Ever since the so called Braidwood Symposium in 1953 (Braidwood et al. 1953), there has been a debate as to whether beer – and not bread – was the first product made from domesticated crops (e.g. Katz and Voigt 1986). Based on the discovery of grain at the site of Qalat Jarmo, and at the suggestion of the archaeo-botanist Sauer, Braidwood inquired whether or not the discovery of fermentation could have been the spark that triggered the targeted selection, and ultimately domestication, of certain crops. Fermented grain, which sees its starch transformed into sugars, is well known for its beneficial properties, including an increase in nutritional value, also making it easier to digest. Indeed, the participants at the aforementioned symposium eventually came to the consensus that early grain crops would have been far better suited to the production of gruel or beer than bread, especially considering that the glumes of primitive domesticated plants would have adhered to the grain. Even though this idea (fermentation) was raised frequently in subsequent years (Katz and Voigt 1986), particularly in the context of the previously noted advantages (higher nutritional value) afforded by this process, it was considered improbable that beer was actually produced. More recently, however, the discussion was revisited in a contibution by P. McGovern (2009) who presented preliminary results from chemical studies made on two stone vessels from the PPN necropolis at Körtik Tepe which yielded traces of tartaric acid that accrues during the wine production process (McGovern 2009: 81).

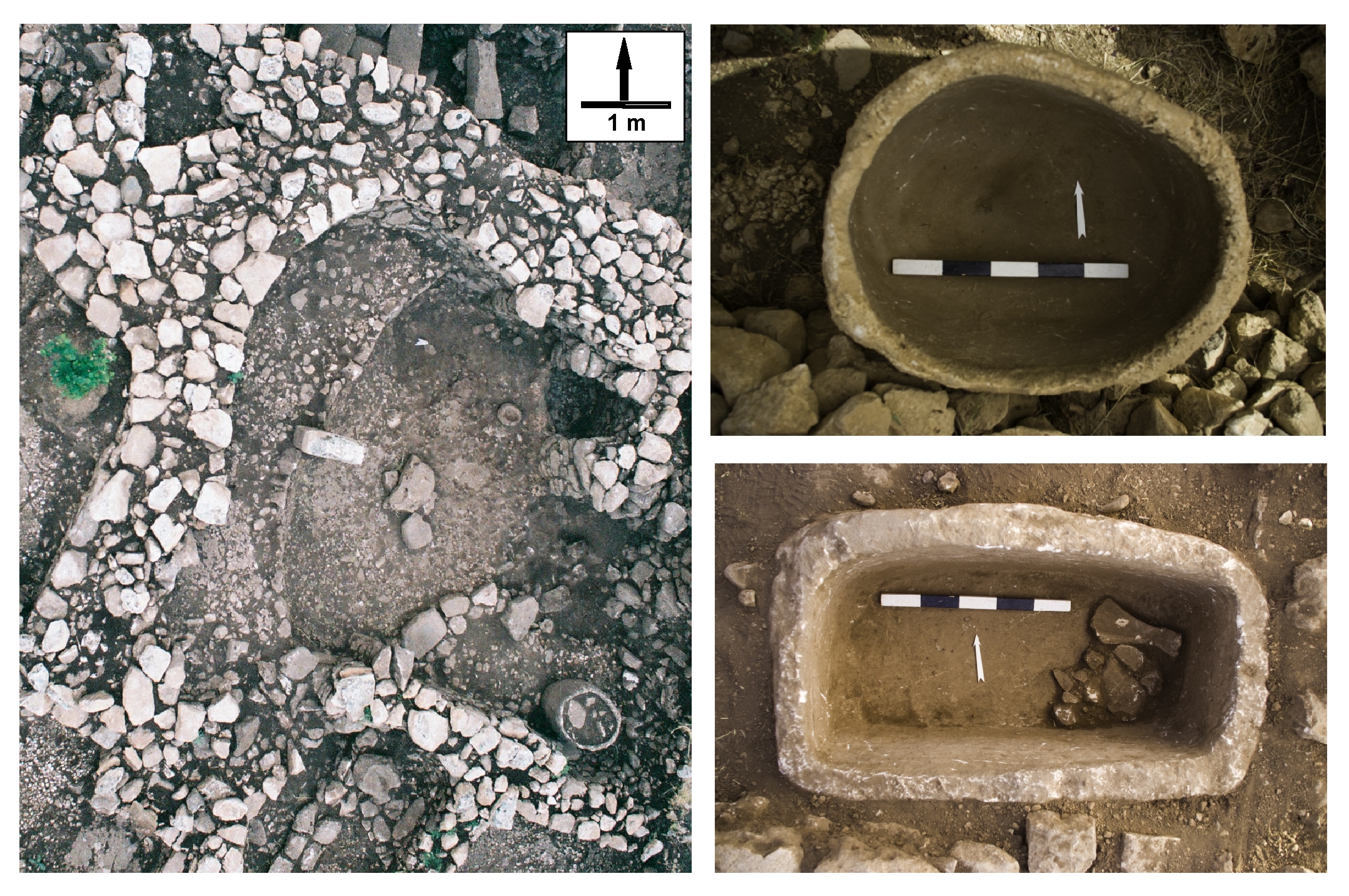

A barrel- (upper right) and a trough-like (lower right) limestone vessel from Göbekli Tepe (Photos: N. Becker, © DAI). Six vessels with capacities up to 160 l were discovered so far in situ (left).

Recently, further chemical analyses were conducted by M. Zarnkow (Technical University of Munich, Weihenstephan) on six large limestone vessels from Göbekli Tepe. These (barrel/trough-shaped) vessels, with capacities of up to 160 litres, were found in-situ in PPNB contexts at the site. Already during excavations it was noted that some vessels carried grey-black adhesions. A first set of analyses made on these substances returned partly positive for calcium oxalate, which develops in the course of the soaking, mashing and fermenting of grain. Although these intriguing results are only preliminary, they provide initial indications for the brewing of beer at Göbekli Tepe, thus provoking renewed discussions relating to the production and consumption of alcoholic beverages at this early time. Further, they are particularly significant in light of results from genetic analyses, undertaken by a team from the Norwegian University of Life Sciences in Oslo, which have suggested that the earliest domestication of grain occurred in the vicinity of the Karacadağ, i.e. very near to Göbekli Tepe (Heun et al. 1997 [external link]). Once again, we must ask whether the production of alcohol and the domestication of grain are interrelated. Finally, the aforementioned insights also provoke new questions relating to the use and consumption of alcohol at Göbekli Tepe, which may have been in the context of religiously motivated feasts and celebrations. Not surprisingly, such events are well attested in the ethnographic literature as a means of attracting and motivating large groups of people to undertake communal work and projects (Dietler and Herbich 1995).

Further reading:

Dietrich, O., Heun, M., Notroff, J, Schmidt, K., Zarnkow, M. (2012) The role of cult and feasting in the emergence of Neolithic communities. New evidence from Göbekli Tepe, south-eastern Turkey. Antiquity 86, 333: 674-695 (full text – external link).

Works cited:

Braidwood, R.J. & L.S. Braidwood. 1953. The Earliest Village Communities of Southwestern Asia. Journal of World History 1: 278–310.

Dietler, M. & I. Herbich 1995. Feasts and labor mobilization. Dissecting a fundamental economic practice, in Dietler, M. & B. Hayden (ed.), Feasts. Archaeological and ethnographic perspectives on food, politics, and power, 240-264. Washington / London: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Heun, M., R. Schäfer-Pregl, D. Klawan, R. Castagna, M. Accerbi, B. Borghi & F. Salamini. 1997. Site of Einkorn wheat domestication identified by DNA fingerprinting. Science 278: 1312-1314.

Katz, S.H. & M.M. Voigt. 1986. Bread and Beer: The Early Use of Cereals in the Human Diet. Expeditions 28 (2): 23-34.

McGovern, P.E. 2009. Uncorking the past. The quest for wine, beer, and other alcoholic beverages. Berkeley / Los Angeles / London: University of California Press.

Recent Comments