Just back from this year´s ICAANE in Vienna, where a very inspiring workshop on the “Iconography and Symbolic Meaning of the Human in Near Eastern Prehistory” was organized by Jörg Becker, Claudia Beuger and Bernd Müller-Neuhof. As publication of the contributions will take some time, here is a small summary of our musings on anthropomorphic imagery at Göbekli Tepe.

Göbekli Tepe is a special site in many respects: its location is hostile to settlement, no water sources are in vicinity; clear evidence for domestic building types missing so far in Layer III; only selection of material culture is present (very few bone tools, clay figurines absent); and there is a considerable investment of resources and work. This investment was not only made in building Göbekli Tepe. At the end of their uselifes, all buildings of layer III (PPN A, 10th millennium) were at least partially intentionally backfilled. The filling consists of limestone rubble from the neolithic quarry areas on the adjacent plateaus, mixed with large quantities of animal bones, flint debitage, artefacts and tools. Before backfilling started, it seems that the buildings were cleaned. If roofs should have existed, they were dismantled at that time, because absolutely no traces of them were found.

The backfilling obviously is a limiting factor for our understanding of the function of the enclosures, as very few in situ deposits connected to the use-time of the buildings remain. However, it seems that the backfilling was a very structured process that included certain deliberate acts. Between them, the deposition of artefacts and sculptures [here, here, here, and here] inside the filling, often next to the pillars, is most striking.

Deposition of a boar sculpture an stone plates next to one of the central npillars of Enclosure C (Photo: K. Schmidt, Copyright DAI).

So, at Göbekli Tepe we do not know very much about the actual usetime of the buildings. We have however the enclosures themselves, their layout, and the richly decorated pillars as starting points. And we know a lot of the things people did with these enclosures at the end of their uselife. It seems that they tried to highlight certain aspects of the enclosures´ meaning through their actions.

Western central pillar of Enclosure D (Photo: N. Becker, Copyright DAI).

There are several different categories of human imagery at Göbekli Tepe. Most impressive are the T-shaped pillars. The T-shape is clearly an abstract depiction of the human body seen from the side. Evidence for this interpretation are the low relief depictions of arms, hands and items of clothing like belts and loinclothes on some of the central pillars. There is a clear hierarchy of pillars inside the enclosures. The central pillars are up to 5,5 m high, they have the already described anthropomorphic elements. The surrounding pillars are smaller, but more richly decorated with animal reliefs than the central ones. They are always „looking“ towards the central pillars, and the benches between them further amplify the impression of a gathering of some sort. Whether we are dealing with depictions of ancestors of different importance, or even of gods, would be a topic for itself and an answer is hard to find at the moment.

What is clear however is that both central and surrounding pillars share the abstracted form. This abstraction is not due to the limited skills of Neolithic people in depicting the human body. It is a deliberate choice that has a meaning.

Anthropomorphic sculpture; torso and head, limestone. The only case in which fitting fragments of an anthropomorphic sculpture were found at Göbekli Tepe (Photo: N. Becker, Copyright DAI).

The other important category of depictions are more naturalistic sculptures. A total of 143 sculptures was found so far at Göbekli Tepe. Of those, 84 depict animals, 43 humans, 3 phalli and 5 are human-animal composite sculptures. It is striking that most anthropomorphic sculpture at Göbekli Tepe is fragmented. Of the 43 human-shaped depictions, only 9 can be regarded as complete, if we do not take smaller damages into account. What is also striking is that – in spite of large-scale excavations – there is only one case in which fitting fragments were found. If we have a closer look at the fragments preserved, a pattern emerges. The fragments preserved in the highest numbers are heads, not the often bigger torsi. The large number of broken off heads, and the regulated fractures, speak in favor of intentional fragmentation.

A selection of anthropomorphic heads from Göbekli Tepe (Photos: DAI).

Further, the heads were not discarded randomly. They were deposited carefully in the enclosure fillings, often next to pillars. Their treatment is similar to zoomorphic sculpture in this respect. However, zoomorphic depictions are most often complete, there is no indication of intentional damage. So while deposition patterns are similar, pre-deposition treatment is not. Human heads seem to have had a special role in the beliefs connected with the enclosures.

Distribution of sculptures in the main excavation area of Göbekli Tepe (Map: Thomas Götzelt, Graphics N. Becker, Copyright DAI).

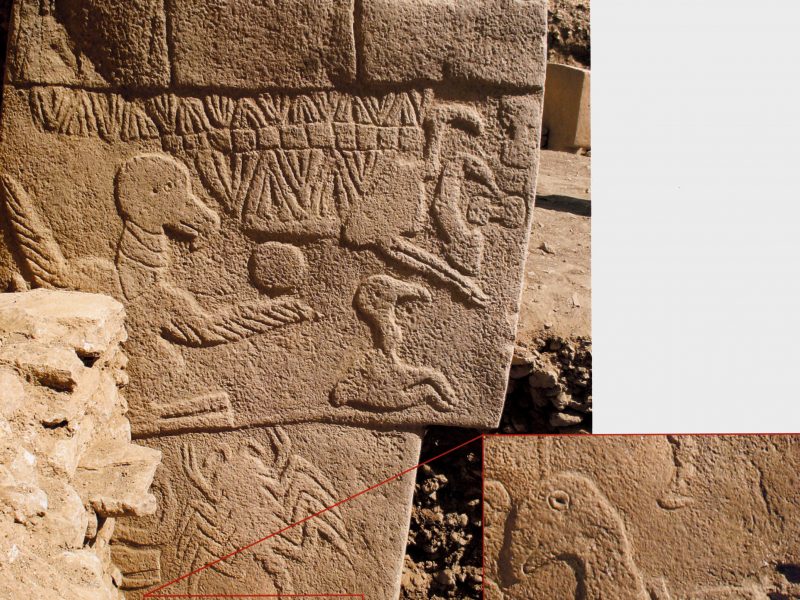

The special role of separated human heads is also visible in Göbekli Tepe´s reliefs. Immediately behind the eastern central pillar of Enclosure D the fragment of a relief was found. It shows a human head among several animals – a vulture and a hyena can be clearly identified. Another example is Pillar 43, also in Enclosure D. There, a headless ithyphallic body is depicted among several birds, snakes and a large scorpion. The interaction of animals with human heads is even clearer from several composite sculptures discovered at Göbekli Tepe. They show birds, but also quadrupeds sitting on top of human heads or carrying them away. A relation of this kind of iconography with early Neolithic death rite and cult is evident.

- Fragment of a relief showing a separated human head among animals. Found next to one of the central pillars of Enclosure D (Photos N. Becker, Copyright DAI).

- Pillar 43 in Enclosure D with a depiction of a headless man (Photo K. Schmidt, Copyright DAI).

The special treatment and the removal of skulls is well-attested for the PPN. One of the most remarkable examples is the skull building from Cayönü. At this site, the situation is very much opposed to Göbekli Tepe however. There are lots of burials, but only a few anthropomorphic depictions. At Nevali Cori, burials with separated skulls, in one case with a flint dagger still in place, were discovered, but also an imagery that is very similar to Göbekli Tepe. For example, the so-called totempole shows a bird sitting on a human head. There is also a larger number of limestone heads from Nevali Cori, mirroring the situation at Göbekli Tepe to some degree. Of course, one could also add the special treatment of human heads in many southern Levantine sites, but also at Köşk Höyük and Catalhöyük here. At Catalhöyük, we find many of the elements observable at Göbekli Tepe still in place in a much later context. This includes iconography of birds carrying away human heads, special treatment of heads in burials and figurines with intentionally broken off heads, or with heads designed from the start to be taken off.

To sum up, at Göbekli Tepe there is evidence of a hierarchy of anthropomorphic depictions. The central pillars of the enclosures are abstracted and clearly characterized as anthropomorphic by arms hands, and items of clothing. The surrounding pillars are also abstracted, but smaller, and show mainly zoomorphic decorations. They are looking towards the central pillars and evoke the association of a gathering.

Naturalistic anthropomorphic sculpture is smaller and intentionally fragmented. During backfilling of the enclosures, a selection of fragments, mostly heads, was placed inside the filling, most often near the central pillars. This practise is highly evocative of elements of neolithic death cult that also reflects in Göbekli´s iconography.

It seems that the abstracted pillar-beings represent another sphere than the naturalistic sculptures. Zoomorphic and anthropomorphic sculpture is placed next to them. The connection to death rites could indicate that the pillars belong to that sphere. Whether we are dealing with depictions of important ancestors here, and whether the deposition practice of fragmented sculpture, and, during the use-time of the enclosures, possibly human heads- vizualizes that new members are added to this group, remains a question for further studies.

Further reading:

Nico Becker, Oliver Dietrich, Thomas Götzelt, Cigdem Köksal-Schmidt, Jens Notroff, Klaus Schmidt, Materialien zur Deutung der zentralen Pfeilerpaare des Göbekli Tepe und weiterer Orte des obermesopotamischen Frühneolithikums, ZORA 5, 2012, 14-43.

Jens Notroff, Oliver Dietrich, Klaus Schmidt, Gathering of the Dead? The Early Neolithic sanctuaries of Göbekli Tepe, Southeastern Turkey, in: Colin Renfrew, Michael Boyd and Iain Morley (Hrsg.), Death shall have no Dominion: The Archaeology of Mortality and Immortality – A Worldwide Perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (2016), 65-81.

On Çayönü:

Özdoğan, Mehmet and Aslı Özdoğan .1989. „Çayönü. A Conspectus of recent work.“ Paléorient 15: 65-74.

Özdoğan, Mehmet and Aslı Özdoğan .1998. „Buildings of cult and the cult of buildings.“ In Light on top of the Black Hill. Studies presented to Halet Çambel, edited by Güven Arsebük, Machteld J. Mellink and Wulf Schirmer, 581-601. Istanbul: Ege Yayınları.

Özdoğan, Aslı. 2011. “Çayönü.” In The Neolithic in Turkey 1. The Tigris Basin, edited by Mehmet Özdoğan, Nezih Başgelen and Peter Kuniholm, 185-269. Istanbul: Archaeology and Art Publications.

Schirmer, Wulf. 1988. „Zu den Bauten des Çayönü Tepesi.“ Anatolica XV, 139-159.

Schirmer, Wulf. 1990. “Some aspects of buildings at the “aceramic-neolithic” settlement of Çayönü Tepesi.” World Archaeology 21, 3: 363-387.

On Nevalı Çori:

Hauptmann, Harald. 1988. “Nevalı Cori: Architektur.” Anatolica XV: 99-110.

Hauptmann, Harald. 1993. “Ein Kultgebäude in Nevali Çori.” In Between the Rivers and over the Mountains. Archaeologica Anatolica et Mesopotamica Alba Palmieri dedicata, edited by Marcella Frangipane, Harald Hauptmann, Mario Liverani, Paolo Matthiae and Machteld J. Mellink: 37-69. Rom: Gruppo Editoriale Internazionale-Roma.

Hauptmann, Harald. 1999. “The Urfa Region.” In Neolithic in Turkey, edited by Mehmet Özdoğan and Nezih Başgelen, 65-86. Istanbul: Arkeoloji ve Sanat Yayınları.

On Çatalhöyük:

Hodder, I. 2011. Çatalhöyük. The Leopard´s Tale. London: Thames and Hudson.

On Neolithic death and skull cult (just a few points to start from, there is vast literature on this):

Bienert, H.-D. 1991. Skull Cult in the Prehistoric Near East, Journal of Prehistoric Religion 5, 9-23.

Bonogofsky, M. 2005. A bioarchaeological study of plastered skulls from Anatolia: New discoveries and interpretations, International Journal of Osteoarchaeology 15, 124-135.

Croucher, K. 2012. Death and Dying in the Neolithic Near East. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lichter, C. 2007. Geschnitten oder am Stück? Totenritual und Leichenbehandlung im jungsteinzeitlichen Anatolien, in: Badisches Landesmuseum Karlsruhe (Hrsg.), Vor 12000 Jahren in Anatolien. Die ältesten Monumente der Menschheit. Begleitband zur großen Landesaustellung Baden-Württemberg im Badischen Landesmuseum 2007, 246-257.

Very interesting and thought provoking. Strange how deliberate ‘backfilling’ continued to appear as a Neolithic phenomenon thousands of years later in causewayed camps of the British Isles.

I like the title! The head was clearly the most revered (if that’s the right assumption) part of the body. The rest was presumably left, literally, for the birds.

Yes, and it`s not only the backfilling. Breaking off the heads of figurines is another social practise that you can follow throughout the Neolithic and Europe. Of course these practises will likely have taken on different meanings in different cultural contexts – but they could be part of the original ‘Neolithic Package’.

Based on my research about depicted sign language the “missing head” is part and parcel of the sign language based system. Most compositions are based on a Body template. This allowed the composer to position the signs in relation to the Body. For example, Signs could be place over an Eye and even though not depicted the allusion to the Eye would be incorporated into the message. In the Gobekli depiction of a Headless Body the body is composed of a Vertical Rectangle that means, “a vertical-place” –a place having height and depth. The Arm on the Left (in signing the Left indicates, “the east”) and points to the Shoulder that, as a sign, that indicates, “the edge” (of the earth). The Head/Face, normally means, “his appearance” which, in this case, is absent. The general meaning is, “the one, in the east, unseen.” The Right Arm points downward and indicates,” the one in the west,” also “unseen.”

The Large, Long Throat-ed Bird is the sign for, “the great one, that flies.” In sign language the gesture sign for Bird and Flight are the same. The Eye of the Bird” is the sign for, “a center” and alludes to the Eye of the Sun, a metaphor describing Venus. The Long Throat of the Bird alludes to the Throat as , “a long, connecting tunnel” between the Stomach viewed as, “a container” and the Mouth as, “a water source.” There are numerous ancient compositions that contain such references to the spirits of deceased leaders as arising from the underworld to the earth’s surface where, in pools of water, they “await their flight to the sky.” as a form of rebirth or resurrection. Venus was considered the ultimate destination for great leaders described as “warrior-priests.” The Phallus simply indicates gender and is composed of the signs for, “a stopping place (of) the male-spirit, on the side of, (the earth,– the Body).”

For more details see:

https://www.academia.edu/32713990/Gobekli_Tepe_The_Vultures_Part_1

and

https://www.academia.edu/32713990/Gobekli_Tepe_The_Vultures_Part_2

So the megalithic tradition seen in western Europe from 4/5000 bc could well have descended from the much earlier Anatolian tradition, with modifications caused by cultural ‘drift’ and change through time? But how is the appearance of the jaw dropping skill and scale of Gubekli Tepe to be explained, particularly within such a relatively brief period since the Lower Dryas?

Thanks for your interesting comments, here are just a few quick thoughts from me.

I wouldn´t say that the megalithic tradition of western Europe is directly interrelated with the Göbekli Tepe type monuments. Neolithic megaliths are absent from central Anatolia and southeastern Europe, so they were not part of the package distributed on that way to Europe. The examples of megalithic buildings from the Mediterranean – the temples of Malta, or the Taulas of Menorca – are much younger and very different. So neither that way works.

The “why then and there”-question is one of the most discussed issues in the field of Neolithic Near Eastern archaeology right now. In his book “The birth of the gods and the origins of agriculture” Cauvin has given an interesting answer. He argued that the transition to the Neolithic was influenced or started by a change in thinking, by the use of symbols that preceded agriculture. Göbekli Tepe is evidence that he was right in that (and of course there is also the Natufian with its rich symbolism before GT). However, symbols and art have been around much longer (Palaeolithic cave art, figurines), so most likely several factors are involved here. I think that the climatic optimum following the younger Dryas was surely one of these factors. An environment that was suddenly rich in resources made the constant struggle for survival less central and allowed for human creativity to unfold.

Thanks,Oliver. I had no doubt there had been a change, possibly even a revolution in late pleistocene thinking and symbolism. I have not read any Cauvin and will search for examples from my local bookshop; I must say I’m inclined to a more materialist,’down to earth’ perspective supporting the view that economic change alters social thinking. Not really Marxist but the argument that the Natufians ‘invented’ agriculture for survival reasons during the increasingly arid Younger Dryas environment does hold more water for me than saying their descendents would voluntarily opt for gritty cereal gruel rather than a juicy antelope steak even though herds must have increased once warmer climatic conditions returned.

I’m still left with wondering where the quantum leap in the skills needed to construct GT came from!

Personally, if the both of you don’t mind me chimig in, I am convinced we’re actually not really talking about a ‘quantum leap’ here, but only see the (in stone) preserved result of a longer development of related sites. Regarding your steak over gruel argument (which certainly holds some valuable thought), I’d also like to point out our thoughts on the probable role of early alcoholic brewings and the economic pressure from large scale feasting in the context of Göbekli Tepe’s monuments: //dainstblog.com/2016/04/24/out-for-a-beer-at-the-dawn-of-agriculture

Yesterday, on a page about the pillar 43 and fox paper, I was asking you about the diameter of the hole on the pillar depicted here. One of the workers is leaning upon it, and there is a some book, presumably of A4 format there. I think that the hole is 7-12 cm wide, but I am guessing here.. This particular stone was I think a sighting stone for observing a passage of (some heavenly objects). What can you tell us about it ? How was it initially aligned ? Where it stood ? What is the exact diameter of that little hole (if I am not asking too much) ?

The alternative explanation, aside from astronomical ones, is that the hole was used for spying on passage of herds, for the purpose of hunting. Dual use is of course possible too.

There a some important points to note about this particular stone (which we never addressed as ‘sighting stone’, by the way) to be noted here:

1. At current state of research it cannot be said if the opening really is going all the way through the stone, it could as well be just a cavity similar to other examples known from the site.

2. With a view to the rest of the excavated parts of Enclosure D it seems likely that the enclosure wall is running right behind that stone, thus blocking any possible line of sight (*if* the opening really was complete).

3. Again we have to consider the possibility to deal with subterranean structures here. In this case, it would’ve been impossible to see anything (in particular anything in the sky) through this opening (if it was one).

I would just add to Jens’ comments that we don’t know whether this stone is in it’s original position. Many pillars, sculpted pieces and stones were reused and placed in secondary positions at GT. And in most of these cases, there is just no way of knowing where the workpieces originally might have been placed.

The stone is bored completely through. If the picture is zoomed, one can see through to the other side. It has a height of a man, so it is suitable for viewing through, either for spying on herds in distance, or for observing star transits at night, or both. Diameter can be roughly judged by comparing with the A4 notebook on top of it, and with human heads nearby.

A star transit across the hole would last about 15 minutes if observed from about one step distance, more if one moves closer. The stone is at that picture between central pillars, so I presumed that it was found there, which is exactly where it should have been.

Whenever you find sighting stones like that one, please note exactly the direction to which they point, and their position. Same goes for central T-pillars. Otherwise you loose some possibly very important information just because you don’t care about astronomy. Well sir, I wonder if you have ever observed how magnificent a pristine night sky looks in true pitch darkness without modern pollution by light and smog ?.Those people were viewing it every day, and had no electricity to distract them. Surely they were stargazers.

Anyway, I have a valid hypothesis about what they were observing, when, and why and was hoping that you record this kind of data (the azimuths of big stones), but apparently you don’t. I regret that this is so. Please do in the future.

Nonetheless, if you have pictures of that stone in original position, perhaps the necessary positional details can be discerned from those old pictures. As for the diameter, this anyone who can access that particular can measure in seconds at least with a ruler, if not micrometer, so there is really no excuse of that not being done, other than perhaps a revulsion against any idea that the site might have had some astronomy related purposes. this you might not know, but it can be checked if you supply the positional data of the pillars to those of us who are able to analyze them properly. I think that it would be rather miraculous if they did not use the top-of-the-hill position for some splendid sightings.

Seems we were talking about different stones then, you’re referring to Pillar 30 here but I assume Collins means the stone in the northern perimeter of Enclosure D. Almost all photos here and published elsewhere do show the original position (the ‘in situ’ find position that is) as we usually do not change of move the megalithic stones (with rare exception if working security makes this necessary, but in this case it always will be indicated).

Ok, so you mean Pillar 30. This is one of the T-shaped pillars in the ring wall of Enclosure D. It does not stand between the central pillars, but to the northeast of Pillar 18 (=eastern central pillar). Although the pillar shaft is broken, there is no indication so far that it was moved in prehistory. Nor did we move it.

And, by the way, contextual information is the basis of every interpretation in archaeology. We record the position, measurements, characteristics etc. of every find. That´s probably why the internet is full of astronomic interpretations of GT – because you can get that data from our plans and documentation. Whether those interpretations are well-founded is another question of course. All you can see through that hole at the moment are adjacent pillars and wallstones. If the enclosures were roofed, that would also be very much what you saw in the Neolithic. The pillars at GT have holes in different sizes, in many cases they take the form of loops. A simple interpretation for theses holes is that the pillars were adorned during ceremonies.

I was referring to the top-most image on this page. If that is a T-pillar 30, I can’t tell from the perspective on the photo.

Fair enough, I could add that the holes in pillars might have been used for attaching ropes to lift them by some suitable contraption, perhaps in ceremonies, but maybe also during transport from the quarry. Detailed close-up examination of the erosion marks, shape and dimensions of that and other holes might be able to resolve for what were they used for. On the image above the hole appears very circular and having a properly rounded edge.

Regarding the roofing, it is quite possible that the structure had a roof. If it was used for 18 centuries, and stood in open, then there should have been traces of erosion by rain. Such traces are not visible on central T-pillars, I think, at least not in the enclosure D. Some others, more recent pillar appear eroded, though. Even in such case (and perhaps especially in such case, sighting holes in the wall would be required. We call them windows today. Useful things they are.

Regarding Andrew Collins, and the rib bone plaque, there appears to be an indication of a sighting hole between the pillars. A small fist sized window would suffice for the stated purpose. Are you telling me that there was no such thing discovered thus far, and that the envisioning images of a sighting stone (or window in the enclosure wall) by Andrew are not supported by excavated facts ?

I think you are right – windows are useful things. Less so in subterranean structures. Like the ones at GT most likely were. That may be the reason why there are no windows in the enclosure walls. And yes, I am telling you that Andrew Collins’ ‘reconstructions’ are not based on excavated facts.

As of yet, it is hard to actually say how long these enclosures were really in use or even open before they have been backfilled. I don’t know where your information on the ‘erosion’ of certain pillars come from, but usually it is those pillars very close to the surface which show some damage – either by physical force (due to recent farming activity) or, more often, by congelifraction.

And yes, we are trying to tell you that there was no such thing as a ‘sighting stone’ discovered as of yet. At current state of research there simply are no windows in these enclosure walls. The workpiece in question here, north of both central pillars of Enclosure D has a cavity, but we cannot determine if this opening really is a ‘hole’ through the stone – that cavity is still filled with sediment at this point and, as I pointed out above, (judging by neighbouring features unearthed in deep soundings), behind this piece we have to expect at least one of the enclosure walls (followed by mighty layers of more sediment), effectively blocking any attempt to take a bearing.

I don’t know what wall are you talking about. I don’t see any holes in the wall. I see three guys on the picture. Between one of them and a ladder there is a stone block with a small circular hole on top, in the middle. There is a notebook on top of it. The caption of the picture says : “The filling material of Enclosure D (Photo: K. Schmidt, Copyright DAI).” I was referring to that small circular hole in that stone block. It goes all the way through, so one can see through. Why had anyone bother to make that particular hole ? What is your opinion ? (Is that a p 30, by the way ?)

What makes you think that the pillars were located underground ? This is not a cave, but a pile of rubble all around them, as far as I can tell.

This is not “a p. 30”, it’s Pillar 30 in the ringwall of Enclosure D. No sighting stone, a T-shaped pillar of about 4 m height. Jens referred to the stone that Collins believes to be a sighting stone. That is another stone, not Pillar 30. That the Enclosures are subterranean is the result of stratigraphic and building research on site. The enclosures were set into a pre-existing mound.

Thank you for your answers. Despite some misunderstandings in the process, you have been helpful.

I have one last question: I’ve seen maps of the whole area, but none of them has a scale on a side, so I do not know how large is the site. What is the approximate air distance from enclosures D and F, for instance, and are they on the same elevation ? Thanks again.

Our published plans usually come with scale (or at least note on scale), cf. here or here ([external link], Fig. 3 – also with eleveation contour lines).

Also, as Oliver pointed out, we were apparently talking about two different work pieces – I was relating to a stone with a cavity in the northern perimeter of Enclosure D often referred to as ‘sighting stone’ in internet discussions (a term we never introduced or used), you seem to mean Pillar 30. The remark about ‘subterranean structures’ does not refer to the filling inside the enclosures, but more to the thick layers of sediment *outsdide* these. Still ongoing stratigraphic studies and building research (regarding the enclosing walls in particular) offer a great insight into these line of thoughst and do indeed suggest the possibility that (at least some of) the enclosures were set into an already existing mound – as Oliver mentioned.

I certainly agree on Jens regarding the longer process. Here is a very good article by Trevor Watkins that sums up much of the current debate: http://jnls.cup.org/pdftext.do?componentId=9438159&jid=AQY&freeFlag=F

Jens, I was unaware of any discoveries that could described as architecturally seminal. Could you forward details? I’ll look up your article too Oliver.

Re the brewing of alcohol, I know that carved stone ‘vats’ with traces of fermentation have been found at GT and when reading this and knowing the culture was pre-agricultural in Schmidt’s assessment, was hit by the beautiful thought that the neolithic revolution had in fact originated in the quest for plentiful supplies of beer. For purely medicinal/spiritual reasons, of course..

Well, I was referring to *possible* forerunners of organic material which are not preserved. The technique applied with the limestone pillars and sculptures may well have originated on woodwork for instance. The article Oliver linked to is a great start to get a general understanding of the era and the long-term perspective we have to consider when viewing into this so-called revolution.

Regarding possible forerunners, we have for example the Natufian semi-round or round building from Ain Mallaha/Einan inside a settlement that also has produced ‘symbolic’ objects. Another case of early ‘communal buildings’ is Hallan Cemi in southeastern Turkey. The concept of communal/special buildings with close connections to belief systems/symbolism (in Hallan Cemi aurochs seems to have been of special importance) seems indeed to start earlier than GT. What is special about Göbekli is (a) the monumentality and the richness of depictions, and (b) that the site seems to contain only special buildings. In another post I have shortly described that the T-shaped pillars are a specific of the Urfa region. To the east we have standing stones without T-heads, to the west special buildings with wooden supports. Yet the whole region shares the same symbolic objects. So, to some degree, the appearance of monumental stone buildings and T-shaped pillars seems to be a special cultural trait of the region between the upper Balikh and Chabur rivers.

Well, we’ll never know how well developed Natufian woodworking skills were, I suppose. Stonehenge in England clearly shows how such skills were carried over into megalith construction but the mortice and tenon joints used were what would be seen in the construction of homes, not fine carving. Are the standing stones farther east that you mentioned, Oliver, a potential forerunner of the GT pillars? Are they carved at all?

The eastern pillars are contemporaneous to GT, they are carved, but have no decorations as far as I know. Have a look here, Gusir Höyük: http://www.atlasdergisi.com/kesfet/arkeoloji/yerlesik-avcilar-gusir-hoyuk-siirt.html

I would rate Natufian carving skills quite high judging from bone objects like the el-Kebara sickle haft. Whether this implies monumental wood carvings is another issue, of course.

Thanks Oliver. I read your post referring to T-shaped pillars at Sefer Tepe, Karahan Tepe and Hamzan Tepe with interest and see they’ve not yet been excavated. Still early days in researching this part of Anatolia then..

Very interesting also to read that the wild, undomesticated grains were not really suitable for bread making and better for beer (and gruel),suggesting the fermentation of alcohol for periodic feasting may well have been the main driving force behind the adoption of agriculture. Grain as a serious alternative to meat (except in very hard times) would presumably had to await domesticated grains of larger size?

Jens,

I just listened to your podcast interview on Archaeology Podcast Network. Especially after listening to the Joe Rogan interview of Hancock vs Michael Shermer, it was nice to have a reasonable voice about the site and I appreciate all the firsthand information you brought to the show. I look forward to reading this blog more in the future now that I know about it, and even more to visiting Gobklitepe in the near future!

Also, I heard you mention that the site is not open to tourists at all times. What are the times of year I would be able to visit?

Best regards,

Ben Williams

Thanks a lot, Ben. Yes, the site is currently closed due to shelter construction, but re-opening was just announced for mid-July. We don’t really have much to do with tourism development there though, everything regarding these issues are managed by the Ministry of Culture and Tourism. However, in the past the site used to be open to visitors during the day hours.

Thanks for the reply. I want keep an eye on the accessible times after my unfortunate experience on Santorini when the Akrotiri site I had come to see was closed, curiously also to put a roof over the site.

Have a fantastic day!

You’re welcome. Yes, preservation really has become top priority for archaeological sites under excavation, too. Which is a good thing in my opinion.

Have a great weekend too.

Hi,

For me, the “idoletto di arnesano” looks like GT artefacts. Is it possible that east anatolian people going to Creta 7000 y BCE, and after to Italy, made this idol ?

What is your opinion ?

http://www.salentoacolory.it/lidoletto-di-arnesano/

The Arnesano figurine is Final Neolithic, 3rd millennium BC. This would be a very long time for PPN traits to survive. I think the similar way to depict human facial features has rather something to do with the technique of carving these faces from soft stone. There are very similar heads from wooden sculptures from completely different cultural and chronological contexts.

Thank you oliver