Göbekli Tepe is situated on the highest point of the Germuş mountain range in southeastern Turkey. The spot is hostile to settlement; the next accessible springs are located in a distance of about 5 km northeast (Edene) and to the southeast (Germuş). A number of pits at Göbekli Tepe’s western slope could represent cisterns to collect rain water; although their exact date could not have been determined yet. With a total capacity of 153,12 cubic metres (cf. Herrmann-Schmidt 2012) they may have accumulated enough water for people to stay there for a longer periods of time, but probably not during the whole rainless summer. The next Neolithic settlements so far known were found in the plain in immediate vicinity of nearby springs, like for example Urfa-Yeni Yol.

From its discovery onwards, the interpretation of Göbekli Tepe’s suprising architecture has centered around the terms ‘special purpose buildings’ (Sondergebäude), ‘sanctuaries’, or even ‘temples’. Naturally, this line of interpretation has been called into question. As already discussed here, it is indeed quite challenging to use a rather strictly defined historical terminology and complex spiritual concepts to describe the material remains of prehistoric phenomena. Even more while cult, ritual and ultimately religion are concepts often cited but rarely clearly defined by archaeologists.

Just recently a colleague challenged the existence of pure domestic or ritual structures for the Neolithic, arguing that archaeologists tend to impose modern western distinctions of sacred vs. profane on prehistory, while anthropology in most cases shows these two spheres to be inseparably interwoven (Banning 2011, 624-627). In his eyes, Göbekli Tepe rather was a settlement with buildings rich in symbolism, but nevertheless domestic in nature. Undisputedly, this boundary is perceived much stricter today after centuries of secularization in the western hemisphere, although it should be noted that this differentiation indeed also is known from non-western societies, too. Banning’s arguments that in-house inhumations, caches and wall paintings are demonstrating that ‘the sacred’ clearly is leaking into everyday live in the Near Eastern Neolithic (Banning 2011, 627-629) and that therefore a clear distinction is impossible to define, is valid, too, of course. In fact the idea of manifestations of the sacred in houses or parts of houses is neither new, nor surprising as already M. Eliade pointed out in his seminal work on the entanglement of the sacred and profane. Yet Eliade also emphasized that belief and faith of course could focus within special places and structures particularly dedicated to give ‘the sacred’ a room: “… the sanctuary – the center par excellence was there, close to [man], in the city, and he could be sure of communicating with the world of the gods by entering the temple.” (Eliade 1959, 43). All this is essentially theoretical thinking, based on historical sources and ethnologic observation. But going back to prehistoric periods which are denying such direct access, we are thrown back again at a selection of what is left physically and intentionally – exclusively. In case of the enclosures unearthed at Göbekli Tepe this means to focus on the material culture found in this context and the structures themselves.

Pillar 31, one of the central pillars of Enclosure D, illustrates the anthropomorphic appearance of the T-shaped pillars due to the depiction of arms, hands, and a loincloth. (Photo: N. Becker, DAI)

Among these, still the monumental T-shaped pillars can be regarded as the site’s most prominent and most defining moment. While they remain faceless, the depiction of arms, hands, and clothing clearly identifies these up to 5.5 m high pillars as anthropomorphic, but distinctively also larger than life at the same time. Their highly abstracted character must be considered intentional, in particular since we know of the existence of more naturalistic and life-sized sculptures like for example the contemporaneous ‘Urfa man’ and numerous heads of similar sculptures discovered at Göbekli Tepe. So, even though we cannot know if these buildings actually were really meant to house gods or deities, the peculiar role of these larger-than-life anthropomorphic images forming the centre and main element of the enclosures at Göbekli Tepe remain conspiciously disctinctive to the life-sized sculpture heads which were apparently carefully deposited in the backfill.

- So-called Urfa Man is considered the oldest known life-sized sculpture of a man (Photo: J. Notroff, DAI).

- Limestone head from Göbekli Tepe, supposedly part of a sculpture similar to ‘Urfa Man’ (Photo: N. Becker, DAI).

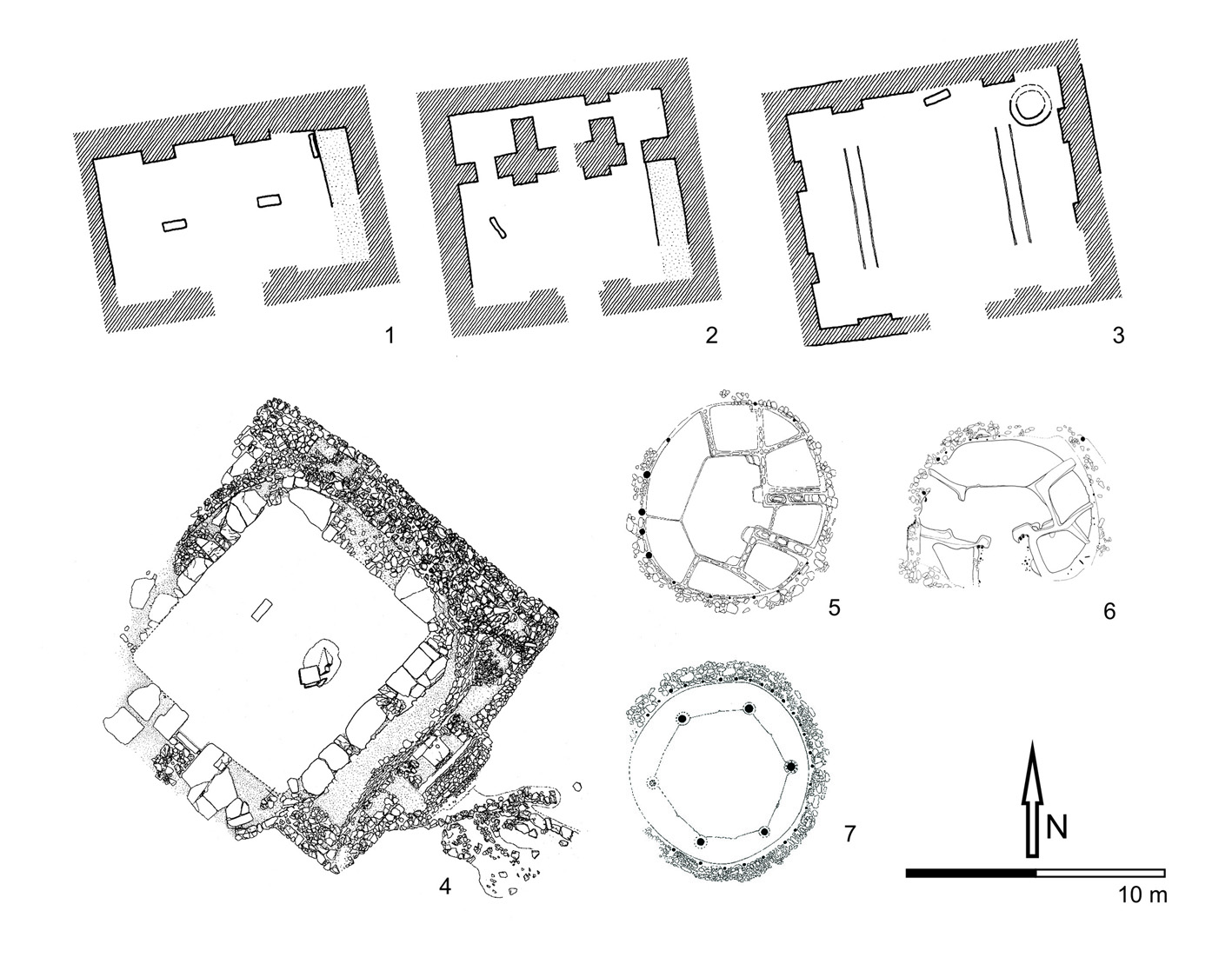

Early Neolithic domestic architecture is well known in the upper Euphrates region due to the long and secure stratigraphy of rectangular buildings at Çayönü Tepesi (Schirmer 1988; 1990; Özdoğan 1999) and extensive excavations at Nevalı Çori (Hauptmann 1988) for instance, both stiuated in Turkey. Contemporaneous with Göbekli Tepe in this sequence would be Çayönü’s so-called grillplan-phase (PPNA), the ‘channeled’ ground plans (early PPNB; attested also in Nevalı Çori), and the ‘cobble paved buildings’ (middle PPNB). Research of the last 20 years in the region has revealed that almost every settlement site of the 10th and 9th millennium BC, which was excavated more extensively, shows a spatial distinction into living quarters and workshop areas and furthermore produced special buildings or free spaces for apparently communal or ritual activity. Characteristic traits of these so-called special purpose buildings are benches at the inner walls, rich and elaborate inner fittings as well as outstanding installations and finds like (stone) sculptures and sometimes human burials – as the examples of Nevalı Çori’s ‘Terrazzo Building’, Çayönü’s ‘Skull’, ‘Terrazzo’ and ‘Flagstone Buildings’ or the communal buildings at Jerf el Ahmar and Mureybet (northern Syria) demonstrate, to just name some.

‘Special purpose buildings’ of the PPN: 1. Çayönü, ‘Flagstone Building’ (after Schirmer 1983, fig. 11c), 2. Çayönü, ‘Skull Building’ (after Schirmer 1983, fig. 11b), 3. Çayönü, ‘Terrazzo Building’ (after Schirmer 1983, fig. 11a), 4. Nevalı Çori (after Hauptmann 1993, fig. 9), 5. Jerf el Ahmar (after Stordeur et al. 2000, fig. 9), 6. Mureybet (after Stordeur et al. 2000, fig. 2), 7. Jerf el Ahmar (after Stordeur et al. 2000, fig. 5).

Reconstruction of the ‘Terrazzo Building’ at Nevalı Çori where T-Pillars were found for the first time. (Photo: H. Hauptmann, reconstruction: N. Becker, DAI.)

At Göbekli Tepe no traces of this well-documented typical domestic PPN architecture could have been proven as of yet. But the existing structures at the site clearly mirror features and layout of those outstanding communal ‘special purpose’ buildings which usually are the exception within settlements. At Göbekli Tepe, however, this building type is not an exception, but the general rule – almost overrepresented compared to other settlement sites, while whole object classes (like clay figurines for instance) known from these settlements are almost completely absent.

Summing up, from our point of view there seems to be ample evidence to interpret Göbekli Tepe as a peculiar place formed of special purpose structures related to cult and ritual with distinct and fixed life-cycles of building, use, deconstruction and burial. All of these stages seem to be marked by specific ritual acts, of which the last, i.e. those related to burial and deposition of symbolic objects are naturally best visible in the archaeological record. What remains is largely a problem of adequate terminology to address these buildings and the site as a whole. If ‘temple’ is understood as a technical term for specialized cult architecture, one could indeed consider this lable for Göbekli Tepe. If the term is defined in our western perception as a place where a god is present, maybe ‘sanctuary’’ would be a more neutral description; alternatively the auxiliary construction of ‘special purpose buildings’ (Sondergebäude) may be used to escape any trap of culturally bound denominations. But in any case one thing is sure: the idea that Göbekli Tepe’s buildings are “so fair a house” seems not the most convincing interpretation of the available evidence so far.

A more detailed discussion of this question can be found in:

O. Dietrich and J. Notroff, A sanctuary, or so fair a house? In defense of an archaeology of cult at Pre-Pottery Neolithic Göbekli Tepe. In: N. Lanerie (ed.), Defining the Sacred. Approaches to the Archaeology of Religion in the Near East. Oxford & Philadelphia: Oxbow 2015, 75-89.

References:

E. E. Banning, So Fair a House: Göbekli Tepe and the Identification of Temples in the Pre-Pottery Neolithic of the Near East, Current Anthropology 52/5, 2011, 619-660.

M. Eliade, The Sacred and the Profane. New York: Brace & World 1959.

H. Hauptmann, Nevalı Cori: Architektur, Anatolica XV, 1988, 99-110.

H. Hauptmann, Ein Kultgebäude in Nevalı Cori. In: M. Frangipane, H. Hauptmann, M. Liverani, P. Matthiae and M. Mellink (eds.), Between the Rivers and Over the Mountains. Archaeologica Anatolica et Mesopotamica Alba Palmieri dedicata. Rome: Università di Roma “La Sapienza”, 37-69.

R. A. Herrmann and K. Schmidt, Göbekli Tepe – Untersuchungen zur Gewinnung und Nutzung von Wasser im Bereich des steinzeitlichen Bergheiligtums. In: F. Klimscha, R. Eichmann, C. Schuler and H. Fahlbusch (eds.), Wasserwirtschaftliche Innovationen im archäologischen Kontext. Rahden/Westf.: Verlag Marie Leidorf GmbH, 2012, 57-67.

A. Özdoğan, Çayönü. In: M. Özdoğan and N. Başgelen (eds.), Neolithic in Turkey. Istanbul: Arkeoloji ve Sanat Yayınları, 1999, 35-63.

W. Schirmer, Zu den Bauten des Çayönü Tepesi, Anatolica XV, 1988, 139-159.

W. Schirmer, Some Aspects of Building at the ‘Aceramic Neolithic’ Settlement of Çayönü Tepesi, Wolrd Archeology 21/3, 1990, 363-378.

D. Stordeur, M. Brenet, G. der Aprahamian and J. C. Roux, Les bâtiments communautaires de Jerf el Ahmar et Mureybet horizon PPN A (Syrie), Paleórient 26/1, 2000, 29-44.

I agree that the best interpretation of PPNA Tepe Gobekli is that it did not serve a domestic function, and most importantly, that the pillars did not support roofs. Given the poor water supply, it is hard to imagine that whole families would have spent the whole summer there. Given the harsh winters, it is hard to believe that the people would have built roofed domestic structures with such high ceilings, as such buildings would have been very hard to heat. The absence of hearths within the enclosures also argues against the “so fair a house” hypothesis. It also doesn’t make sense that the people would have chosen to build structures with log/thatch roofs (a la Banning, 2011) on the highest point for miles around, as such buildings would have been especially prone to lightning strikes. Baird, in his defense of Banning (2011), stated that roofs would have been necessary to maintain the walls, but the only advantage of a roof would have been to protect the wall mortar better by keeping the rain off. The people could have actively maintained the wall mortar without roofs.

Reblogged this on Voices and Visions.

In the first paragraph you state “the next accessible springs are located in a distance of about 5 km northeast (Edene)”.

I have searched several resources and cannot find a spring or other location by that name.

Can I get more details?

Edene Köyü is a village circa 5 km northeast of Sanliurfa.

This is the most comprehensive publication on water at Göbekli Tepe: Richard A. Herrmann, Klaus Schmidt, Göbekli Tepe – Untersuchungen zur Gewinnung und Nutzung von Wasser im Bereich des steinzeitlichen Bergheiligtums, in: Florian Klimscha – Ricardo Eichmann – Christof Schuler – Henning Fahlbusch (Hrsg.), Wasserwirtschaftliche Innovationen im archäologischen Kontext. Von den prähistorischen Anfängen bis zu den Metropolen der Antike. Menschen – Kulturen – Traditionen. Studien aus den Forschungsclustern des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts. Band 5. Forschungscluster 2. Innovationen: technisch, sozial. (2012) 57-67.

Many thanks, Oliver and Jens. I will try to acquire the publication, and run it through Google Translate. My German consists of knowing the word “gesundheit”.

Oliver.dietrich(at)dainst.de. Drop me a mail, I‘ll send it to you.