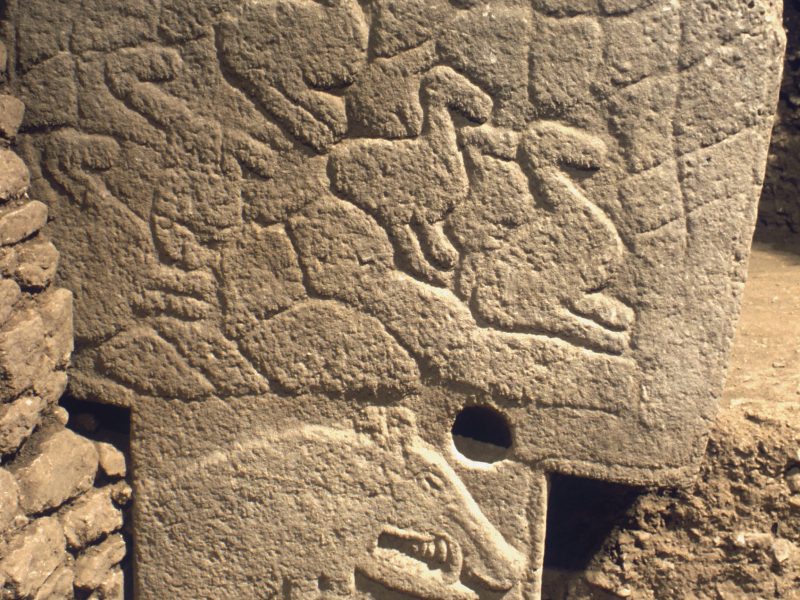

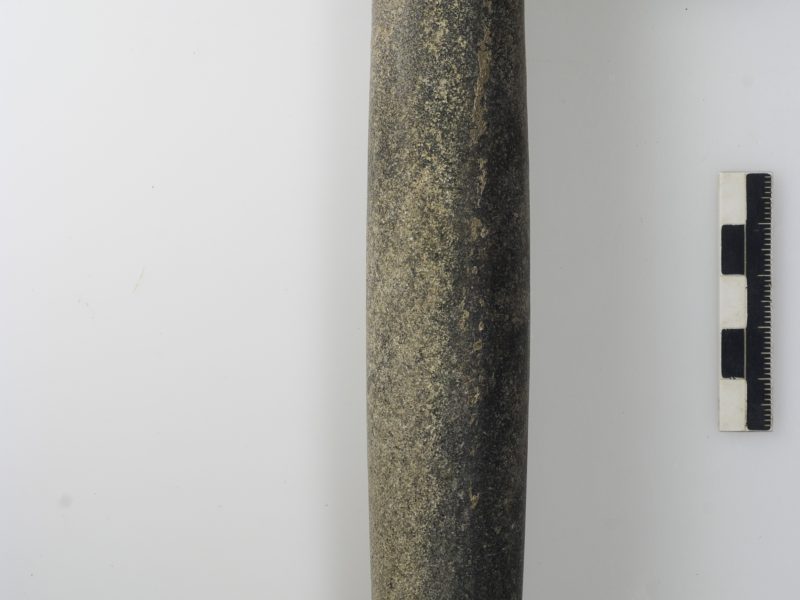

- Pillar 12 in Enclosure C (Photo D. Johannes, copyright DAI).

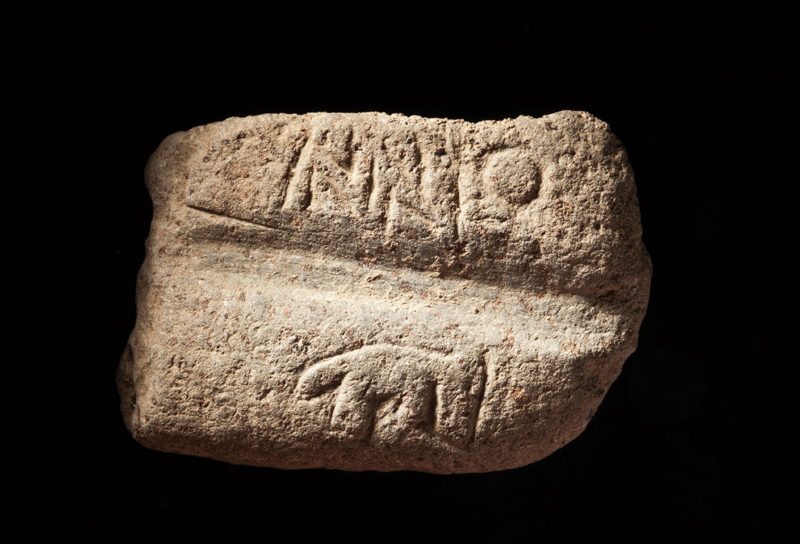

- Sculpture of a boar next to Pillar 12 in Enclosure C (Photo D. Johannes, copyright DAI).

Depictions and sculptures of boars predominate the imagery of Enclosure C. Pillar 12 for example has a very nice depiction of a boar with pronounced canine teeth. Next to this depiction a sculpture of a boar was found, obviously deposited there during refilling. Another deposition of a boar sculpture, this time together with stone plates, was found next to one of Enclosure C´s central pillars. The list continues with many further examples, as most boar sculptures discovered at Göbekli Tepe are from Enclosure C. The richness of both boar depictions and sculptures hints at a special concern of the builders of that stone circle with wild boar. As other enclosures also feature a dominant animal species, there is the possibility that we are dealing with emblematic or totemic animals here. But not all of the depictions are just “emblematic” in character. It seems that some, or all, also tell a story.

In an earlier post [link], I have shortly reviewed the possibility of narrative elements in Göbekli Tepe´s iconography with regard to snake depictions. For example, on the front side of Pillar 20 in Enclosure D we see a snake moving towards an aurochs. The aurochs´ body is seen from the side, the head from above. The position of the head, lowered for attack, could be in futile defence to the snake. The aurochs´ legs are depicted oddly flexed, which could indicate his defeat and near death. As could the size of the snake which is depicted considerable larger than the aurochs.

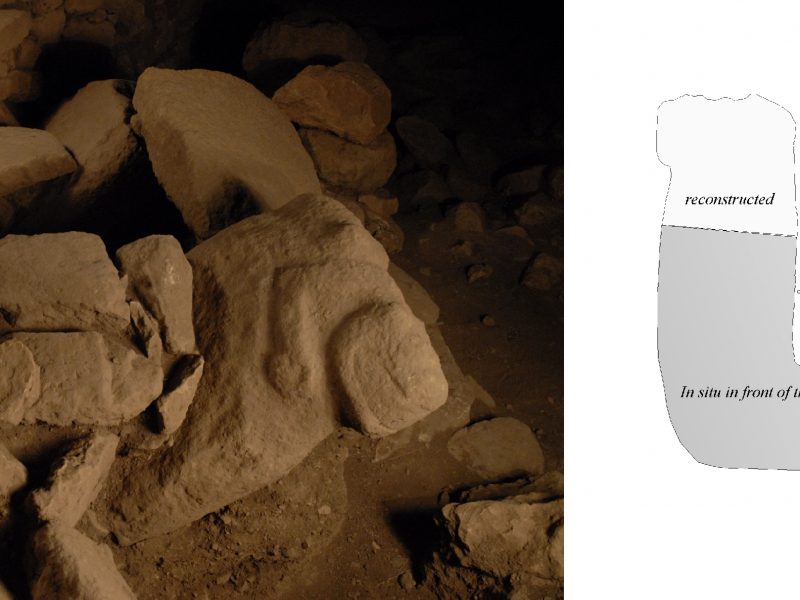

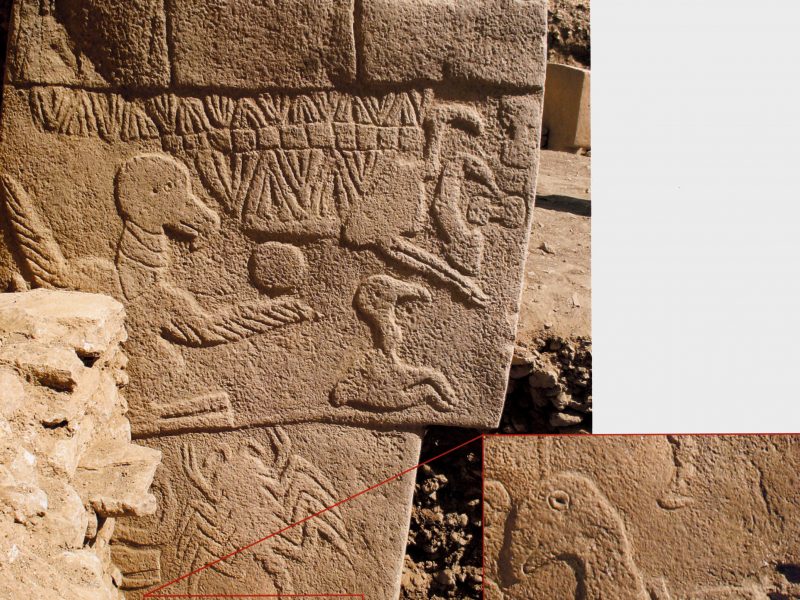

- Pillar 27 in Enclosure C (Photo D. Johannes, copyright DAI).

- Pillar 27 in Enclosure C, detail of predator in high relief and boar in low relief (Photo D. Johannes, copyright DAI).

Another pair of animals to which that kind of metaphoric “reading” might apply is boars and snarling predators. Both are depicted frequently at Göbekli Tepe, and in a highly standardized way. One cannot help to note the emphasis the depictions put on the dangerous parts of these animals, especially their teeth. Of special interest for an understanding of at least one aspect of the meaning of this imagery is Pillar 27 in Enclosure C. On its shaft there is a high relief of a predator moving downwards. Both, animal and pillar are made of one piece. Below the predator, a much smaller depiction of a boar was added in flat relief. The choice of different techniques for the images may not be coincidental. The small boar appears to be lying on the side, the predator moving towards it. One possible interpretation would be – again – a hunting scene, with the boar possibly depicted already dead.

- Plan of Enclosure C with entrance situation, stairway possibly leading to “dromos” (Photo N. Becker, plan K. Schmidt with modifications by J. Notroff, copyright DAI).

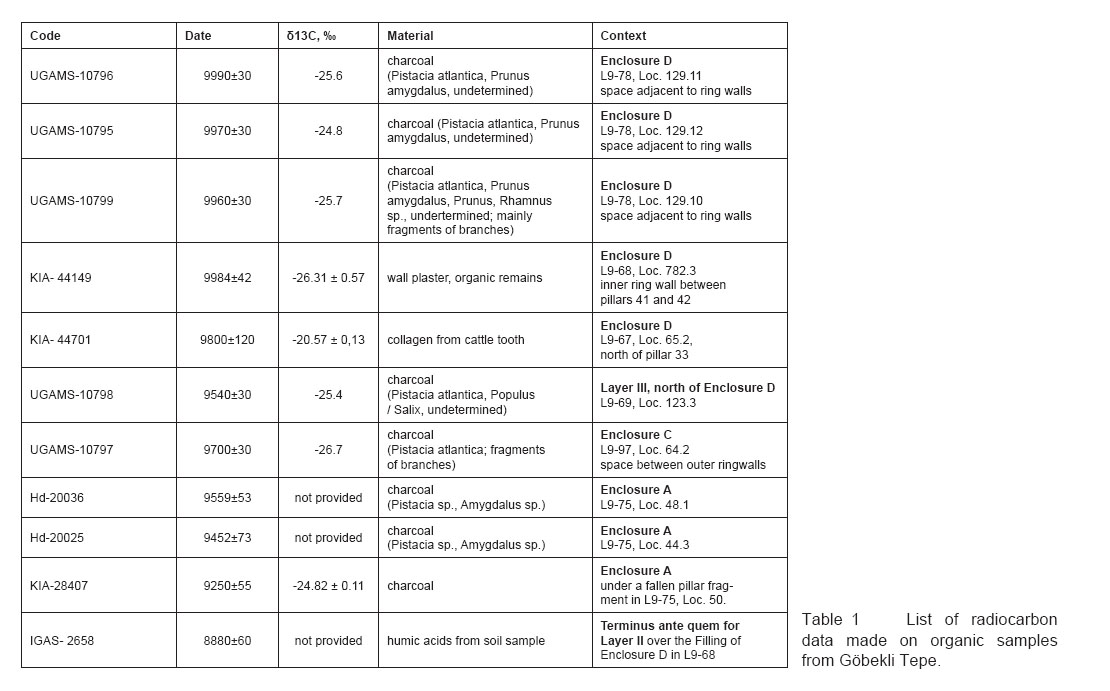

- U-stone at the entrance of Enclosure C (Photo D. Johannes, drawing K. Schmidt, copyright DAI).

- Porthole stone behind the U-stone at the entrance to Enclosure C (Photo D. Johannes, copyright DAI).

At this point, another aspect of Enclosure C has to be mentioned. It is the only enclosure so far, where at least for one building phase a clear entrance situation (later blocked by a wall) could be discovered. The supposed entrance way is formed by two walls branching off almost rectangularly towards the south and running nearly parallel to each other. The walls are made of conspicuously huge stones which are worked on all sides. Like a barrier, a huge stone slab protrudes into this passage. The slab has not been completely preserved, however it is safe to say that once it had been provided with a central opening closed by a stone setting, of which two layers are still preserved. At the southern side of the slab, looking away from Enclosure C and towards the visitor, there is a relief of a boar lying on its back below the opening of the door hole. The reliefed porthole stone is accompanied by another building element. At first, in front of the porthole stone, the plastically carved sculpture of a strong beast of prey with a wide open mouth could be recognized. Whether it is a lion or a bear cannot be decided. Only 80cm away, we found a similar counterpart whose probably sculptured head, however, had been severed and is lost. When the excavation went on it became obvious that the second, eastern column, together with the western counterpart, belonged to one gigantic, monolithic, U-shaped object. Obviously, together with the porthole slab, it marked the entrance of Enclosure C.

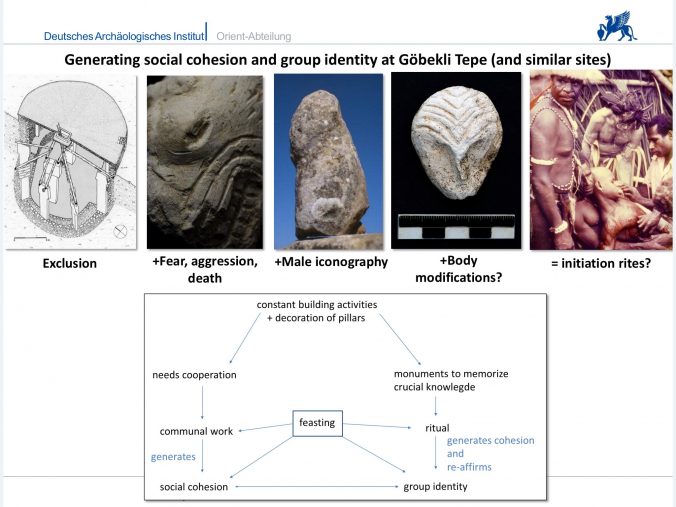

So the scenery of Pillar 27 is somehow repeated at the very entrance of the stone circle. Not only are a boar in flat relief and three dimensional predators shown, this time the boar also lies on its back. But what could be the meaning of this? Or, more directly put, why would you portray an animal presumably important to your group’s identity in an unfortunate condition? Some explanation might come from the predators here. They are often also portrayed in unfavourable conditions with their ribs clearly sticking out, as also on Pillar 27. Images of that sort are known from other contexts and sites in the Near Eastern Neolithic and beyond. They could reflect a dual symbolism of life and death, the interaction and correlation of both principles. This would fit with the general character of the enclosures. Their use-lifes included burial, the treatment of human imagery found inside them shows close relations to death ritual [link], as do finds of skull fragments with cut marks inside the filling. Symbolic death and rebirth are important features of rites of passage, as for example initiation ceremonies. The imagery could thus open up a path towards a deeper understanding of the functions of Göbekli Tepe´s enclosures.

Food for future thought, definitely.

Further reading

Klaus Schmidt, Die steinzeitlichen Heiligtümer am Göbekli Tepe, in: Doğan-Alparslan, Meltem – Metin Alparslan – Hasan Peker – Y. Gürkan Ergin (Hrsg.), Institutum Turcicum Scientiae Antiquitatis – Türk Eskiçağ Bilimleri Enstitüsü. Colloquium Anatolicum – Anadolu Sohbetleeri VII, 2008. 59-85.

Klaus Schmidt, Göbekli Tepe, Southeastern Turkey. A Preliminary Report on the 1995-1999 Excavations, Paléorient 26/1, 2001, 45-54.

Joris Peters, Klaus Schmidt, Animals in the Symbolic World of Pre-pottery Neolithic Göbekli Tepe, South-eastern Turkey: a Preliminary Assessment, Anthropozoologica 39.1,2004, 179-218.

Jens Notroff, Oliver Dietrich, Klaus Schmidt, Gathering of the Dead? The Early Neolithic sanctuaries of Göbekli Tepe, Southeastern Turkey, in: Colin Renfrew, Michael Boyd and Iain Morley (Hrsg.), Death shall have no Dominion: The Archaeology of Mortality and Immortality – A Worldwide Perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (2016), 65-81.

Oliver Dietrich, Çiğdem Köksal-Schmidt, Cihat Kürkçüoğlu, Jens Notroff, Klaus Schmidt, Göbekli Tepe. A Stairway to the circle of boars, Actual Archaeology Magazine Spring 2013, 30-31.

On half-skeletonized animals

Hodder, I. & L. Meskell, 2011. A “Curious and Sometimes a Trifle Macabre Artistry”. Current Anthropology 52(2), 235-63.

Huth, C., 2008. Darstellungen halb skelettierter Menschen im Neolithikum und Chalkolithikum der Alten Welt. Archäologisches Korrespondenzblatt 38, 493-504.

Schmidt, K, 2013. Von Knochenmännern und anderen Gerippen: Zur Ikonographie halb- und vollskelettierter Tiere und Menschen in der prähistorischen Kunst, in: Sven Feldmann – Thorsten Uthmeier (Hrsg.), Gedankenschleifen. Gedenkschrift für Wolfgang Weißmüller, Erlanger Studien zur prähistorischen Archäologie 1, 195-201.

Recent Comments