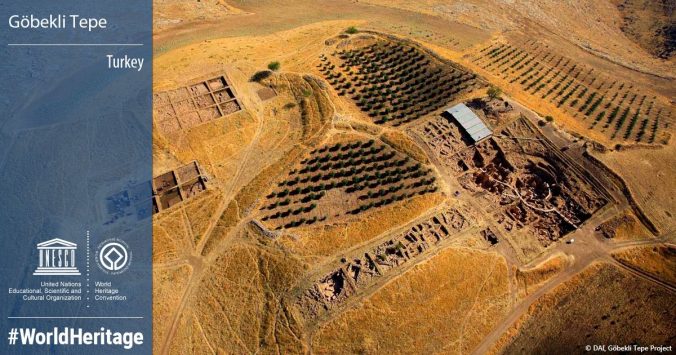

Well, the short answer would be: Stone Age people with Stone Age tools. Nothing more needed, no aliens, no giants, as you can read here. For an answer to the question, who these Stone Age people were, where they came from and lived (Göbekli Tepe is not a settlement), we will have to make the finds speak.

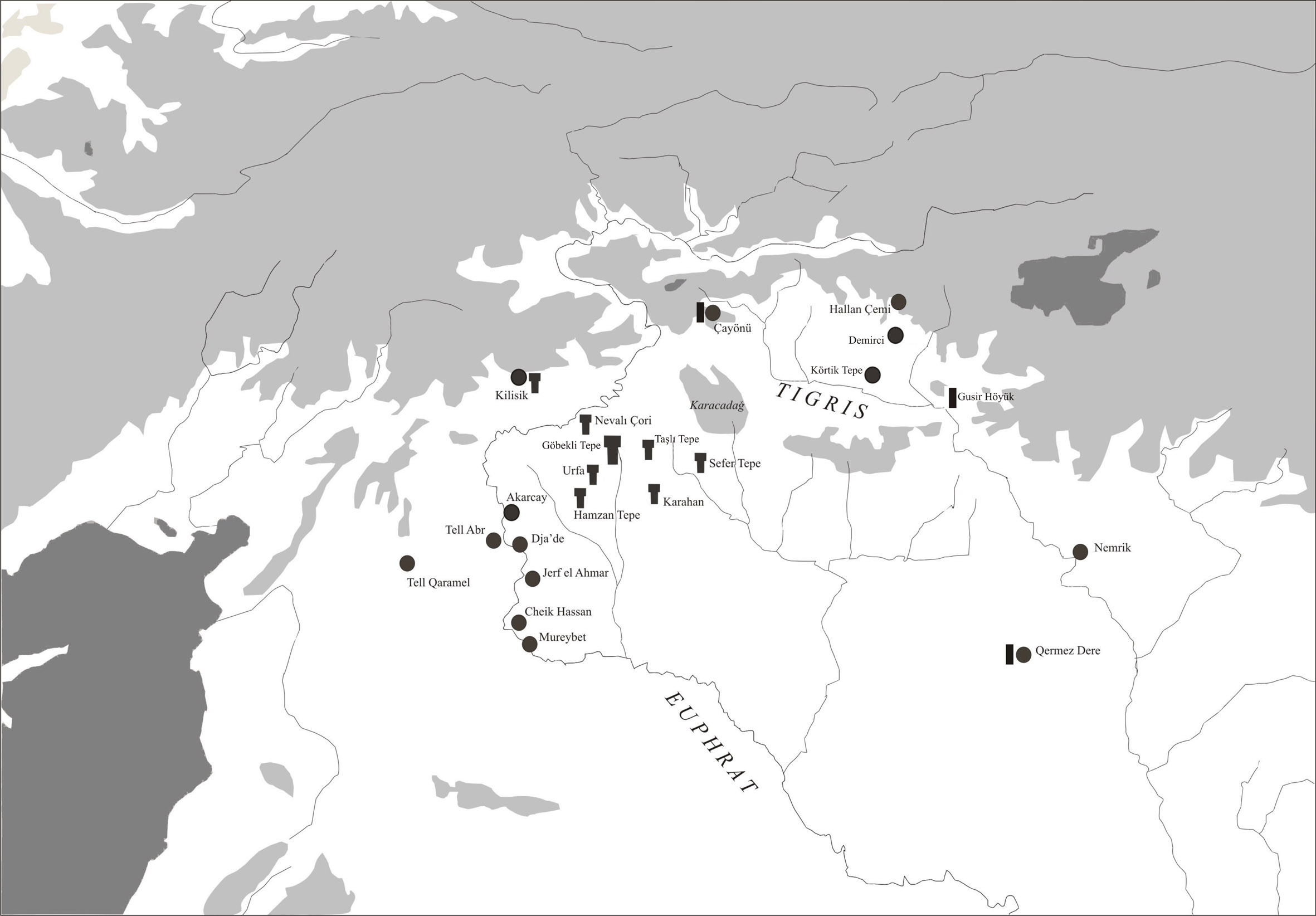

A point to start is the distribution of sites with similar architecture. Göbekli Tepe is not the only site with T-shaped pillars. Similar sites concentrate roughly between the Upper Balikh and the Upper Chabur rivers [read more here]. They clearly mark a region with similar cultural traits. However, the area the builders of Göbekli Tepe came from exceeds this region by far.

Gusir Höyük (Karul 2011, 2013) in the Turkish Tigris region has considerably widened the distribution area of circular enclosures. However, the pillars discovered there are slightly different, they miss the T-bar. Similar stelae have been discovered in Çayönu (Özdoğan 2011) and in Qermez Dere (Watkins et al. 1995). In addition to these two different architectonic regions, to the west, in northern Syria, a third distinct building style can be pointed out. Domestic sites like like Jerf el Ahmar, Mureybet or Tell ´Abr 3 (Stordeur et al. 2000; Yartah 2013) also have circular communal buildings. These are constructions with pisé walls and wooden supports however. Upper Mesopotamia can thus be differentiated by building traditions. But the common element is the existence of similarly arranged communal buildings, and, more important, of a range of common symbols.

Distribution of Göbekli Tepe´s iconography and of wild wheats (Map: T. Götzelt, Copyright DAI).

For example, shaft straighteners and plaquettes from Jerf el Ahmar (Stordeur & Abbès 2002) and Tell Qaramel (Mazurowski & Kanjou 2012), as well as Tell ´Abr 3 (Yartah 2013), and Körtik Tepe (Özkaya & Coşkun 2011) feature decorations in the form of snakes and scorpions, quadruped animals, insects, and birds strongly reminiscent of the iconography of Göbekli Tepe, where they appear not only on the pillars, but also on similar items.

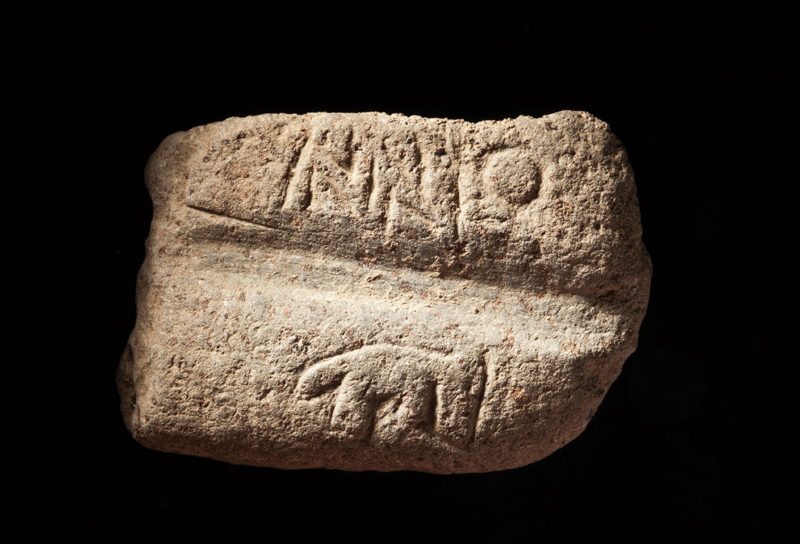

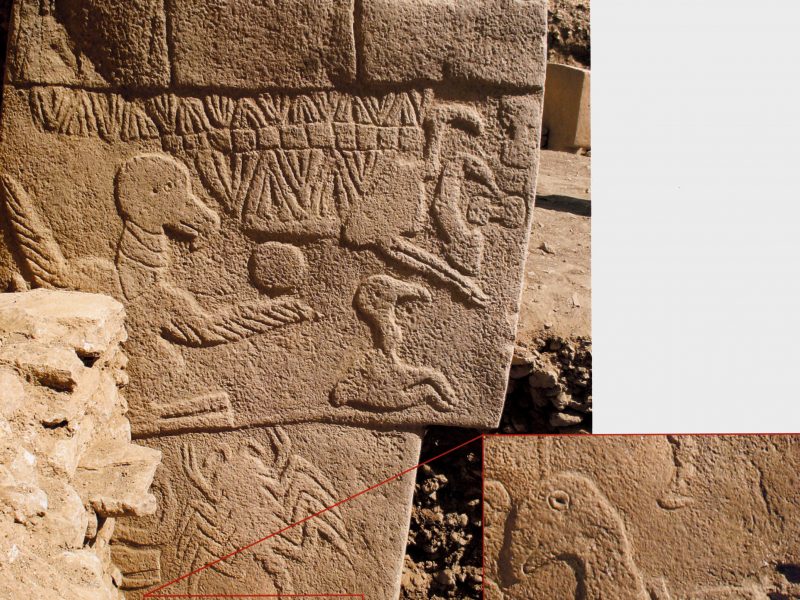

Plaquette with depiction of a snake, a human (?) and a bird (Photo Irmgard Wagner, Copyright DAI).

Most striking in this regard is a small plaquette from Göbekli Tepe. From the left to the right, it shows a snake moving upwards, a stylized human figure (?) with raised arms, and a bird. What makes this small find so interesting, is that the combination of depictions reappears not only in similar (e.g. in Jerf el Ahmar with a fox in place of the human-shape?), but also in completely and nearly identical form twice on another site, Tell Abr´3 in northern Syria (Köksal-Schmidt & Schmidt 2007; Yartah 2013, with images [external link]).

- Fragment of a decorated stone bowl from Göbekli Tepe (Photo N. Becker, Copyright DAI).

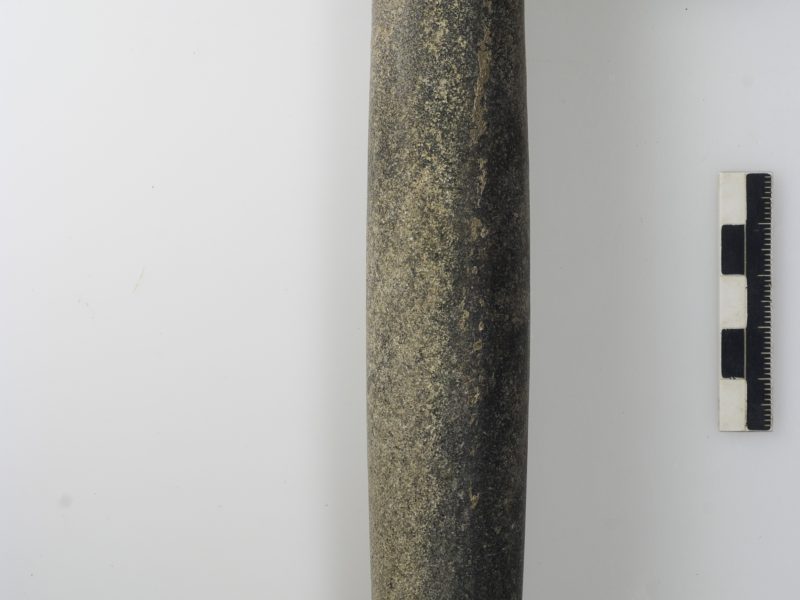

- “Sceptre”, type Nemrik, from Göbekli Tepe (Photo Nico Becker, Copyright DAI).

- Fragment of a decorated stone bowl from Göbekli Tepe (Photo. Schmidt, Copyright DAI).

- Decorated shaft straigthener from Göbekli Tepe (Photo N. Becker, Copyright DAI).

The same range of depictions of snakes, scorpions, quadrupeds, insects, and birds occurs on thin walled stone cups and bowls of the Hallan Çemi type (Rosenberg & Redding 2000). Fragments of this vessel type are known from Göbekli Tepe, Çayönü (Özdoğan 2011), Nevalı Çori, Jerf el Ahmar (Stordeur & Abbès 2002), Tell ´Abr 3 (Yartah 2013), and Tell Qaramel (Mazurowski & Kanjou 2012), while complete vessels have been discovered at Körtik Tepe in large numbers (Özkaya & Coşkun 2011) as part of rich grave inventories. Another connection is suggested by the zoomorphic scepters of the Nemrik type, which are present at Hallan Çemi, Nevalı Çori, Çayönü, Göbekli Tepe, Abu Hureyra, Mureybet, Jerf el Ahmar, and Dja´de (Kozłowski 2002).

We thus see a large area in Upper Mesopotamia connected by a similar iconography. While, as detailed above, several domestic sites show some aspects of this world, it concentrates at non-domestic Göbekli Tepe.

El-Khiam-, Helwan-, Nemrik- and Byblos-Points from Göbekli Tepe (Photo Irmgard Wagner, Copyright DAI).

The range of flint projectile points made on-site may further strengthen the impression of people from different areas gathering here (Schmidt 2001). PPN A types present at Göbekli Tepe include el-Khiam, Helwan and Aswad points; regarding the PPNB, Byblos and Nemrik points are very frequent, Nevalı Çori points are rare. Nemrik points have an eastern distribution pattern within the fertile crescent, el-Khiam and Byblos points are distributed to the west, within the Levant, Nevalı Çori points more to the north and the middle Euphrates area (Kozłowski 1999). It has to be stressed here that those points were not imported-the flint used is clearly local. At Göbekli Tepe, the whole reduction sequence is attested, although flint is not present at the limestone plateau, but had to be brought to the site from the surrounding valleys. Most of the primary production is based on naviform cores. Flint knapping took place in an abundance not known from contemporaneous sites. Maybe some characteristic of the place made it especially desirable to use points made there. Another possible point in favor of people from a larger area congregating at Göbekli Tepe is presented by raw material sourcing of the obsidian found onsite [read more here – external link].

So, to finally answer the question of who built Göbekli Tepe: Stone Age people coming from a radius of roughly 200km around the site. With Stone Age tools.

References

- Karul, N. (2011). Gusir Höyük. In: Özdoğan, M., Başgelen, N. & Kuniholm, P. (eds), The Neolithic in Turkey 1. The Tigris Basin. Archaeology & Art Publications, Istanbul 1-17.

- Karul, N. (2013). Gusir Höyük/Siirt. Yerleşik Avcılar. Arkeo Atlas 8, 22–29.

- Kozłowski, S.K. (1999). The eastern wing of the Fertile Crescent. Late prehistory of Greater Mesopotamian lithic industries. Oxford: Archaeopress.

- Kozłowski, S. K. (2002). Nemrik. An aceramic village in northern Irak. Warsaw: Institute of Archaeology Warsaw University.

- Mazurowski, R.F., Kanjou, Y. (eds., 2012). Tell Qaramel 1999–2007. Protoneolithic and Early Pre-pottery Neolithic Settlement in Northern Syria. Warsaw: Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology.

- Özdoğan, A. (2011). Çayönü. In: M. Özdoğan, N. Başgelen & P. Kuniholm (eds.), The Neolithic in Turkey 1. The Tigris Basin. Istanbul: Archaeology and Art Publications, 185-269.

- Özkaya, V. & Coşkun, A. (2011). Körtik Tepe. In: M. Özdoğan, N. Başgelen & P. Kuniholm (eds.), The Neolithic in Turkey 1. The Tigris Basin. Istanbul: Archaeology and Art Publications, 89-127.

- Rosenberg, M. & Redding, R.W. (2000). Hallan Çemi and early village organization in Eastern Anatolia, in Kuijt, I. (ed.), Life in neolithic faming communities. Social organization, identity and differenziation. New York et. al.: Kluwer Academic / Plenum Publishers, 39-61.

- Schmidt, K. (2001). Göbekli Tepe, Southeastern Turkey. A Preliminary Report on the 1995-1999 Excavations. Paléorient 26/1, 45-54.

- Stordeur D. & Abbès. F. (2002). Du PPNA au PPNB: mise en lumière d’une phase de transition à Jerf el Ahmar (Syrie). Bulletin de la Société Préhistorique Française, 99(3), 563-595.

- Stordeur, D., Brenet, M., Der Aprahamian, G. & Roux, J.-C. (2000). Les bâtiments communautaires de Jerf el Ahmar et Mureybet horizon PPNA (Syrie). Paléorient 26, 1, 29-44.

- Watkins, T., Betts, A., Dobney, K. & Nesbitt. M. (1995). Qermez Dere, Tel Afar, north Iraq: third interim report, in T. Watkins (ed.) Qermez Dere, Tel Afar, north Iraq: interim report no 3. Edinburgh: Department of Archaeology, University of Edinburgh, 1–9.

- Yartah, T. (2013). Vie quotidienne, vie communautaire et symbolique à Tell´Abr 3 – Syrie du Nord. Données nouvelles et nouvelles réflexions sur L´horizon PPNA au nord du Levant 10000-9000 BP. Unpublished PhD Thesis, Lyon.

Further Reading (links to fulltexts)

- Dietrich, O., Heun, M., Notroff, J., Schmidt, K. & Zarnkow, M. (2012). The Role of Cult and Feasting in the Emergence of Neolithic Communities. New Evidence from Göbekli Tepe, South-eastern Turkey. Antiquity 86, 674-695.

- Köksal-Schmidt, Ç & Schmidt, K. (2007). Perlen, Steingefäße, Zeichentäfelchen. Handwerkliche Spezialisierung und steinzeitliches Symbolsystem. In: Badisches Landesmuseum Karlsruhe (ed.), Vor 12000 Jahren in Anatolien. Die ältesten Monumente der Menschheit, Stuttgart, 97-109.

- Schmidt, K. (2005). “Ritual Centres” and the Neolithisation of Upper Mesopotamia. Neo-Lithics 2/05, 13-21.

Recent Comments