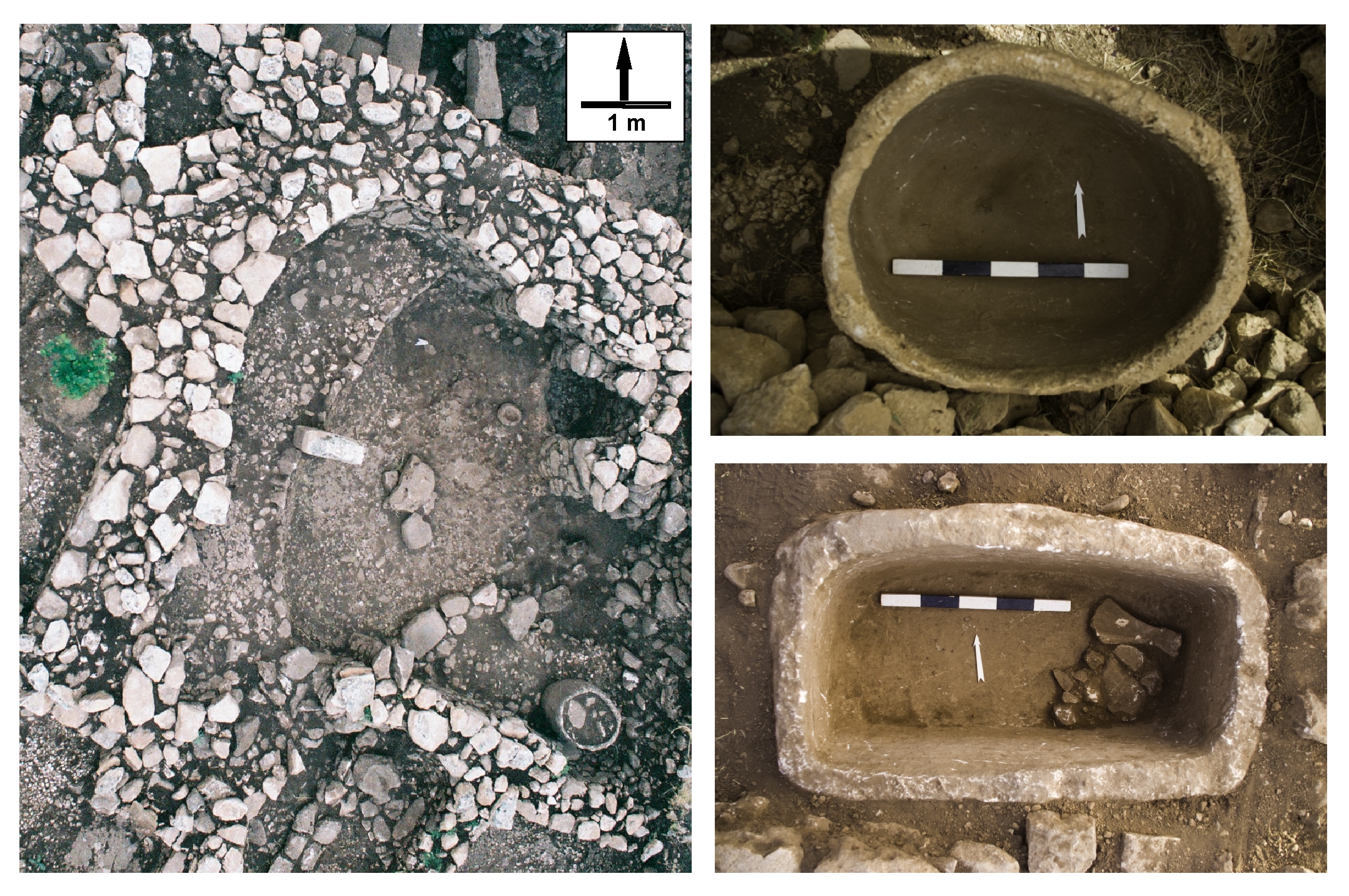

The relief on Pillar 51 in Enclosure H under different light conditions: at the moment of discovery with hard light from one side, on a cloudy day, and a night shot with directed light (Photos: N. Becker, (c) DAI).

Photographs are far from objective. They suggest meaning through the selection of the scene, but also through a certain perspective, focal point, light. Everyone who has held a camera in hands will agree on this, and it is also true for archaeological photographs.Many photos from Göbekli Tepe that you will see on this website or in publications were taken using artificial lighting. Often the background is black. This may be perceived as the attempt to create a certain mood. The objects, pillars and reliefs may appear more enigmatic, gloomy, related to another realm. As we interpret Göbekli Tepe as a site associated with Neolithic cult and religion, this would certainly fit.

A possibility for “objective” documentation? 3D-scan of Pillar 18 in Enclosure D (Graphics :Hochschule Karlsruhe, (c) DAI).

The explanation for the use of artificial lighting is another one however. Apart from some photographs, where it really was done for artistic reasons (see for example Berthold Steinhilber´s lightworks of Göbekli Tepe-external link), directed light is necessary in many cases to enhance the details of reliefs and surfaces in general.

If you visit Göbekli Tepe around the afternoon, like many people do, you could be slightly disappointed. Due to the sun´s position, many reliefs will not be visible very well. Some you will not be able see at all. Nearly every pillar at Göbekli Tepe has its “own time“, when reliefs will be best visible. Not in all cases really good, but best under direct sunlight conditions. Moreover, this “best moment” may also coincide with heavy shadows on other parts of the pillar. This is why night shots with directed light are the better choice in many cases.

Direct sunlight may also not have been the way the pillars were illuminated during Neolithic rituals. They do not seem to be made for this. The question whether the enclosures were roofed is still under debate, but there is also the possibility that activities took place after sunset and the reliefs were illuminated dramatically by fire.

But indifferent of this question, we are absolutely aware of the “dramatic” atmosphere generated in these pictures. And it turned out that some journals, including a few aimed at a scientific audience, liked the night shots much better than even good daylight images. It is clear that the images we use to describe a site or a find are not neutral. They can imply an interpretation of the site or of the artefact in question, or at least subtly influence the reader´s perception. Even a very neutral image, let´s say of an axe, with a white background and a scale, sends a message: that of absolute scientific objectivity.

So, here is the big question: How should we, as archaeologists, use images?

Recent Comments