Islamic law schools in northern Africa. Order of architecture and law

Starting the 12th century CE, law schools were founded across much of northern Africa. The starting point of this development lies in the Middle East. The first madrasa in Cairo was established by Saladin in 1171. Foundations followed in Tunis (1238), Fes (1271), and Granada (1349). Through these foundations, rulers intended to foster a moderate, socially acceptable Islam as a response to the reform movements of the forgoing centuries – in the East the Shiism of the Fatimids, in the West the radical Zahiri school of the Almohads. At the same time, the patrons were attempting to keep the increasing tendencies towards Sufism, a mystic movement that was gaining widespread support among the local population, under control.

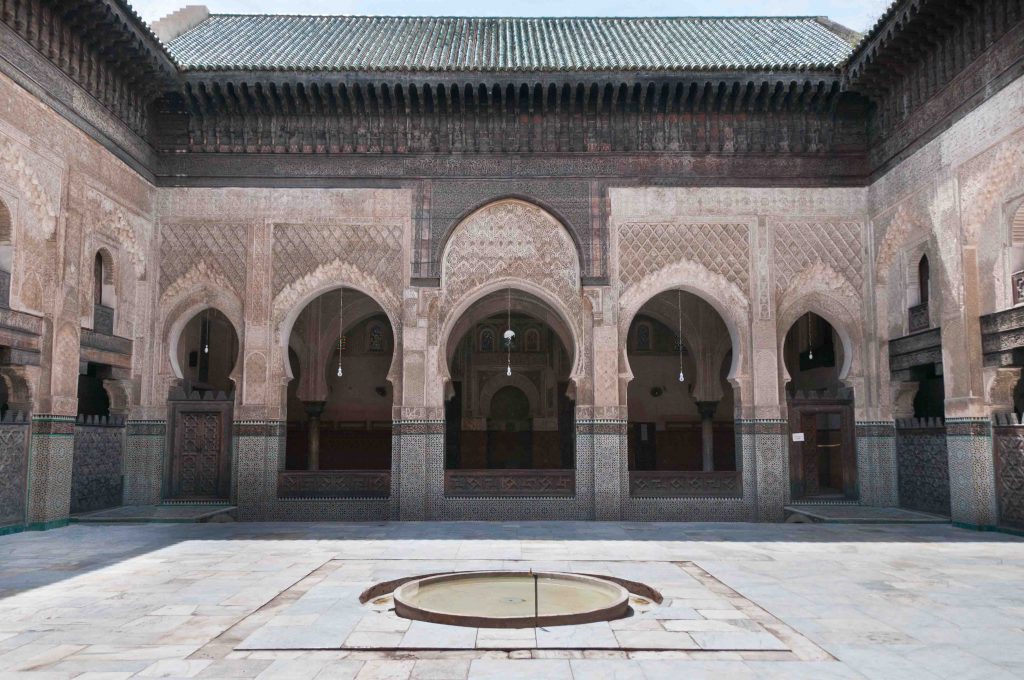

In northern Africa, more than 30 madrasas of the 13th and 14th century are preserved, among them such famous buildings as the madrasa of Sultan Hasan in Cairo and the madrasa Bou Inania in Fes. The aim of a new project initiated by the German Archaeological Institute in Madrid is to document these buildings, elaborate reliable architectural plans, and analyze their architectural design.

In analogy to the schools of thought that were taught at the madrasas, the architectural design of the buildings can be viewed as a normative act. Even more than other types of Islamic architecture – like mosques and palaces – the madrasa buildings are the result of the application of logic and geometry to the organization of space. The comparison between the design process in architecture and the logic applied to jurisprudence provides new insights into the crisis of reason of the 13th and 14th century, and thus into a conflict that remains virulent in northern Africa even today.

The development across Africa was by no means uniform. The style of architecture was as different as the schools that were fostered in the madrasas – mainly the Maliki School in the West and the Shafi’i and Hanafi schools in the East. Typological differences – broad halls in the West, iwans in the East – are evident and have been described at several occasions. Less evident are differences in the geometrical principals that were applied in the design of the buildings. In the West, the equilateral triangle played an important role, for example, while in the East, the properties of the octagon were more important for the design of building plans. The madrasas are thus not only an example for the congruence of cultural developments across northern Africa but also for the differences that have shaped this wide region.

Members

Felix Arnold

DAI Madrid

felix.Arnold@dainst.de