Just back from this year´s Warfare, Environment, Social Inequality and Peace Studies (WESIPS) Conference in Seville, organized by Richard and Yamilette Chacon at the Center for Cross-Cultural Study (Spanish Studies Abroad). After a very inspirational conference and a stay in a very nice city, I thought I´d share a (very) short version of my talk. So here it comes.

The last post-Ice Age hunter-gatherer communities of the Near East have long been seen as loosely organized and low-hierarchical. The last decades of research have revealed a number of sites which considerably change this image. Nearly every site excavated at the appropriate scale shows a spatial division of residential and specialised workshop areas, and special buildings or open courtyards for communal and ritual purposes. Thus there is strong evidence for a degree of social complexity that was hitherto quite unsuspected.

While there is continued dispute over the question of organized warfare in the earliest Neolithic of the Near East, recent research has provided clear evidence of inter-personal and probably inter-group violence and beginning social inequality. But there are also signs of evolving strategies for conflict mitigation and cooperation. A key site to understand this aspect of early Neolithic social practises is Göbekli Tepe, a mountain sanctuary in southeastern Turkey.

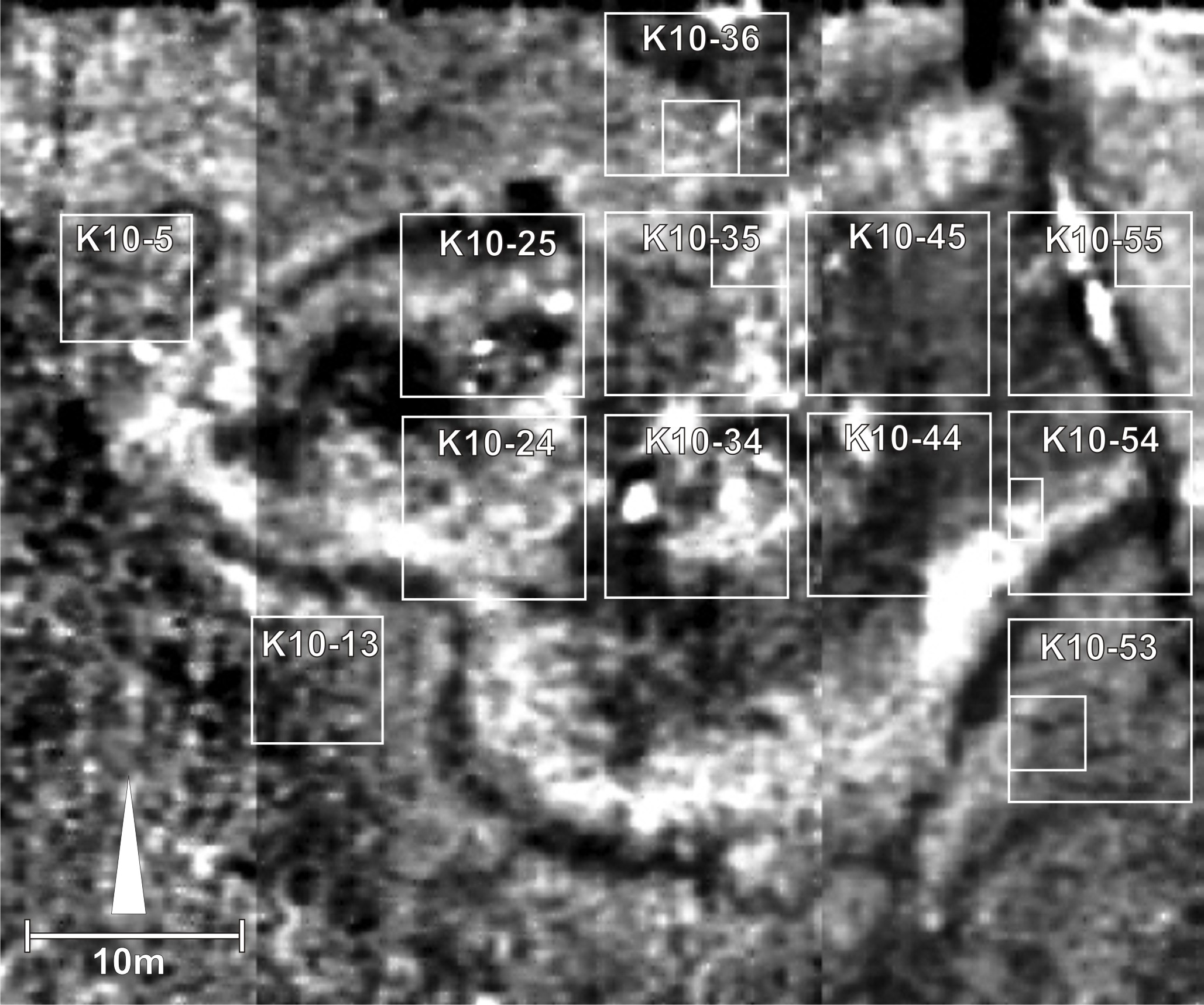

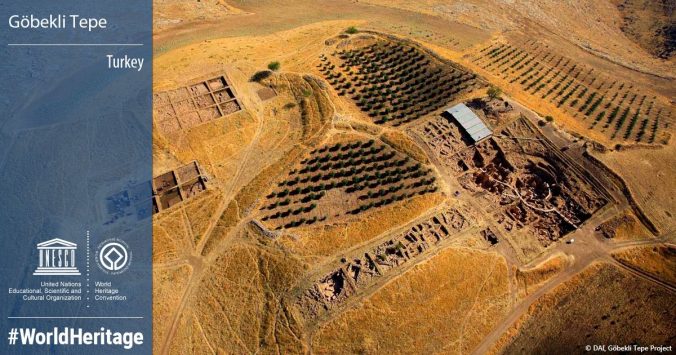

Göbekli Tepe is situated on the highest point of the Germuş mountain range overlooking the Harran plain. The site lies on an otherwise barren limestone plateau. The tell has a diameter of around 300 m and is characterized by several mounds divided by depressions. At the highest point, Göbekli Tepe has about 15 m of stratigraphy. Work at the site started in 1995 under the direction of Klaus Schmidt and concentrated in the first ten years in the southeastern depression. Starting from 2007 further excavation areas were opened on the soutwestern and nortwestern hilltop, and in the northwestern depression.

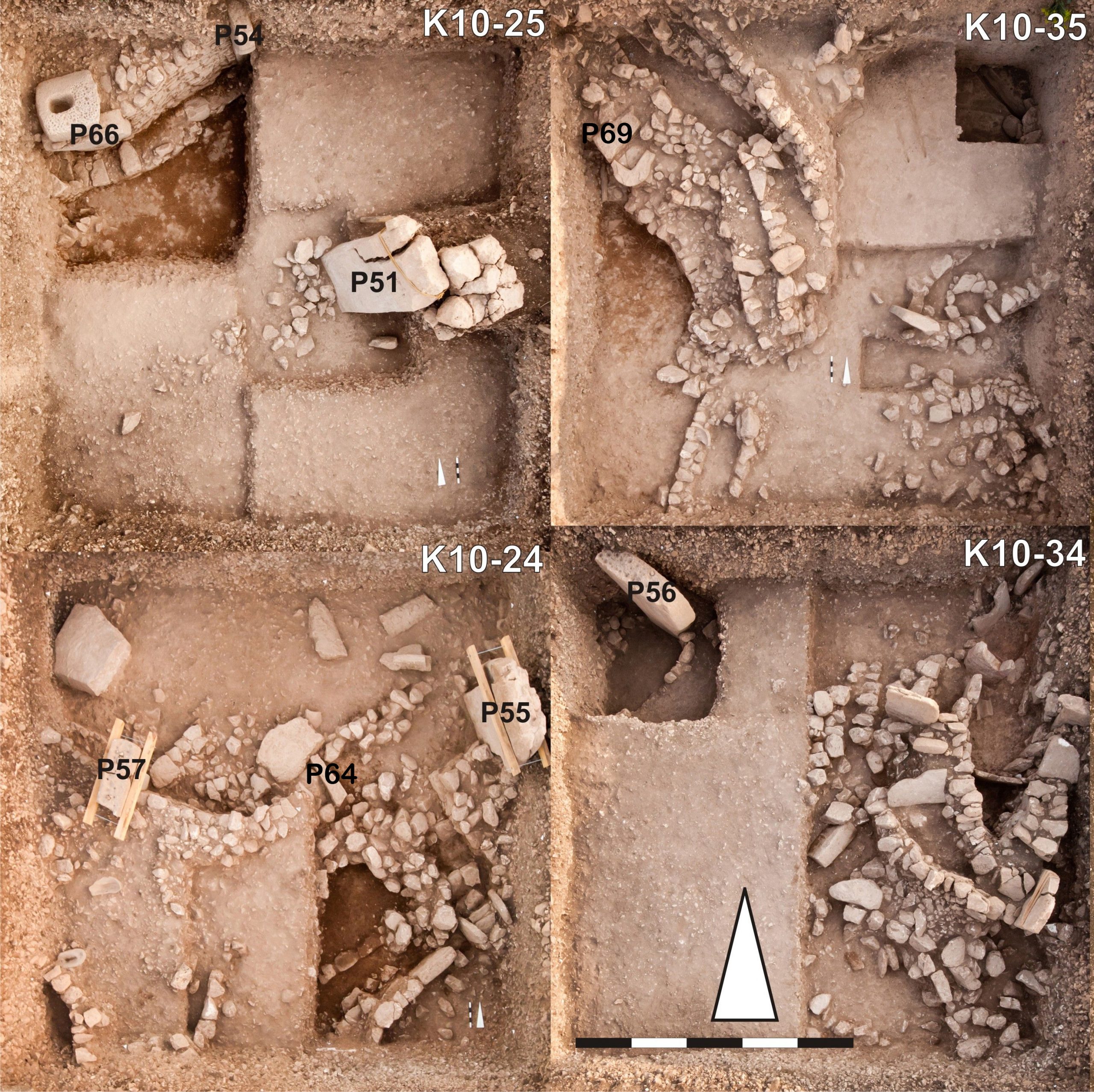

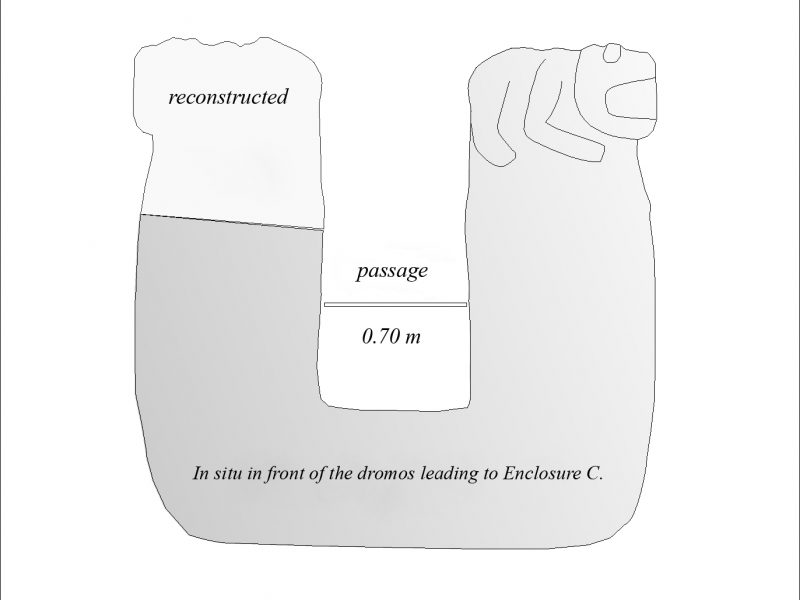

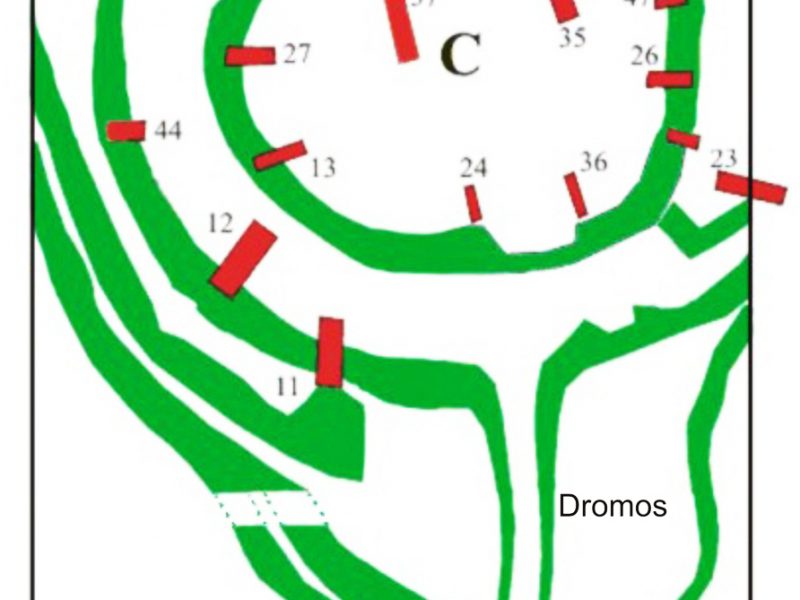

All areas excavated so far show a similar general stratigraphic sequence. The oldest layer III is characterized by monolithic T-shaped pillars, which were positioned in circle-like structures. The pillars were interconnected by limestone walls and benches leaning at the inner side of the walls. In the centre of these enclosures there are always two bigger pillars, with a height of over 5m. The circles measure 10-20m. This layer dates to the Pre-Pottery Neolithic A and maybe reaches the earliest PPN B, between 9600-8800 in absolute dates. The buildings of layer III were intentionally beckfilled at the end of their uselifes. Layer III is supraposed by layer II, dating to the early and middle PPNB, the time between 8800-8000 cal BC. This layer is characterised by smaller, rectangular buildings. The number and the height of the pillars are also reduced.

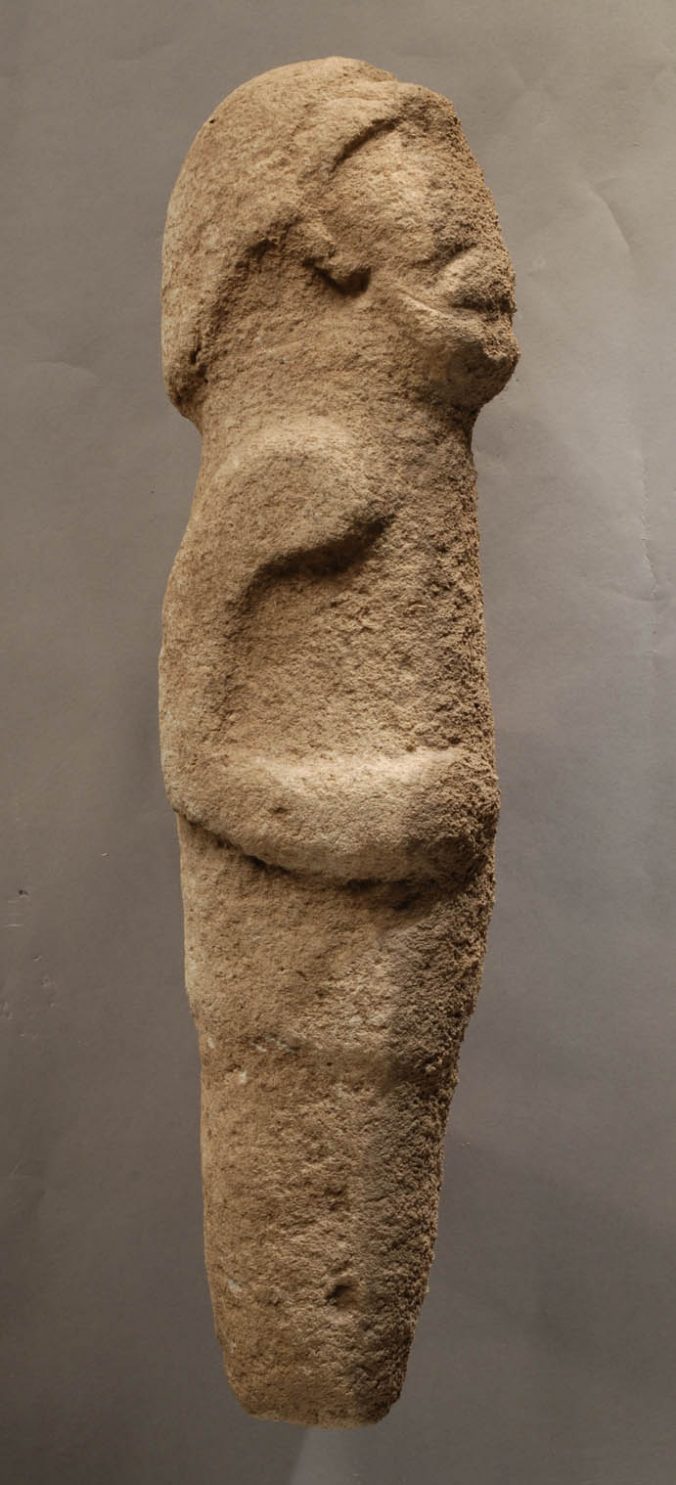

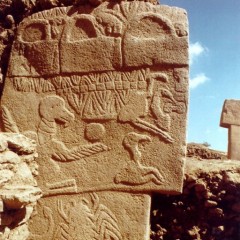

The most impressive element of Göbekli Tepe´s architecture are the T-shaped pillars. The T-shape is clearly an abstract depiction of the human body seen from the side. Evidence for this interpretation are the low relief depictions of arms, hands and items of clothing like belts and loinclothes on some of the central pillars. There is a clear hierarchy of pillars inside the enclosures. The central pillars are up to 5,5 m high, they have the already described anthropomorphic elements. The surrounding pillars are smaller, but more richly decorated with animal reliefs than the central ones. They are always „looking“ towards the central pillars, and the benches between them further amplify the impression of a gathering of some sort. The input of work in the constructions seems enormous.

At Göbekli Tepe, the Neolithic quarry areas are well known. They lie on the limestone plateau immediately adjacent to the site. The maximum distances that had to be covered were 600-700m. However, the terrain is uneven and sloping upwards, and the megaliths are of impressive size. The input of manpower seems pretty high.

And another aspect is of importance. It seems that the enclosures were never really finished. There is permanent construction, deconstruction, and reconstruction activity at Göbekli Tepe, and the intensity of work indicates something else than pure maintenance. Most likely the act of working at the site was central to the builders, and repeated periodically, whether or not a real need existed. For example, in the inner ring of Enclosure C there is barely one pillar standing in its original position.

As Göbekli Tepe has no traces of settlement, there is no possibility of a direct evaluation of the number of people present on-site. If we turn to ethnographic data, core group sizes of 25-50 persons for fully mobile hunter-gatherers, and a little higher numbers for semi-sedentary residential groups are suggested. The number of people one group could spare for construction work of the amplitude visible at Göbekli Tepe is definitely too small. It seems possible that several groups had to collaborate for a period of time to carry out building activities and to supply for the builders. And there actually is vast evidence for people congregating at Göbekli Tepe.

An answer to the question why these people congregated for work at Göbekli Tepe comes from the enclosure´s fillings. The material used as backfill consists of limestone rubble from the quarries nearby, flint artefacts and animal bones smashed to get to the marrow, clearly the remains of meals. Enclosure D alone, the largest of the four circles, comprised nearly 500 cubic meters of debris. As traces of permanent settlement are absent, this readily leads to the idea of large, ritualized work feasts rooted in the belief systems of the people congregating there. This concept was explored in-depth by Dietler and Hayden and provides a good working hypothesis to explain the at least temporary supra-group cohesion generated for collective work.

Archaeozoological data further strengthens the image of large feasting events at certain times of the year. At Göbekli, Gazelle is the major meat animal [external link]. As this species is migratory, a large scale supply of meat was possible in late autumn, when there would also be rain water available after the long, dry summer. The second important species is aurochs, an animal all year round available in the meadows surrounding the Germus mountains. A single auerochs can provide enough meat for a smaller group of people. Of course both sources could have been used supplimentarily. But why hunt dangerous aurochs when there is an abundance of Gazelle? It seems more likely, that aurochs was targeted at occasions different from the work feasts, and maybe more related to the enclosures´ functions which seem to be related to distinct groups of people.

The enclosures excavated so far show a variation in the animal species depicted prominently in the iconography of each circle. While in Enclosure A the snake prevails, in Enclosure B foxes are dominant, for example. In Enclosure C boars take over and in Enclosure D birds are playing an important role, while Enclosure H has lots of wildcats. Interpreting these differences as figurative expression of community patterns could probably hint at the different groups building the particular enclosures. The character of these entities remains open to discussion at the moment. There are some clues however. Restriction of the access to knowledge and participation in rituals seems to be attestable at Göbekli Tepe. On a general level, some object classes known from settlements are missing. For example, awls and points of bone are nearly completely absent. The tasks carried out with them probably were not practiced here, and it may well be that the part of the population carrying them out was absent, too. Further, clay figurines are absent completely from Göbekli. This observation gains importance in comparison to Nevalı Çori, where clay figurines are abundant, missing only in the ‘cult building’ with its stone sculptures and T-shaped pillars very similar to Göbekli Tepe. Clay and stone sculptures may thus well form two different functional groups, one connected to domestic space (and cult?) and one to the specialized ‘cult buildings’ – and to another sphere of ritual also evident at Göbekli Tepe. Its iconography is exclusively male.

The pillars are often richly decorated. But in some cases, the imagery obviously is going far beyond mere decoration. The narrative character of several depictions in flat relief is underlined by Pillar 43, whose whole western broad side is covered by a variety of motifs. This could be a hint to one aspect of the enclosure´s functions – as a repository for tales, maybe myths crucially important to the groups building them. It is also possible to identify the general theme these stories – and the enclosures – are related to. A recurring motif on reliefs is human heads between animals, or, as already seen on pillar 43, headless humans. The special treatment and the removal of skulls is well-attested for the PPN death ritual. A connection with death or ancestor cult of Neolithic groups seems to be the most probable function of Göbekli Tepe´s enclosures. With their rich decoration, they are monuments in stone of important aspects of these groups´ identities, which were reinforced during ritually repeated events that included feasting.

To conclude, it seems that at Göbekli Tepe we see several social phenomena interact. Religious belief generated a need for constant costly building activity, which could only be accomplished by cooperation, possibly of members of different groups. Cooperation was ensured by large work feasts, that produced social cohesion. These groups reinforced their identities through – most likely – unpleasant initiation rituals held within the circular buildings. The character of these groups, marked by emblematic animals and important aspects of mythology carved and preserved in stone, remains unclear at the moment. Clans or tribes would be a possibility, but also other organizational structures, that cross-cut those based on ancestry are a distinct possibility. As only male hunters become visible at Göbekli Tepe, and exclusion as well as initiation seem to have played a major role, secret societies are another possibility. Festing and ritual thus emerge as major incentives for cooperative action during the earliest Neolithic.

Further reading

Some points of this talk have already been discussed more extensively here:

Oliver Dietrich, Jens Notroff, A sanctuary, or so fair a house? In defense of an archaeology of cult at Pre-Pottery Neolithic Göbekli Tepe. In: Nicola Laneri (eds.), Defining the Sacred: Approaches to the Archaeology of Religion in the Near East. Oxford: Oxbow (2015), 75-89.

Oliver Dietrich, Jens Notroff, Klaus Schmidt, Feasting, Social Complexity and the Emergence of the Early Neolithic of Upper Mesopotamia: A View from Göbekli Tepe, in: R. J. Chacon and R. G. Mendoza (eds.), Feast, Famine or Fighting? Multiple Pathways to Social Complexity. Studies in Human Ecology and Adaptation 8, New York: Springer (2017), 91-132.

Jens Notroff, Oliver Dietrich, Klaus Schmidt, Gathering of the Dead? The Early Neolithic sanctuaries of Göbekli Tepe, Southeastern Turkey, in: Colin Renfrew, Michael Boyd and Iain Morley (Hrsg.), Death shall have no Dominion: The Archaeology of Mortality and Immortality – A Worldwide Perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (2016), 65-81.

On the possibility of secret societies in the Neolithic:

Brian Hayden, Corporate Groups and Secret Societies in the Early Neolithic. A Comment on Hodder and Meskell. Current Anthropology 53, 1, 2012, 126-127.

On gazelle at Göbekli Tepe:

And, on feasting in archaeological contexts:

Dietler, Michael and Brian Hayden (editors) (2001). Feasts: Archaeological and Ethnographic Perspectives on Food, Politics, and Power. Washington, DC: Smithsonian.

Recent Comments