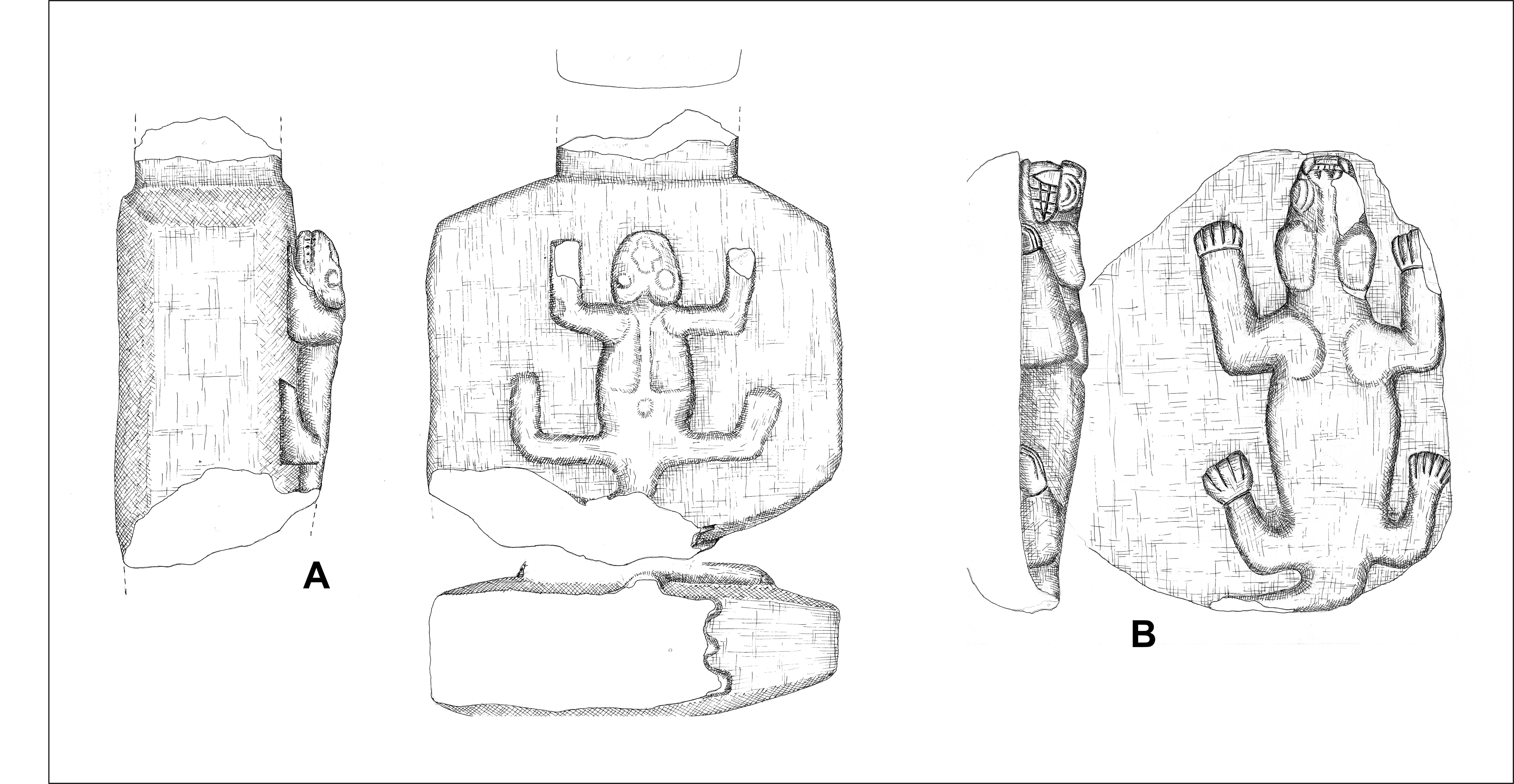

In 2011, a special object was discovered at Göbekli Tepe in one of the excavation trenches in the tell’s northwestern depression (Fig. 1). Excavation had just proceeded into layers undisturbed by modern ploughing, but there were still no traces of architecture, when a fragment of a bone object was found. The artefact was described preliminarily as a ‘spatula’ made from a rib bone. It measures 5.3 x 1.9 x 0.3 cm and bears a carved drawing that is only partly preserved. The image is rather unclear, however in the upper part, two hatched T-shaped forms are visible – one completely preserved, the other one only fragmentarily. These T-shapes rapidly led to associations with Göbekli Tepe’s most prominent architectural feature, and to a vivid discussion within the research team focusing on the probability of this interpretation and our possibilities of understanding Neolithic ‘art’ in general.

Fig. 1: Bone ‘spatula’ from Göbekli Tepe (Photo: N. Becker, DAI, ).

The problems of interpretation prevented a premature publication of the find. Meanwhile it went on display in the Şanlıurfa Museum. As the interaction of museum visitors with the small object evolved largely along the same lines as ours in 2011 and has also evolved in more speculative directions [external link], it seems important to get back in more detail to the question of the ‘readability’ of this Neolithic depiction.

There is an ongoing discussion about the possibilities and pitfalls of interpreting art in archaeology. One aspect of this debate is the potential use of iconological approaches. Between the most influential models is Erwin Panofsky’s concept that he presented in the 1930s (1934, reprinted in 1982). He described “three strata of subject matter or meaning” (Panofsky 1982: 28, 40-41), e.g. levels of inference on the intentions and messages encoded in images by the artist. The first level of meaning is the “primary or natural subject matter”, the perception of basic forms as representations of natural objects, e.g. humans, animals, plants or inanimate objects and their spatial setting or possible interactions. On this level, interpretation in Panofsky’s view does not reach beyond the natural meaning of things; it is a basic pre-iconographical description that can be reached without further cultural knowledge. On the second level, basic motifs are combined and identified with cultural-specific themes or concepts (Panofsky 1982: 29-30). Panofsky’s most often cited example for this stratum is to recognize a group of persons seated at a dinner table in a certain arrangement as a representation of the last supper. This iconographical interpretation or understanding needs additional information. If one lacks the acculturation in a society for which these topics are understandable, written sources or other means of information are needed for a correct interpretation. The third level of interpretation, the iconology, targets the “intrinsic meaning or content”, i.e. the intentions of the artist in displaying an image just in that way, the messages he wanted to send about his subject, or the historical and political context in which the work was made. The iconological analysis thus tries to elucidate the symbolic values of images. In Panofsky’s (1982: 41) words, what is needed to achieve this is “synthetic intuition, a familiarity with the essential tendencies of the human mind, conditioned by personal psychology and Weltanschauung“. And of course all the insights gained from interpretation levels 1 and 2.

That in mind, the difficulties in reading and interpreting prehistoric art become obvious. As soon as such depictions cross the line to abstraction and symbolism, familiarity with their proper cultural context and knowledge of their connotations is inevitably necessary to perceive and understand theses codes. In particular, this includes us today. Without the cultural intimacy with narratives and concepts linked to these depictions and symbols we could at best guess what is a) depicted and b) meant. Unfortunately this offers a large probability of misconception. Somehow like discovering the symbol of the cross in a Christian church, yet without any clue to the whole Passion narrative it stands for and which is perceived without further explanation by members of most occidental cultures and even beyond. To be useful for Prehistoric Archaeology, Panofsky’s thoughts have to be adapted to the specific sources of this discipline. The need for a broad understanding of the cultural setting of images for an iconographical analysis (level 2) is a requirement hard to fulfil completely, when only material remains are available without written sources. But to some extent, this lack can be compensated for by find contexts on a macro (site-) and micro (deposition-) level and analogical reasoning. Panofsky’s model has the potential to address the ‘readability’ of an image as a key factor for a successful analysis. It thus seems appropriate to analyse the possibilities of understanding an ambiguous prehistoric depiction like the one on the ‘spatula’ from Göbekli Tepe.

(The impossibility of) Pre-Iconography

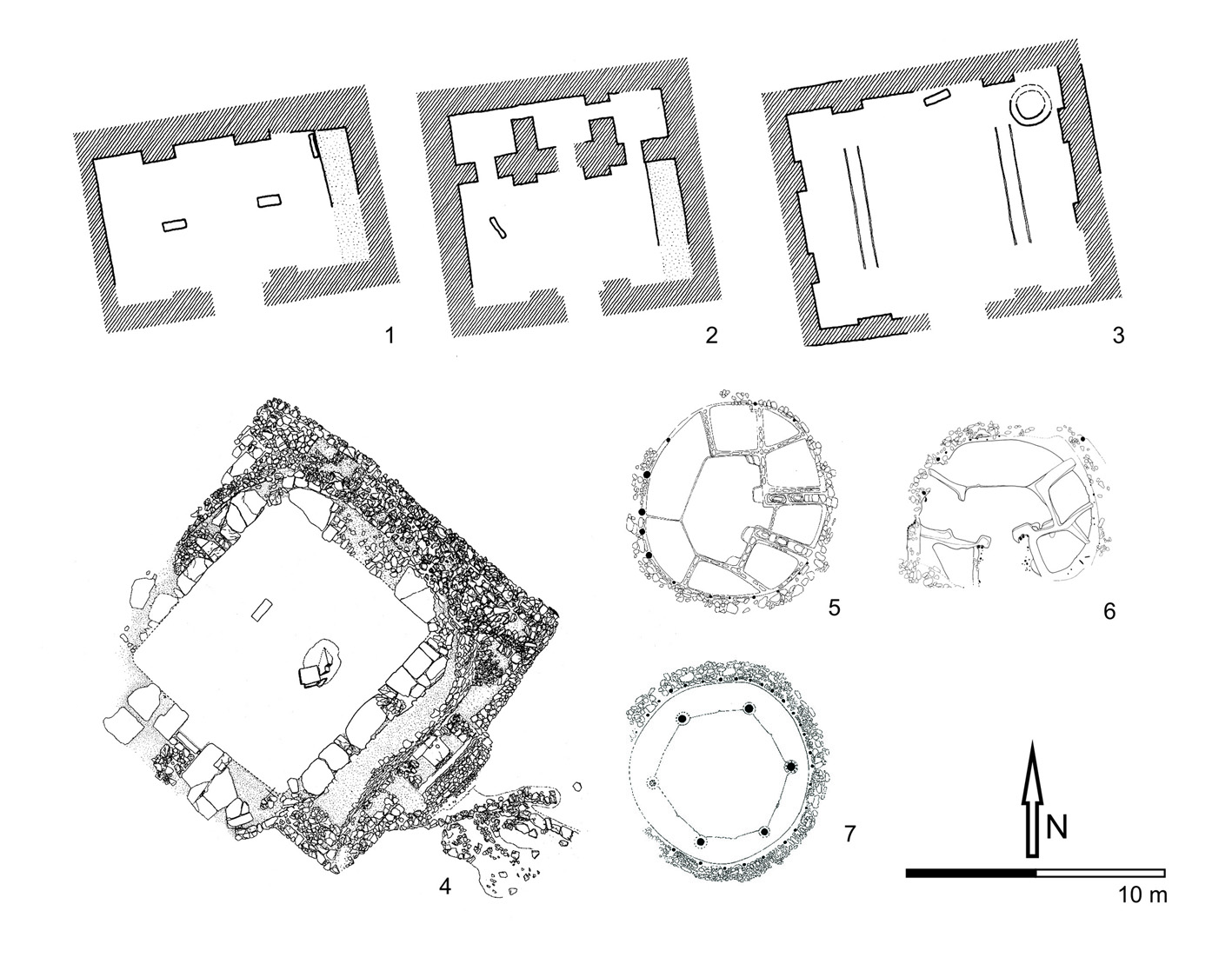

So, let’s just try to describe/understand what is represented on our spatula. Some colleagues from the moment of its discovery were convinced that the T-shaped objects on the spatula must be representations of the iconic find category of Göbekli Tepe’s archaeological record: the T-shaped pillars. In this line of thought, a roughly human shaped figure was standing in front of the pillars, while in the bottom left corner of the spatula the enclosure walls were represented.

There are some problems with this interpretation however. The perspective of the depiction is not easily understandable, as inside the real enclosures the central pillars stand side by side, not facing each other. This may find an explanation in the artist’s intention to display the T-shape of the pillars, which was obviously important to Göbekli Tepe’s builders. Furthermore, one of the visible ‘pillar shafts’ is depicted very slender, curved and narrowing in the lower part. An explanation for this could lie in the abilities of the artist to depict a perspective view, or it was not important to them to show these details in a realistic manner. It is rather difficult to explain however that the pillars, the presumed walls, and the potential human are interconnected by lines. At Göbekli Tepe, animals and humans are normally depicted individually, not interwoven. Yet there is another important point regarding the mode of depiction on this bone spatula. If we are really confronted with a depiction of the enclosure walls, they would very much look like the modern, excavated state. Today, the walls end considerably below the pillars. Whether this was the prehistoric appearance of the enclosures remains unclear for the moment; there is the possibility to reconstruct the buildings as semi-subterranean and roofed structures. In this case, the depictions of very small walls would not make much sense.

And there is another way of understanding the depiction. The people who built Göbekli Tepe had a very distinct concept of depicting their world. On reliefs, animals were usually represented in the way humans see them during a real-life confrontation. Snakes, spiders, and centipedes were thus depicted in flat relief and from above; larger animals like wild cats, foxes, gazelle etc. are shown from the side. A very interesting exception from this rule is associated with depictions of cattle. The body of aurochs is depicted in side elevation, the head however is seen from above. The special way of depicting the aurochs’ head could have a distinct meaning. It is fairly possible that the animal is shown with its head lowered for an attack, the sight a hunter sees in the moment the animal speeds towards him (read more here). Notably, the cattle head is one of the few animal depictions also transformed into a possible ideogram at Göbekli Tepe. Bucrania can be found on several pillars and other elements of architecture (like so-called porthole stones). It is obvious that the mode of representing animals in Neolithic art is far from arbitrary. Starting from here, another interpretation of the spatula appears possible.

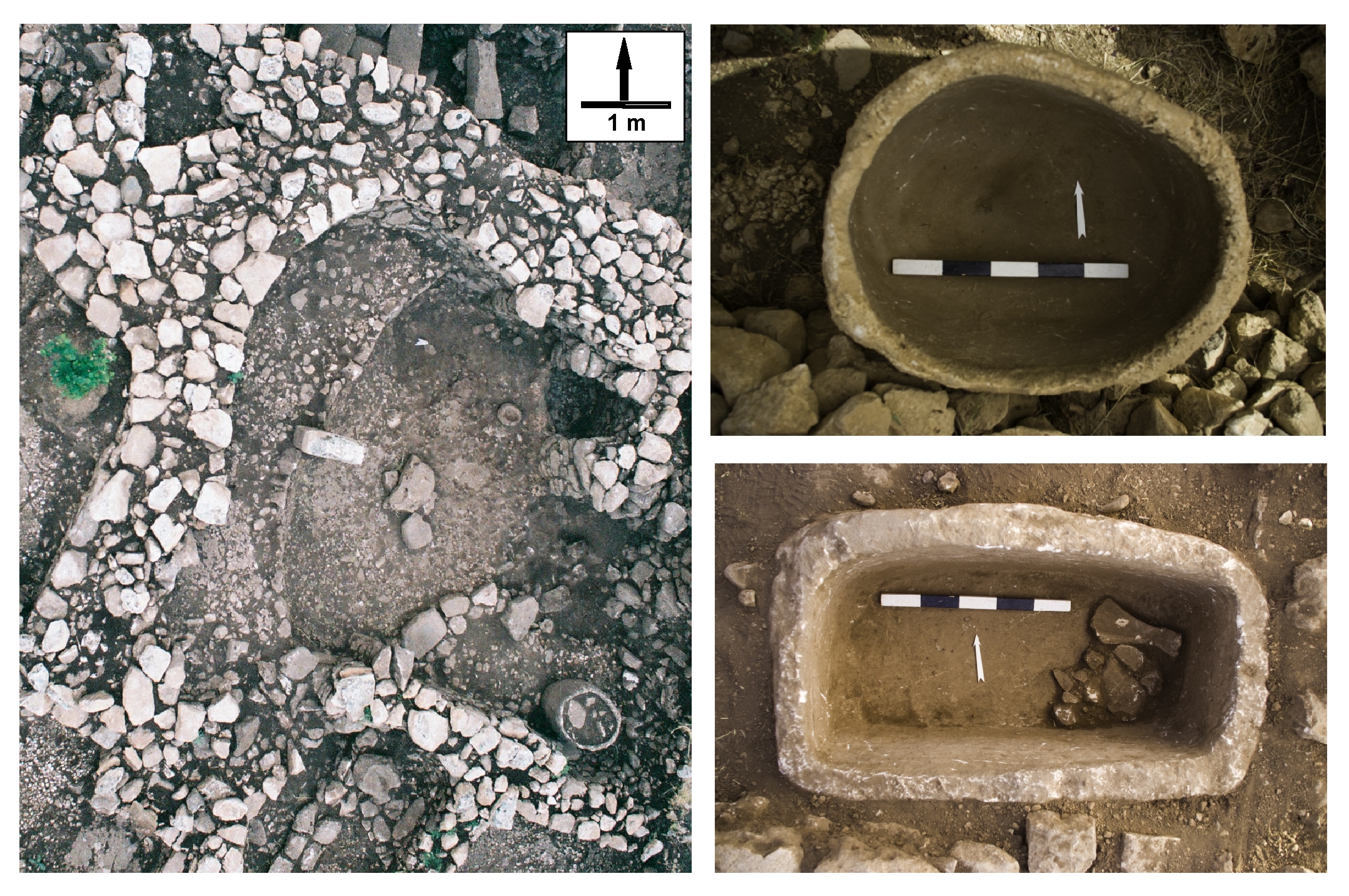

Fig. 2: Depictions of animals with stretched out limbs from Göbekli Tepe (Drawings: K. Schmidt, DAI).

Two larger stone slabs from Göbekli Tepe show high reliefs of animals in a crouched position, (Fig. 2) probably ready to jump; another depiction of that type can be found on the front-side of Pillar 6. The animals’ limbs lie stretched out besides head and body, a long tail is bent to one side. Schmidt (1999: 10-11, Nr. A12-13) suggested an interpretation as reptiles, while Helmer, Gourichon and Stordeur (2004: 156-157, Fig. 7) see them as felids, more exactly panthers, and compare them to depictions from Tell Abr’ 3 and Jerf el Ahmar. Meanwhile two more examples of squatted animals can be added from Göbekli Tepe, one on a fragmented stone slab, the other one on the shaft of Pillar 27 in Enclosure C [click here for images]. Irrespective of the depicted species, it is important that the special mode of showing certain types of animals is in any case not restricted to Göbekli Tepe, but a characteristic of Early Neolithic art in southwestern Asia in general.

While images of architecture are not well-attested, squatted animals are a standard-type in the repertoire of early Neolithic artists (e.g. Atakuman 2015: 769, Fig. 10 on the long history and the translation of this image type into stamp seal designs). The depiction on the bone spatula could thus represent a variant of this well-known type. This would also explain the hatching of the ‘body’, which could indicate the paws, as it is restricted exactly to these areas. One animal representation in high relief from Göbekli Tepe shares this feature, and its paws also take on a slightly trapezoid form.

Nevertheless, the image on the spatula does not fit exactly the intra- and offsite analogies presented here. Design and realization appear slightly awkward, which, as mentioned above, leads to the interpretational uncertainties. We could be dealing with an ad hoc engraving here that only superficially abides to the artistic conventions of displaying animals and at the same time overemphasizes certain aspects of the image. Maybe the artist wanted to emphazise the dangerous parts of the animal, its claws. However, a deeper understanding must fail in this case, as, to get back to the starting point and Panofsky, a clear pre-iconographical description is not possible.

Conclusion

The point of the above is not to show that Neolithic art in general is not understandable. But there must be a basic awareness of the fact that not every depiction is ‘readable’ beyond doubt, and that such depictions naturally should not be used as evidence for far-reaching interpretations. Panofsky’s thoughts can be a powerful instrument in determining the degree of interpretational potential of an image.

References

Ç. Atakuman 2015. From monuments to miniatures: emergence of stamps and related image-bearing objects during the Neolithic. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 25, 4: 759-788.

D. Helmer, D. Gourichon, and D. Stordeur 2004. À l’aube de la domestication animale. Imaginaire et symbolisme animal dans les premières sociétés néolithiques du nord du Proche-Orient. Anthropozoologica 39, 1: 143-163.

E. Panofsky 1982. Meaning in the visual arts. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

K. Schmidt 1999. Frühe Tier- und Menschenbilder vom Göbekli Tepe. Istanbuler Mitteilungen 49: 5–21.

Read the full story here:

O. Dietrich, J. Notroff 2016. A decorated bone ‘spatula’ from Göbekli Tepe. On the pitfalls of iconographical interpretations of early Neolithic art. Neo-Lithics 2/16: 22-31.

Recent Comments