell, what comes next, but for sure photography will be a part of it.

Photography has played in many ways an innovative role for the science of archaeology. It has, however, an ongoing mission too; the photos and the technology behind have turned into archival material itself. Every excavation project brings home an archive and these archives, in turn, play an important role in expanding archaeological research by being first hand, primary (digital) data. When the photographs are taken, whether in the field, at the excavation house or at a museum etc. all information required, e.g. location, trench, locus, object, direction, date, and the photographer’s name, is noted down in a photo list, diary or database. This is required to archive them properly according to current guidelines, standards, and FAIR principles (Findability, Accessibility, Interoperability, and Reuse) to locate and make use of them afterward. With digital photography the amount of photos to be archived increased substantially, which creates new challenges for photo archives. Although photography in archaeology is now almost exclusively digital, the historic analogue photographs in our archives may continue to contribute to current and future scientific discussions.

Historic photographs can visualise the impact of environmental changes over time, or enables us to revisit places to gain an idea of how a site or building actually looked like when the photo was taken. In addition, those photographs can inform us about excavation techniques and methods applied or events that took place in and around archaeological sites. Moreover, photo archives offer as well insights into the lives of often-overlooked excavation workmen or in general people in a certain context and time.

Unfortunately, we do not know the names of many archaeological photographers who contributed to the archives. In particular, in earlier times, the names of the excavation photographers are (often) not mentioned in the archaeological records and publications for which the photographs were taken. The value of the photographs was primarily to have and keep them in the archives and not in the first place to acknowledge who may have produced them; this has for whatever reasons always been a fairly common practice. However, this approach has changed radically due to copyright and use-right regulations; all to ensure that the images kept in the archive can be found and re-used also in the future.

Author: Berna Güler

DAI Istanbul, Photo Archive

Further Reading:

Âsâr-ı Atika Nizamnâmesi, İstanbul: Asır Matbaası, 1322(1906)

Bahrani Z., Ҫelik Z., Eldem E., Scramble for the past: a story of archaeology in the Ottoman Empire, 1753-1914, Istanbul: Salt, 2011

Ҫelik Z., Gür A., About antiquities: politics of archaeology in the Ottoman Empire, Austin: University of Texas Press, 2016

Ҫelik Z., Eldem E., Eagle H., Camera Ottomana: photography and modernity in the Ottoman Empire, 1840-1914, Istanbul: Koç University, 2015

Forster B., Belichtete Vergangenheit. Archäologie und Fotografie (Marburg 2017)

Köşker B., Arkeolojide Fotoğraf, Marmara University, Master Thesis Istanbul: 2002

Özendes E., Osmanlı İmparatorluğu’nda fotoğrafçılık: 1839-1923, Istanbul: Yem Publicationhause, 2013

Özendes E., Türkiye’de fotoğraf = Photography in Turkey, İstanbul: Türkiye Ekonomik ve Toplumsal Tarih Vakfı ; Pamukbank, 1999

Özener A., Arkeoloji Biliminde Fotoğraf Teknikleri, Ҫanakkale Onsekiz Mart University, Master Thesis, 2006

Öztuncay B., Robertson: Osmanlı başkentinde fotoğrafçı ve hakkâk = photographer and engraver in the Ottoman capital, İstanbul: Vehbi Koç Foundation, 2013

Öztuncay B., Ertem Ö., Tarihin merkezine seyahat: Fotoğraf ve Osmanlı köklerinin yeniden keşfi (1886), Istanbul: Koç University, 2018

Sontag S., On Photography, New York: Picador, 2001