Ulrich Mania & Felix Pirson

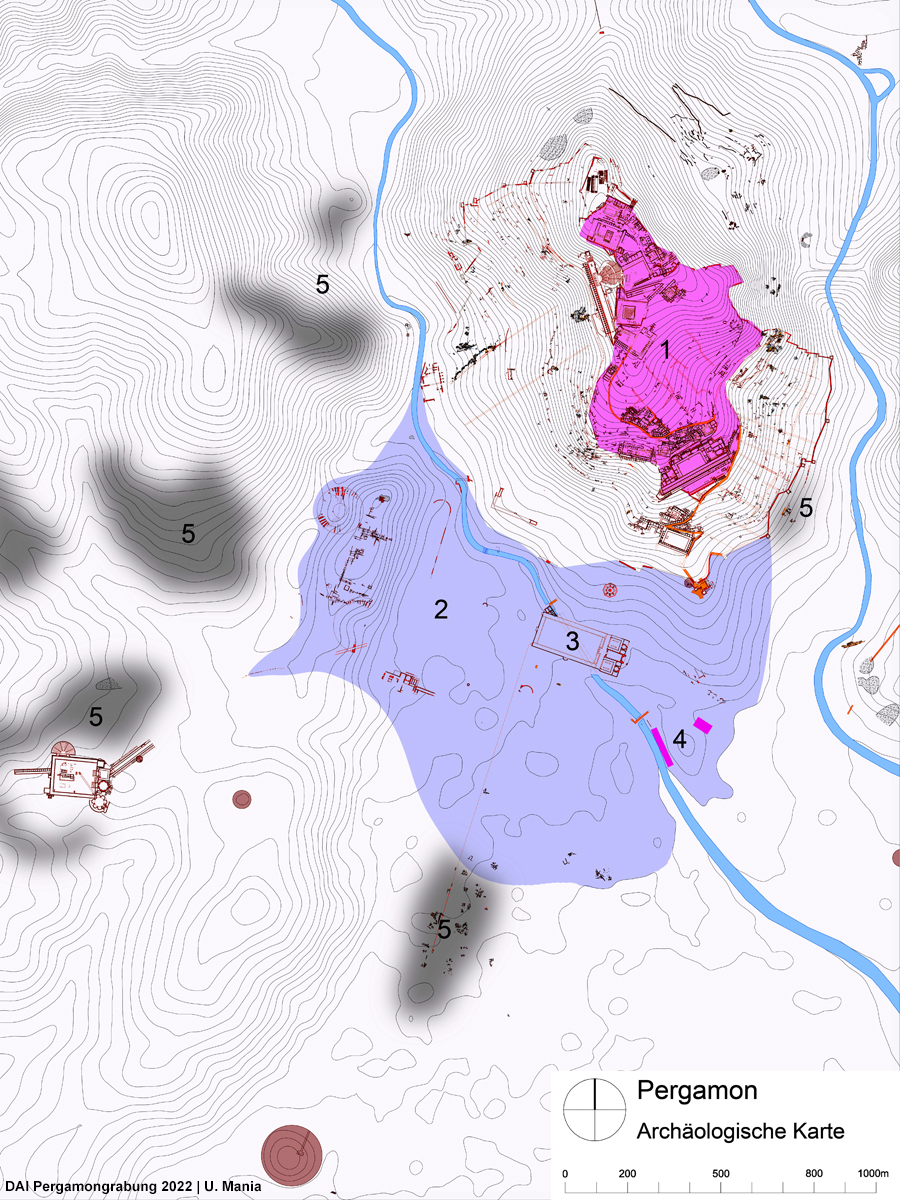

The settlement history and urban development of Pergamon are characterized by several phases of expansion, but also decline of the city, which repeatedly changed its character over time. After a history of about 250 years as a fortified Hellenistic residential city, Pergamon did not fundamentally change its face until the Roman Imperial period. In the course of the 1st century, Pergamon increasingly expanded beyond the city fortifications on the alluvial fan of the Selinus river (Fig. 1). Some large buildings of this city extension – the amphitheatre, the Roman theatre and the sanctuary of the Red Hall – have already been well studied. There is also partial knowledge of the necropolises in the vicinity of the lower city, which are known mainly from excavations by the Bergama Museum and were carried out as part of construction work in the city of Bergama. Of other buildings, such as the stadium, the baths or the streets, we only know the location and a few details. These findings and a recent survey in the vicinity of the Asklepieion make it possible to reconstruct the boundaries of the Roman Imperial lower city more and more accurately. It should not be forgotten that life also continued on the city hill in the Roman Imperial period and numerous smaller and larger construction projects were realized. This is indicated not only by the construction of the sanctuary for Trajan on the Acropolis at the beginning of the 2nd century, but also by the intensive Flavian modifications of the Gymnasion and the findings from the excavations in the so-called residential city on the middle city hill, which show that intensive settlement also took place here in the Roman Imperial period.

However, our knowledge of residential buildings and the buildings related to crafts and trade as well as the infrastructure of the lower town was still very limited. The same applies to the settlement history of Pergamon in the Late Antique and Early Byzantine periods. Against this background, the results of the archaeological work in 2021 and 2022 represent a significant enrichment.

1) Late Roman fortified area on the city hill; 2) Lower Roman Imperial town of Pergamon; 3) Red Hall; 4) Excavations of the Mosaic House and workshops along the Selinus River; 5) Roman necropolises

Fig. 2 Excavation in the filling of the Gots Wall

The so-called Late Roman Wall or Goths Wall is the first post-Hellenistic city fortification of Pergamon and thus marks an important turning point in the settlement history of the city. However, its dating has been controversial until now and could only be determined by linking the structure to historical events. For this reason, several sondages were carried out on the wall and in its fill during the 2021 season in order to be able to establish a chronological classification on the basis of stratified finding material (Fig. 2). We can now say that the fortification, which spans the city hill roughly along the earliest Hellenistic defensive ring and thus leaves large parts of the city hill and the entire lower city outside the defensive line, was built in the last third of the 3rd century at the earliest. Since younger artifacts are missing in the relatively extensive find material, a clearly later origin is at least extremely unlikely.

Although the wall consists almost exclusively of spolia, hardly any marble elements were used. It can be concluded from this that although the material of abandoned residential buildings – presumably mainly from outside the new wall ring – was used for the wall, the public buildings were still intact at the time of its construction. This is also consistent with the findings from the so-called residential city excavation within the wall, in which the building density decreased in the course of the 3rd century, but public buildings such as baths, the water supply and stores and workshops for the supply of the population were still in operation in the 4th century.

While the construction of the late Roman defensive structure on the city hill indicates a temporary decline in population at the end of the Roman Imperial period, which also seems to be evident in the C14 dated skeletal finds from Pergamon, it did not mean the end of the unfortified lower city in the medium term. Thus, the sanctuary of the Red Hall was transformed into the largest church in Pergamon as late as the 5th century. For this purpose, after a severe fire, the main building of the sanctuary was rebuilt into a three-nave basilica with a polygonally encased apsis, which was most likely the Episcopal Church of Pergamon.

Excavations in previously unexplored areas to the east and south-east of the Red Hall are now providing further insights into late Roman and early Byzantine Pergamon. In 2021, the Pergamon Excavation was given the opportunity to investigate a peristyle building with floor mosaics to the south-east of the Red Hall, which had been partially uncovered during excavations by the Bergama Museum. This year, it was possible to further investigate the extent of the building and its spatial arrangement (Fig. 3. 4). Not only were the boundaries of the building determined on two other sides, but a presumed bathroom and other rooms with mosaic floors were also found. Excavation trenches in layers from the construction period suggest a dating to the 4th century at the earliest. The size of the building with a length of more than 40 meters and the numerous rooms decorated with mosaic floors indicate that it was either a residence of the urban elite or the residence of a dignitary.

Fig. 4 (right) Mosaic House, aerial picture

Not far to the west of the peristyle building, on the other side of the Türbe Mezarlik, excavations carried out in preparation for meliorative measures along the Selinus river revealed a number of smaller buildings and rooms and numerous canals and clay pipes as well as a road carved into the rock (Fig. 5. 6). We were also able to document these important findings. Judging by the initial findings of our investigations, these are late Antique to early Byzantine workshops. Perhaps they were used for dyeing or tanning, which were deliberately located downstream from the city in order to pollute the water only after it had passed the city. Tanneries were still located here until the 20th century.

With this new knowledge, several findings fit together in the picture of Late Antique-Early Byzantine Pergamon: The building activities in the Red Hall, the construction of the peristyle house, and the craft activities along the river show that the lower city of Pergamon could hardly have been in decline in the 4th/5th century. Further archaeological, historical and paleoanthropological investigations, including new results on environmental history, will show whether the idea of a temporary crisis in the late 3rd century can be confirmed, which would then have been followed by a renewed flourishing period in the 4th-5th century.

A testimony to the religious life of this period has been provided by a clay pilgrim bottle from the excavation in the Mosaic House, showing St. George and probably St. Polycarp, Bishop of Smyrna (Fig. 7). It represents an interesting addition to the cult of local martyrs such as Antipas, to whom the above-mentioned church in the Red Hall was probably dedicated.

Fig. 7 (right) Pilgrim bottle found in Mosaic House excavation