A few kilometres northeast of modern Şanlıurfa in south-eastern Turkey, the tell of Göbekli Tepe is situated on the highest point of the otherwise barren Germuş mountain range. Rising 15 metres and with an area of about 9 hectares, the completely man-made mound covers the earliest known monumental cult architecture in the ancient Near East. Constructed by hunter-gatherers right after the end of the last Ice Age, they also intentionally buried it about 10,000 years ago.

Göbekli Tepe has been known to archaeologists since the 1960s, when a joint survey team from the Universities of Istanbul and Chicago under the direction of Halet Çambel and Robert Braidwood observed numerous flint artefacts littering the surface of the mound. However, the monumental architecture remained undetected, and was eventually discovered by Klaus Schmidt on a grand tour of important south-eastern Turkish Neolithic sites in 1994. In addition to the high density of flint tools and flakes, his eye was caught by large limestone blocks which reminded him of another nearby Neolithic site where he had worked several years before: Nevalı Çori – where, among others, a building with monolithic T- pillars was discovered for the first time. These peculiar T-shapes reminded Schmidt of the worked stone peeking out of the surface at Göbekli Tepe. Excavations at this site began the next year.

In about 22 years of ongoing fieldwork, the German Archaeological Institute and the Şanlıurfa Museum have revealed a totally unexpected monumental architecture at Göbekli Tepe, dating to the earliest Neolithic period. No typical domestic structures have yet been found, leading to the interpretation of Göbekli Tepe as a ritual centre for gathering and feasting. The people creating these megalithic monuments were still highly mobile hunter-foragers and the site’s material culture corroborates this: substantial amounts of bones exclusively from hunted wild animals, and a stone tool inventory comprising a wide range of projectile points. Osteological investigations and botanical studies show that animal husbandry was not practiced at Göbekli Tepe and domesticated plants were unknown.

- The mound of Göbekli Tepe seen from the south. (Photo: K. Schmidt, DAI)

- The mound of Göbekli Tepe seen from the south. (German Archaeological Institute, Photo: E. Kücük)

- Aerial of the so-called main excavation area of Göbekli Tepe, the older monumental enclosures in the lower center. (Photo: E. Kücük, DAI)

- Schematic plan of Göbekli Tepe’s main excavation area (plus Enclosure E). (Plan: K. Schmidt & J. Notroff, DAI)

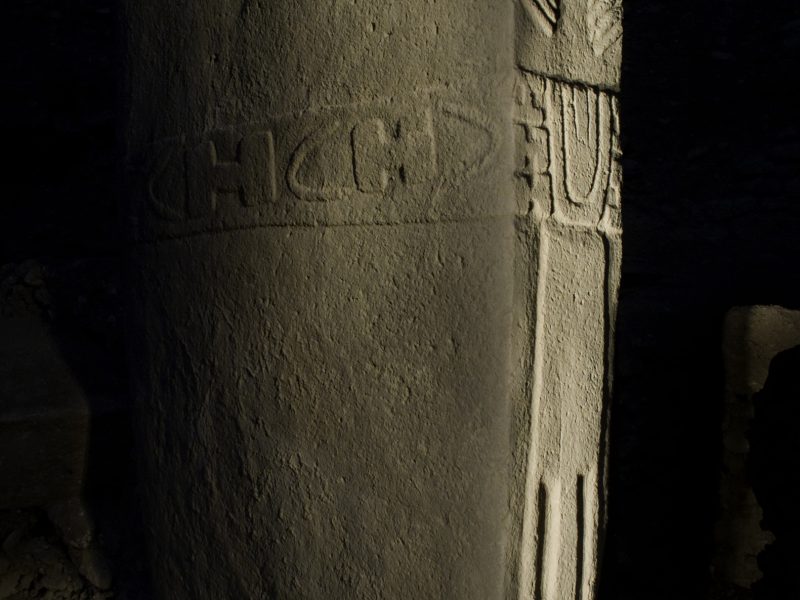

It is currently possible to distinguish two different phases at Göbekli Tepe although this will undoubtedly change with continued research. The site is characterised by an older layer dating to the Pre-Pottery Neolithic (PPN) A period (ca. 9,600-8,800 calBC) which produced monumental circular huge T-shaped pillars arranged in circle-like enclosures around two even taller central pillars and a younger layer, early and middle PPN B (c. 8,800-7,000 calBC) in date. It consists of smaller rectangular buildings containing often only two small central pillars or even none at all. These may be reduced variations (or later adaptations) of the older and considerably larger monuments, of which four were excavated in the main excavation area in the mound’s southern depression. Notably these structures, labelled Enclosures A, B, C, and D, were apparently backfilled intentionally at the end of their use-lives. Enclosure D, the best preserved of the circular buildings, serves to give an impression of the general layout and set-up of these enclosures.

In the centre two colossal pillars, measuring about 5.5 m, are founded in shallow pedestals carved out of the carefully smoothed bedrock. This central pair of pillars is surrounded by a circle formed of similar, but slightly smaller pillars which are connected by stone walls and benches. While these surrounding pillars often are decorated with depictions of animals like foxes, aurochs, birds, snakes, and spiders, the central pair in particular illustrates the anthropomorphic character of the T-pillars. They clearly display arms depicted in relief on the pillars’ shafts, with hands brought together above the abdomen, pointing to the middle of the waist. Belts and loincloths underline this impression and emphasize the human-like appearance of these pillars. Their larger-than-life and highly abstracted representation is intentionally chosen and not owed to deficient craftsmanship, as other finds like the much more naturalistic animal and human sculptures clearly demonstrate. This suggests that whatever the larger-than-life T-pillars are meant to depict and embody is on a different level than the life-sized sculptures in the iconography of Göbekli Tepe and the Neolithic in Upper Mesopotamia.

- Enclosure D (Photo: DAI).

- Detail of Pillar 18 showing hands, belt, and loincloth in relief. (Photo: N. Becker, DAI)

While naturalistic and abstract depictions find their most monumental manifestation on the T-shaped pillars, there are others. Similar and clearly related iconography also occurs on functional objects like so-called shaft straighteners, on stone bowls and cups, as well as on small stone tablets which apparently do not have any other function than to bear these signs. Furthermore, these objects are not restricted to Göbekli Tepe and the few other sites with T-shaped pillars in its closer vicinity, but are known from places up to 200 km around the site. A spiritual concept seems to have linked these sites to each other, suggesting a larger cultic community among PPN mobile groups in Upper Mesopotamia, tied in a network of communication and exchange.

Ethnologic and historic analogies emphasize the importance of regular gatherings and collective activities as means of maintaining social cohesion in hunter-gatherer communities. Gatherings also serve other purposes like the exchange of information, goods, and marriage partners. Such large-scale gatherings naturally need to be established in locations that are known and easily accessible for the participating groups.

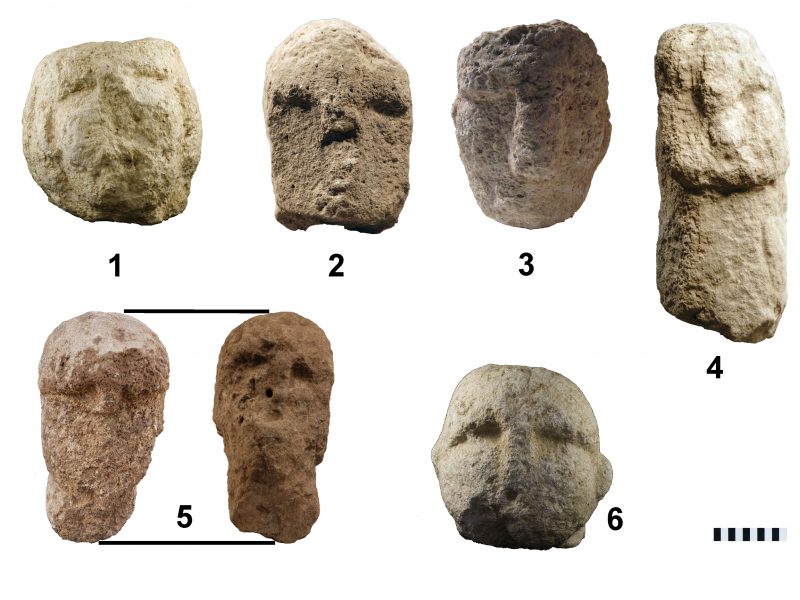

- Limestone head from Göbekli Tepe, supposedly part of a sculpture similar to ‘Urfa Man’ (Photo: N. Becker, DAI).

- Collection of plaquettes bearing iconographic symbolism from Göbekli Tepe. (Photo: N. Becker, DAI)

The topographical situation of Göbekli Tepe as a landmark overlooking the surrounding plains, seem a perfectly suitable central space for these groups and people inhabiting the wider region. Large communal tasks executed as collective work events, reflected in the apparently continuous construction activity at Göbekli Tepe, provided a unifying reason for people to come together. Additionally ethnographic studies provide more examples demonstrating that work forces necessary for such collaborative projects can be gathered with the prospect of lavish feasts.

That this may have been the case at Göbekli Tepe is further corroborated by a closer look at the massive amount of filling material of the enclosures, which consists of limestone rubble, flint artefacts, fragments of stone vessels, other ground stone tools, and in particular an impressively large numbers of animal bones – above all gazelle and aurochs. These remains hint at the consumption of enormous amounts of meat, most likely during feasts framing these large-scale meetings and communal activities, including monument construction.

Current distribution of sites with T-shaped pillars and with simple limestone stelae (modified after Schmidt 2006; Copyright DAI).

Repetitive feasting at Göbekli Tepe may have played an essential role not only in creating and strengthening social bonds among the individuals and groups meeting there, but must also have stressed the economic potential of these hunter-gatherers to repeatedly feed such large crowds. In response to this pressure, new food resources and processing techniques may have been explored, subsequently paving the way for a complete change in subsistence strategy. In this scenario, the early appearance of monumental religious architecture motivating work feasts to draw as many hands as possible for the execution of complex, collective tasks is changing our understanding of one of the key moments in human history: the emergence of agriculture and animal husbandry – and the onset of food production and the Neolithic way of live.

This text was originally written by Jens Notroff & Oliver Dietrich for and published at the weblog of Boston University’s American School of Oriental Research: The Ancient Near East Today – Current News About The Ancient Past [external link], July 2017: Vol. V, No. 7 under the title “Göbekli Tepe: Neolithic Gathering and Feasting at the Beginning of Food Production” [external link].

A clear, concise summary! Goodoh for Boston University!

A brilliant overview of the research you guys have collated thus far.

The centrality of the faceless T-shaped and anthropomorphic but abstract monoliths in Gobekli, as well as other Neolithic sites in the nearby radius, has long fascinated me.

I have wondered (and this is mere speculation on my part), whether their larger-than-life human-like design and the fact that they tower over the animals and surrounding environment on the tell, might suggest that this indicates a significant shift in worldview from the earlier “cave art” beliefs. In these, Paleolithic people appear to have seen themselves as simply “part” of their natural world, on a similar level to the animals depicted – I suppose a sort of “animosity” religious outlook, if it isn’t anachronistic to say that.

But with Gobekli Tepe, stylized human figures take centre stage for veneration and ritual focus, towering above the animals that lie beneath and the surrounding landscape. Does this suggest a shift to a more “anthropocentric” worldview in which humans are believed to ‘above’ the rest of nature and perhaps able to exert a kind of ‘mastery’ over the wild forces of nature represented by the fearsome beasts?

I might be completely off here but that’s my thinking.

Thanks a lot, Sean. The noticeable change in art and the depiction of humans and animals from Paleolithic and Neolithic is indeed discussed as expression of a changing mindset due to the new, i.e. Neolithic, way of living. The focus does indeed seem to shift from the depiction of large animals and only rarely humans to an emphasis of human beings – significantly larger (life- and more than life-sized) anthropomorphic depictions as those T-pillars at Göbekli Tape (which also show attributed animals in form of reliefs).

So, your thoughts don’t seem completely off.

Thanks, that’s what I had noticed when comparing the art from the Paleolithic to the Neolithic.

Do we know specifically what spurred this change in mindset in the early Neolithic, given that GT was constructed prior to full sendentism and agriculture? Was it the semi-sedentary lifestyle that has been attested for this period in the Near East (I think prior to and concurrent with GT, i.e. Jericho, Nevali Cori)? Something seems to have spurred them to take a greater look at the human form, at themselves I suppose. Presumably, their lifestyle must have afforded them more time for reflection than that of their Paleolithic ancestors. Perhaps the greater flow of ideas in a large complex like GT, where disparate groups of hunters met from across a wide radius, also spurred their creativity.

The conscious decision to choose an abstract design for the T-pillars is also intriguing, since as you say they had the ability to depict human facial features in a naturalistic manner (such as with, I think, obsidian eyes and the like). I’m impressed by that degree of intellect – the fact it was a choice rather than dictated by lack of skill, to distinguish the “special purpose communal buildings” from simple domestic dwellings.

I also find it worthy of note that a millennium or so after GT, at the settlement site of Catalhoyuk (where the people are now farmers), the special purpose buildings seem to no longer exist (please correct me if wrong here). Here domestic dwellings appear to have served as the site of the skull cult as opposed to public buildings that aren’t used for living in, as with GT and Nevali Cori , (although its interesting that the “headless man” symbol seems to have persisted down the years and outlived the transition to a fully agricultural, sedentary life). Were they cult buildings I guess, a “hunter-gatherer” peculiarity that served no purpose in an agricultural setting?

It’s a very interesting era to consider in terms of the broadening of the human imagination.

There is indeed much debate about the reasons for this shift and the possible cognitive and social background behind it. I would highly recommend a look into Jacques Cauvin’s “Birth Gods and Origins Agriculture” (New Studies in Archaeology, Cambridge University Press 2008) for a start and Trevor Watkins gives a great overview on the current discourse (incl. many references) in his Antiquity article from 2010 (https://www.cambridge.org/core/services/aop-cambridge-core/content/view/S0003598X00100122).

Spelling error above, I meant to say “animistic” not “animosity”!

The “demon” is the eye of the beholder. The “T” shaped gesture sign is found in caves much older than GT. The representation for “importance” was expressed through relative size in ancient compositions. It would be only natural that this rule was carried over to the carvings in stone.

The signs held meaning independent of their inclusion into the overall composition. Thus the meaning of an “arm” does not directly relate to the “T” Form. The “T” shaped sign is historically documented as meaning, “below.” It’s large size indicates “great” thus, t”he great below” or “the great. underworld.” The “arm” represents, a warrior or a defender, positional, within, the underworld. Ancient compositions may be viewed as conglomerates where the total form is composed of multiple entities that maintain their own unique properties.

Attempting to track cultural change through changes in depictions is fraught with difficulty. It is tantamount to attempting to track cultural change by doing a word count on a paragraph written in an unknown language –well, even more difficult than that. It is unlikely that people would change their entire language due to the invention of a new tool.

The first sentence should have read, the demon is in the eye of the beholder. I didn’t mean to be cryptic, I was thinking that ancient depictions of animals are often thought to represent gods or ferocious beasts. The Egyptian imagery of the “demon” Ammit is a compound or conglomerate of imagery related to other animals such as a Hippopotamus, a Feline, and a Crocodile, among others. Although younger than GT, the Egyptians carried on, or inherited, the system of depicted sign language used in their tomb panels. One did not need to remember thousands of ancient “gods” as such imagery was merely an association related to that particular animal. Most people would have known that a Feline was a prowling hunter of the night while the Bird of Prey (for the Egyptians, a Falcon, in many other cultures, an Eagle) was a flying hunter of the daytime. These two animals became the associations used to depict the Daytime and Nocturnal Sun. The “griffin” as a combination of both animals was simply a generalized term for the Sun.

My paper related to Ammit can be found on academia.edu and the principles delineated in that paper apply to the depictions of animals on GT’s pillars.

Hi Cliff, I am also interested in your paper about Ammit but the link associated with your name above doesn’t take me anywhere. Please advise where to find you in Academia.

Thank you!

Luis

https://www.academia.edu/34113135/Ammit_The_Egyptian_Demon

I checked and this link seems to be OK’

You also can find me by searching Cliff Richey at academia.edu

Found it now! Thanks again.

Luis

Reblogged this on Voices and Visions.

Reblogged this on Rashid's Blog.

Excellent article. Too bad the site distribution locations map cannot be read.

Thanks for your comment and the compliments. Regarding the map: did you try clicking on it, does the bigger version opening then work?

Hi, I know this article is over a month old but I just had a chance to read it with its deserved attention and it was great.

I’m very interested in seeing more samples of those plaques with GT iconography. Is there a paper or site that shows an extended collection of such artifacts?

Thank you so much.

A word of thanks for the wonderful coverage of GT in the Tepe Telegrams. And a question: What has happened since 2017? Why have the postings stopped? Are there any plans of the Telegrams started again? Thanks for your response and best wishes!

Please disregard my last comment, which was a result of a misunderstanding. Sorry!