—

by Berslan Korkut and Berglind Hatje

During the 2023 survey, the team of the TransPergMicro project focused on the eastern part of the Pergamon Micro-Region, which had received less attention in the past compared to its western counterpart (see Lost and Found in an Altered Landscape). The re-discovery of long-forgotten aqueduct remains prompted fresh questions and ideas. This exceptional landscape, intertwined with water, offers a stimulating insight into what humans (including administrations) would do to exploit and manage water in both ancient and modern times.

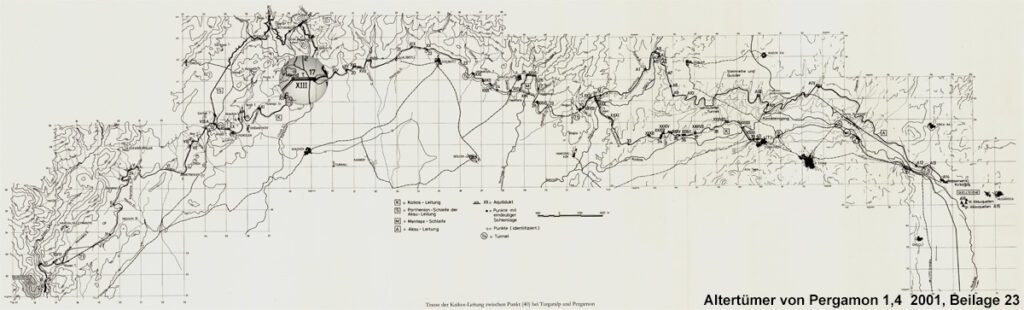

Archaeologists’ interest in the area has a long history. In the 1880s, early researchers of Pergamon explored ancient remains in the area, among which two stood out. Firstly, the so-called Paşa Ilıcası, a thermal bath from the 2nd century CE, still impressively well-preserved with its pool retaining running thermal water (Fig. 1). Secondly, although perhaps less impressive at first sight, were the remnants of the Karkassos Aqueduct (Fig. 2). The latter attracted significant focus in 1887 and subsequently in 1893, when Friedrich Gräber reported on a Roman water pipeline connected to an aqueduct in the upper Kaikos valley. The Karkassos Aqueduct is one of approximately 40 aqueducts forming the 50 km long Kaikos-waterline (Fig. 3). This waterline was a new addition, likely one of the costliest, to Pergamon’s complex water supply network first established in the 2nd century BCE (see New Insights and Questions on the Water Supply System of the Ancient City of Pergamon). The new showpiece of the water supply system is fed from a spring located approximately 40 km east of Pergamon in the modern town of Turgutalp Soma (Manisa).

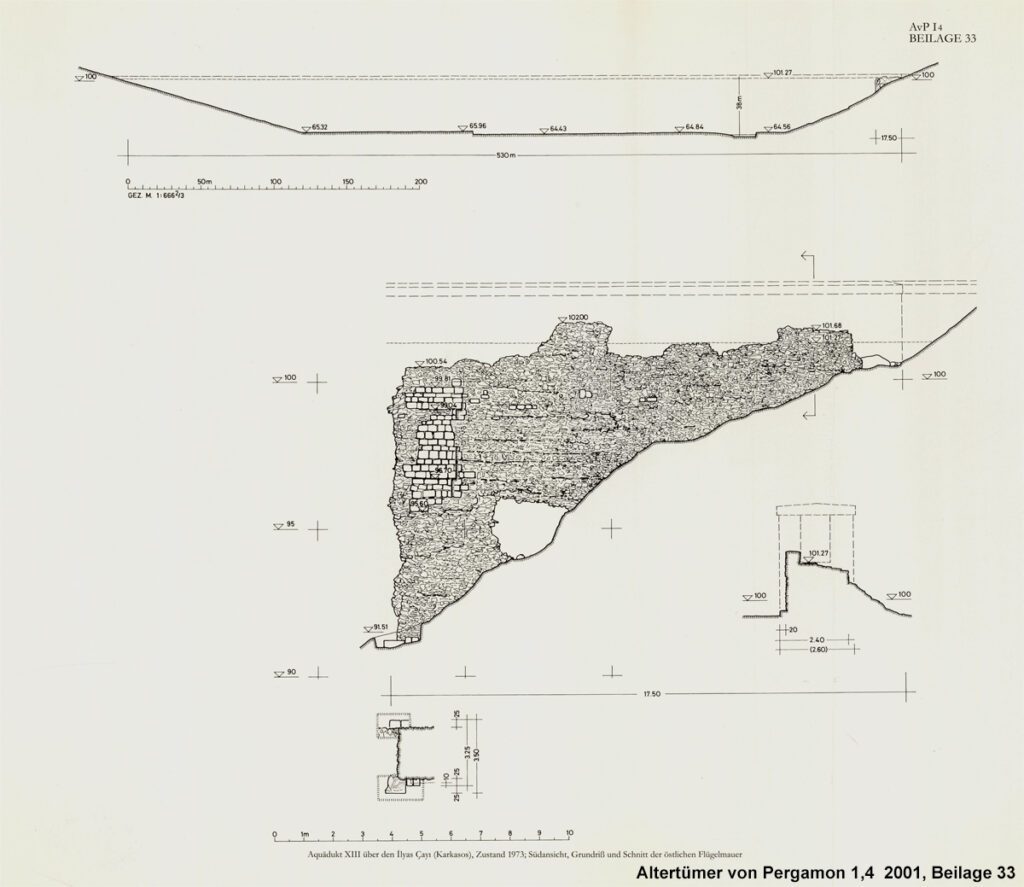

The remains today are situated about 40 meters above the valley and the Ilya River. The preserved part of the aqueduct is approximately 9 meters high and 17.5 meters long. It was constructed with two shells made of trachyte blocks, with rubble stones in a lime mortar mixture filling the space between them. The aqueduct is 4.5 meters wide at the bottom and 3.5 meters wide at the top, sloping upwards with two recesses to support the structure. At the eastern end of the wall, the channel sole is preserved, consisting of a 5 cm thick layer of brick fragments with lime mortar.

Based on their observations and other aqueducts on the same waterline, early researchers put forward a reconstruction idea. Given the 550-meter distance between the remains and the hill on the other side of the valley, they estimated this aqueduct to measure 550 meters in length and 40 meters in height, making it one of the largest aqueducts of the ancient world (Fig. 4). Dating the aqueduct, however, presents a certain challenge. Unfortunately, there are no references to the aqueduct in written sources. Since Pliny the Elder (23-79 CE) considers the Aqua Claudia and Aqua Anio Novus to be the largest structures, the aqueduct of the Kaikos-waterline must have been built later. This assumption is supported by the measurements given by Frontinus (35-103 CE) stating that the Anio Nova was “only” 33 m high. In the 1970s, research continued under the direction of Günther Garbrecht. In cooperation with the Lichtweiss Institute for Hydraulic Engineering of Braunschweig, he documented the water management systems of ancient Pergamon. The publication of his studies in 2001 (AvP I4) also marked the last mention of the Karkassos aqueduct. Nonetheless, Garbrecht’s investigations provide important clues for dating: Based on the analysis of sinter, the aqueduct was in use for about 60 years. The deposit also bore witness to two significant events in the later phase of use when soil washed into the pipe, which could indicate an earthquake or a flood event. One of the well-known recorded earthquakes in the period was an earthquake in Smyrna in 165 CE, which dates the construction of the aqueduct more precisely to the Traianic-Hadrianic period at the beginning of the 2nd century CE, aligning with the substantial building program observed in the lower city of Pergamon (see The Amphitheater of Pergamon and Research at the so-called Lower Western Gymnasion of Pergamon).

Today, the riverbed spanned by the aqueduct is almost completely dry. However, wall blocks several hundred meters away, which can clearly be attributed to the aqueduct, show that this river once had a strong stream (Fig. 5). Since the previous investigations of the aqueduct in the late 19th and late 20th centuries, two dams (Yortanlı and Çaltıkoru) have been built for irrigation purposes in the immediate vicinity, leading to some alterations in the landscape as evidenced by the dried-up riverbed once flowing under the Karkassos Aqueduct.

The construction of these dams not only dried up the Ilya River but also impacted the landscape significantly. One of the most substantial landscape alterations took place in the eastern part of the Pergamon Micro-Region (also see Lost and Found in an Altered Landscape). The modern landscape in the Kaikos plain to the east of Pergamon is almost completely flat, resulting from leveling the uneven, wet, and non-arable lands to make them suitable for farming and channeling water for agricultural use. Some of these leveled areas include archaeological sites once called “…tepe” (…hill), now completely flat with scattered archaeological finds on the surface. The construction plans of these dams, especially Yortanlı, faced a public outcry after the exploration of archaeological remains in the reservoir. Building it meant submerging the archaeological site of Allianoi, which contained various monuments of cultural heritage: the aforementioned Paşa Ilıcası, bridges, latrines, public and residential buildings, as well as pottery, glass and metal production workshops, and many more. Despite the public opposition, the dam was built, resulting in Allianoi’s submergence by the dam’s waters. The construction of the Çaltıkoru Dam also directly affected some remains of cultural heritage, including aqueducts: As a direct consequence of the plans for landscape and building development, the blocks of the aqueduct were dismantled and relocated a few hundred meters away from the dam.

In essence, the dams were built to boost agricultural productivity in the Kaikos Plain (Bakırçay Vadisi). Along with the damage to the cultural heritage, however, the unintended consequences were felt greatly by the villages adjacent to the dams. Now lacking access to irrigation water living by the dams, these villages faced profound challenges. The change in climatic conditions and increasing numbers of mosquitos due to stagnant water made villages less attractive, leading to their abandonment or the relocation of their population to the plain and Bergama. Today, various dams serve as vital sources of irrigation water for the fertile lands of the Kaikos Plain, facilitating the cultivation of staple crops such as corn, cotton, tomatoes, and wheat.

Constructing ancient waterlines and modern dams were and are integral components of administrative and state-building programs aimed at ensuring a consistent water supply for various purposes, including agriculture, production, construction, and drinking. These initiatives likely stem from a common concern: the ever-growing demands resulting from population growth, which in turn intensifies the need for water, food, and products, thus perpetuating a vicious cycle of increasing population and resource consumption.

Ultimately, the case of the past and present Pergamon Micro-Region serves as a compelling reminder of the intertwined relationship between humans and water, crucial not only for the resilience of settlements but also as a timeless phenomenon echoing throughout human history.

– – –