This is the English version of a text published by Oliver Dietrich and Jens Notroff in the latest issue of Aktüel Arkeoloji [external link].

Our knowledge of the early Neolithic of Upper Mesopotamia has undergone dramatic changes in the last three decades. The region long held a peripheral role in research on this period. Ever since the seminal work of K. Kenyon at Jericho, the roots of food producing were sought in the Southern Levant. Not only was the traditional differentiation of the Pre-Pottery Neolithic in an earlier PPN A (c. 9600-8800 cal BC) and a later PPN B (c. 8800-7000 cal BC) devised at Jericho, but the existence of a wall and the famous tower seemed to be evidence for a strikingly early hierarchized society living in a ‘town’. The function of wall and tower have been heavily disputed later on, as has the attribution ‘town’, and the role of the Southern Levant as the core area of Neolithization.

With the influential research of L. and R. Braidwood at Jarmo, the focus of archaeological studies into the earliest Neolithic shifted to the northeast of the ‘Fertile Crescent’, or, as the Braidwoods put it, its ‘hilly flanks’. In recent years, it has become clear that the region encompassed between the middle and upper reaches of Euphrates and Tigris and the foothills of the Taurus Mountains has the potential to be a cradle of the new way of life that we call the Neolithic. The distribution areas of the wild forms of einkorn and emmer wheat, barley and the other ‘Neolithic founder crops’ overlap here, and the transition of the two wheat variants to domesticated crops has been pinpointed to this area. But it is especially one site in this region that has triggered paradigmatic changes in our views on early Neolithic society.

Göbekli Tepe

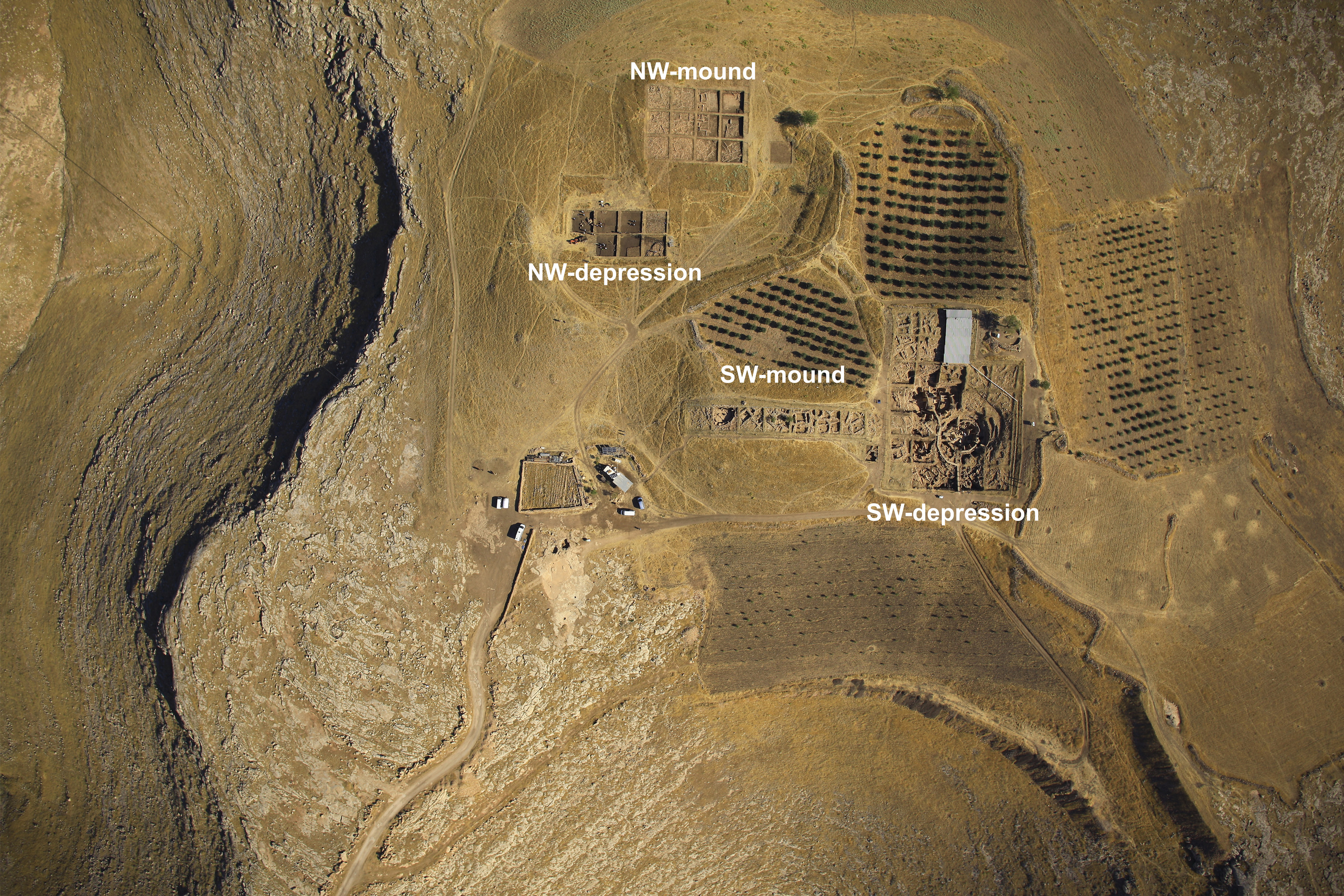

The tell of Göbekli Tepe is situated about 15 km northeast of the modern town of Şanlıurfa on the highest point of the Germuş mountain range. With a height of 15 m, the mound covers an area of about 9 ha, measuring 300 m in diameter. Neolithic artefacts were first recognized during a combined survey by the Universities of Chicago and Istanbul in the 1960s, but the architecture hidden by the mound remained unrecognized until its discovery in 1994 by Klaus Schmidt from the German Archaeological Institute. Since then annual excavation work has been conducted.

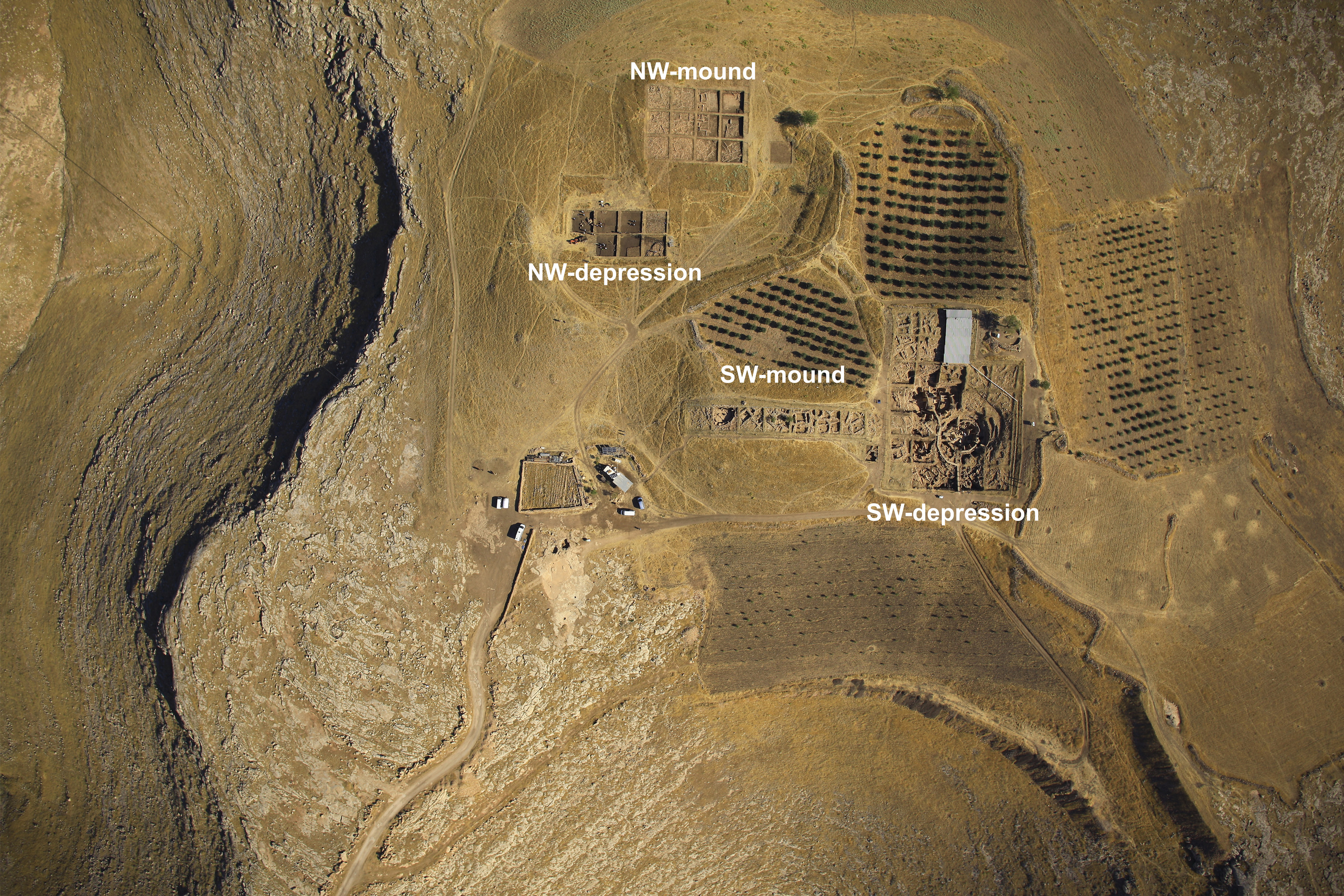

Aerial view of Göbekli Tepe (copyright DAI, Photo M. Morsch).

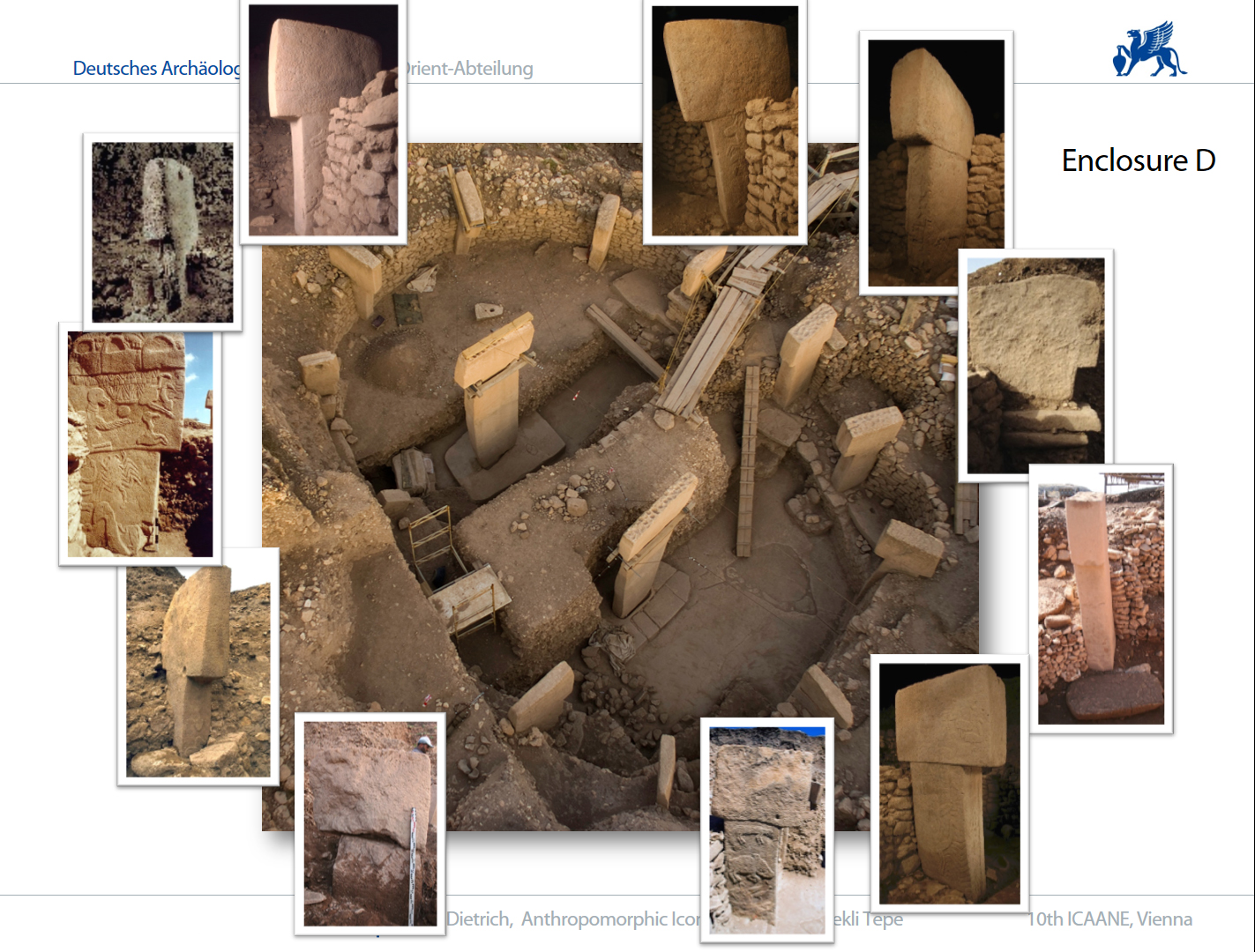

During excavation work, a rough stratigraphical schema has been established. The older Layer III with monumental architecture consisting of 10-30 m wide circles formed by huge monolithic pillars in a distinct T-shape was dated tentatively to the PPN A /early PPN B. The pillars, reaching a height of up to 4 m, are interconnected by walls and benches which define the inner and outer spaces of the enclosures. They are always orientated towards a central pair of even larger pillars of the same shape. Depictions of arms and hands on some of them indicate their anthropomorphic character. The pillars are richly decorated with reliefs showing mainly animals, and there also is a large number of limestone sculptures depicting animals and humans from the enclosures. After the end of their use, the circular buildings of Layer III were backfilled intentionally.

A younger layer is superimposed on this monumental architecture in some parts of the mound. This Layer II was dated to the early and middle PPN B. Smaller rectangular buildings of about 3 x 4 m with terrazzo floors are characteristic for this phase. They may be understood as minimized versions of the older monumental enclosures, as they share a common element – the T-shaped pillars. However, number and height of the pillars are considerably reduced: now often only two small central pillars are present, the largest among them not exceeding a height of 2 m. There are even rooms without any pillars. As with the large enclosures, no traces of domestic activities, e.g. hearths or ovens, have been detected so far. Thereafter, building activity at Göbekli Tepe seems to have come to an end. The uppermost Layer I consists of the surface soil resulting from erosion processes as well as a plough horizon.

Göbekli Tepe, overview (copyright DAI, Photo E. Kücük).

The monumental enclosures are the most impressive part of Göbekli Tepe’s archaeology. A geophysical survey, including ground-penetrating radar confirmed that these enclosures were not restricted to a specific part of the mound but existed all over the site. More than ten enclosures were located on the geophysical map in addition to the nine already under excavation – the latter designated A to I in order of their discovery. Five of these structures, A, B, C, D and G, were unearthed in the main excavation area at the mound’s southern depression; one, Enclosure F, at the southwestern hilltop; Enclosure H and I in the northwestern depression, and another one, Enclosure E, on the western plateau. Göbekli Tepe, at least in the older phase, is thus no domestic site with some special buildings, it is a site made up exclusively of special buildings and strongly connected to Neolithic (symbolic and most likely religious) beliefs.

View of Göbekli Tepe’s so-called main excavation area, Enclosure D in the front. (Copyright German Archaeological Institute, Nico Becker)

This symbolic world and Göbekli Tepe at its center clearly challenge conventional views on the organization, creative possibilities and potential of hunter-gatherers. This leads to the question how highly mobile hunter-gatherer groups were able to create a monumental site like Göbekli Tepe, and what repercussions this large-scale project may have had on their society.

Indicators for social differentiation

At Göbekli Tepe the enclosures of Layer III consist of several large megalithic elements cut from the surrounding limestone plateaus. The setting of the Neolithic quarries is demonstrated by numerous traces, between them an unfinished T pillar with a size of about 7 m and volume of 20 m³. The central pillars of Enclosure D weigh 10 metric tons each, and the pillars in the circle are only slightly smaller. Cutting, decorating, and transporting them is not a small task. There would of course also be the possibility that the enclosures were erected and constructed in the course of a longer period, but research into their building history does not seem to indicate this. On the other hand there is ample evidence for revisited work in already existing enclosures, for ongoing rearrangement, repair, depletion and re-use of some pillars in other enclosures. Consistent and intense work at thus seems very probable there.

Unfinished T-pillar in the quarries of Göbekli Tepe, tell in background. (Copyright German Archaeological Institute, Nico Becker)

There is some evidence for more than one group of people involved in construction activity. The image range of the different enclosures is far from random. In Enclosure A snakes are the dominating species, in Enclosure B foxes are frequent, in Enclosure C many boars are represented, while Enclosure D is more varied, with birds playing an important role. A possible connection of these animals to totems of different clans working at Göbekli Tepe is a possible line of interpretation which should be explored in future research.

To sum up, there is reason to believe that larger groups of people were active at Göbekli Tepe. Planning, organization and coordination of construction work were obviously necessary, as well as a mode to gather the needed workforce which most probably outnumbers the members of a single band or even a local group of hunter-gatherers. Some clues to the reasons people gathered at Göbekli Tepe come from the filing material of the enclosures. The fill material consists of limestone rubble, bones, fragments of stone artifacts and flint debitage (tools are rarer); its quite homogenous character makes the whole process of backfilling almost resembling a burial. Enclosure D alone comprised nearly 500 cubic meters of debris. With traces of permanent settlement absent, this readily leads to the idea of large, ritualized ‘work feasts’ rooted in the belief systems of the people congregating there. Large amounts of wild game were hunted and consumed. Feasting, respectively the organization of large feasts, is known ethnographically as a method to accumulate influence, to create hierarchies, and ultimately to exercise power over others. Yet there are even further indicators for social inequality in the early Neolithic archaeological record.

Limestone head from Göbekli Tepe, supposedly part of a sculpture similar to ‘Urfa Man’ (Photo: N. Becker, DAI).

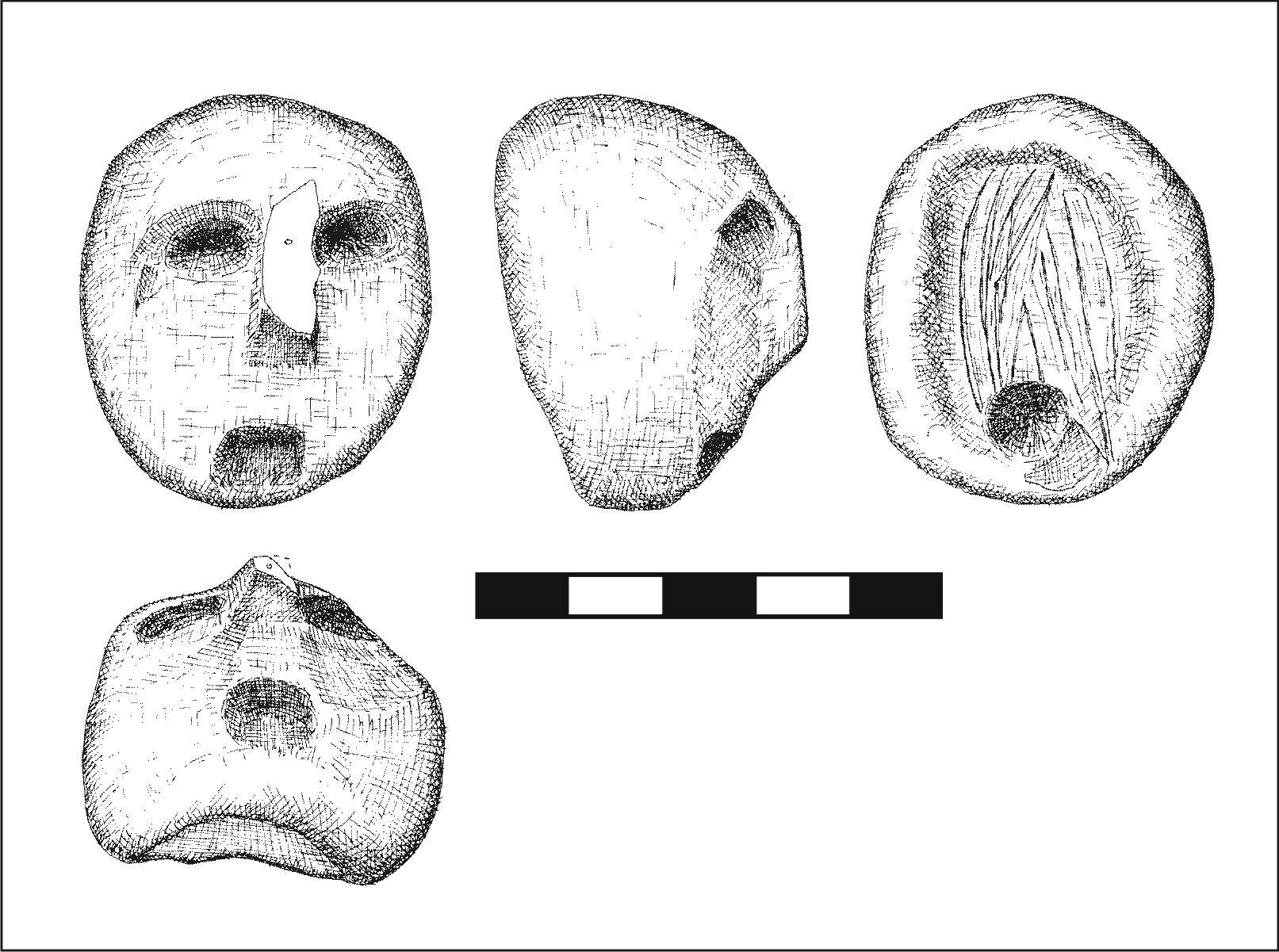

A general impression of the existence of hierarchical concepts within the groups constructing the Göbekli Tepe enclosures is conferred by the layout of these structures already. The smaller pillars in the circle walls are looking towards the larger central pair of pillars. Whatever gathering is depicted here, it does not seem to be one of equals. Another differentiation seems to exist between the clearly anthropomorphic, but abstract pillars and more natural human depictions in the style of the PPN sculpture of a man from Urfa-Yeni Mahalle. The ‘Urfa statue’, regarded as the oldest naturalistic life-sized sculpture of a human, has a face, and its eyes are depicted by deep holes with inset blade segments of black obsidian, but it lacks a mouth. The statue seems to be naked with the exception of a V-shaped necklace or collar. It is not entirely clear, but it seems that its hands are holding a phallus. Legs are not depicted; below the body there is a conical tap, which allows the statue to be set into the ground. From Göbekli Tepe there are several life-sized human heads made of limestone, which probably have been part of similar sculptures originally. The heads seem to have been intentionally broken off the statues and were in many cases deposited next to the T-shaped pillars in the course of refilling the enclosures. While their exact relation to the pillars remains unclear, it seems quite possible to assume that they represent another hierarchical level or another sphere compared to these abstracted pillar-beings. This would be a strong lead to assume a concept of hierarchy in the spiritual realm. The question at hand is, if real life was structured accordingly.

One symptom, and maybe a prerequisite for the evolution of social hierarchy is specialization and division of labor. Göbekli Tepe stands witness to the existence of both. It is hard to imagine that the reliefs on these pillars and the elaborated sculptures were made by inexperienced people. The uniformity of types, the coherent style, the exactness of realization all speak in favor of a fixed canon of motifs and techniques that had to be learned. While transport and erection of the monoliths may have been accomplished in a short time span by a large work force, the artistry seems to hint at highly specialized craft(s). It seems possible that a part of the population had to be set free from subsistence activities and were cared for at least for some time of the year by the others while learning and executing work at Göbekli Tepe. Of course, the intensity and duration of such work periods is hard to apprehend, and their effect may not have been decisive in restructuring a complete society in the short term.

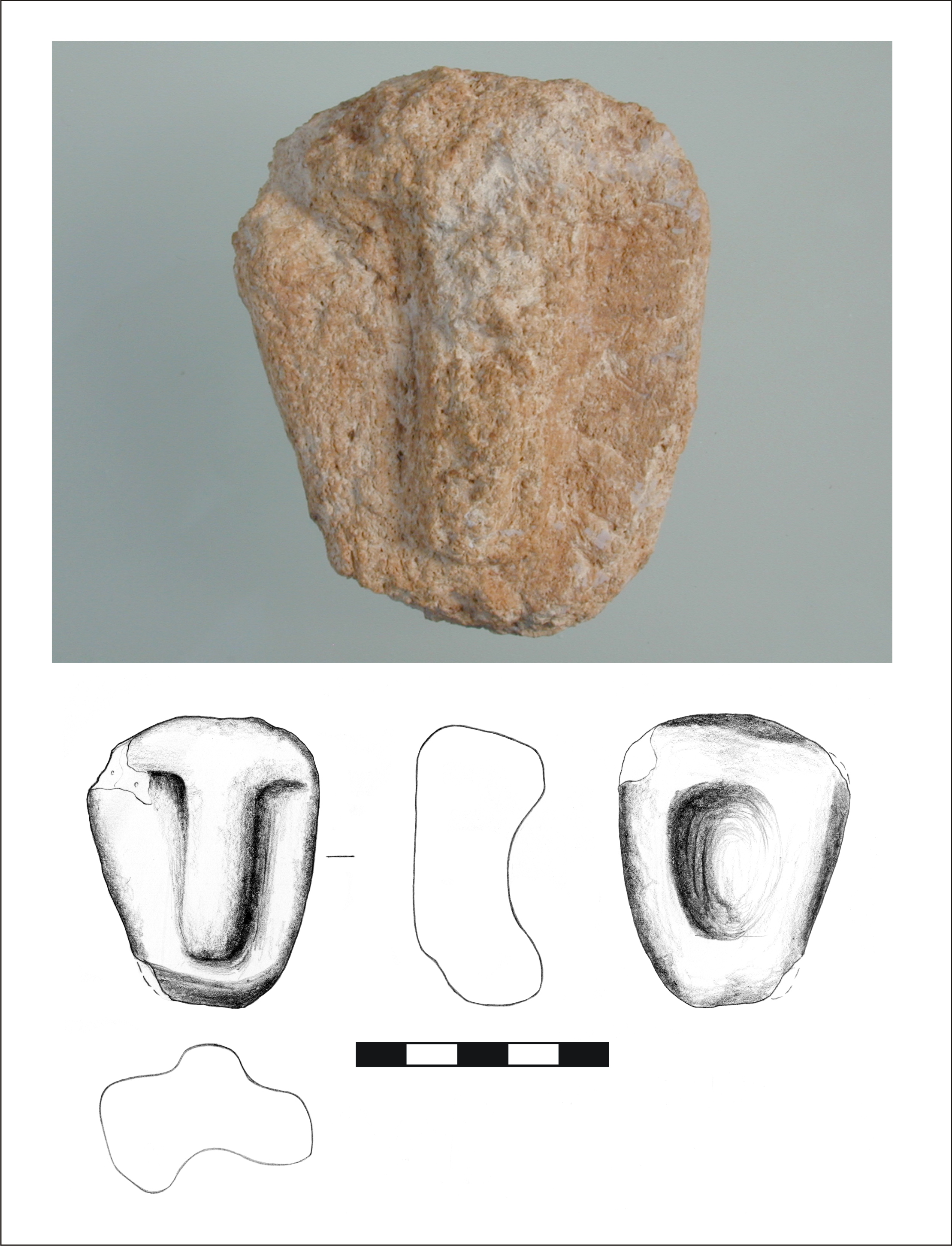

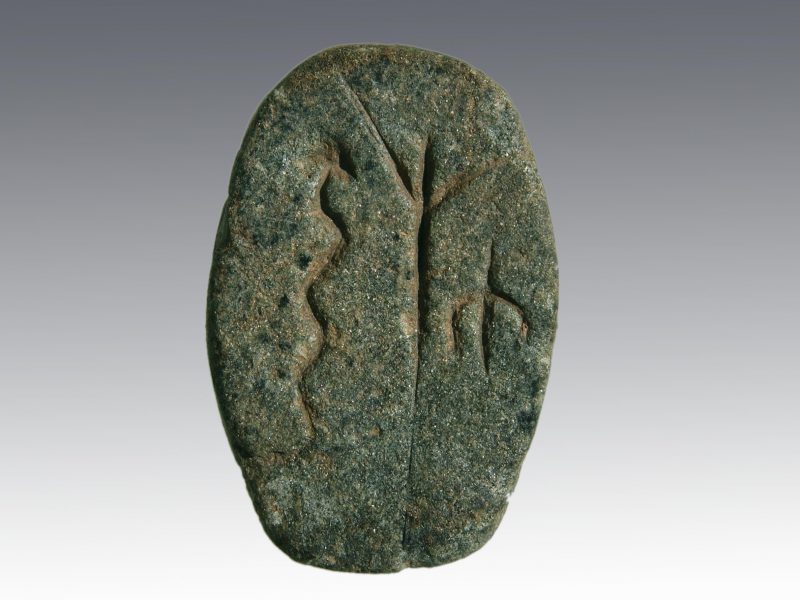

When trying to infer social hierarchization, archaeologists frequently turn to special treatment of individuals in funerary ritual or to ‚prestige’ items of material culture. At Göbekli Tepe, burials are missing so far, but it is not hard to find ‘special’ items. Looking at the portable material culture, there are spacer beads and buttons, often made of greenstone, zoomorphic pestles or ‚scepters’ of the so-called Nemrik type, elaborately decorated thin walled stone bowls, and, of course, decorated shaft straighteners and small stone tablets. The decorated tablets and shaft straighteners also pose an argument for specialization. In can be assumed that the signs on them were readable, because they repeat images and, more importantly, combinations of images known as well from the pillars, as from objects discovered at other sites in vicinity. They most likely represent a way to fix memories and knowledge of the society creating them in a form intelligible at least to initiated specialists. The challenge addressing these items as individual signs of social distinction at Göbekli Tepe lies in the fact that they come from the enclosures’ filling. They are not found in the contexts of their primary use, and there thus is no possibility to determine whether e.g. the stone bowls, the ‚scepters’ (if this determination is right), or the tablets were the individual property of persons, or part of the paraphernalia of cultic ceremonies. There are some leads though. The buttons and spacer beads, often made from greenstone and most likely part of the personal adornment, do appear frequently in Göbekli Tepe and in settlements with ‚special buildings’ like Nevalı Çori or Çayönü. They seem to be bound to such peculiar contexts and maybe to a group of religious specialists present there.

A look at other sites may strengthen this image a little more. The richly furnished burials found at Körtik Tepe [external link], a site partly contemporary with Göbekli Tepe’s Layer III (but apparently starting much earlier) and sharing much of its material culture, situated more to the East in the Tigris region, are very important for understanding early Neolithic social hierarchy. Besides the settlement, at Körtik Tepe more than 450 graves have been discovered. The amount of grave goods differs considerably, there is also a large number of graves without any. Some skeletons show evidence for complex rites prior and posterior to burial, including the decoration of bones with ochre and lime-plaster. Of course, a simple relationship between burial gifts, elaborate grave rites and the social status of the deceased cannot be drawn, as the furnishing of graves also (and sometimes predominantly) is determined by the belief system and values of society or the views of the bereaved on the deceased. The broken objects at Körtik Tepe, in many cases stone bowls, could very well hint at a ritual deposition of equipment used in celebrations at the graves more than at the personal belongings of the dead. Such celebrations may implicitly and in the first place have served the purpose of handling the loss produced by the death for the social group. However, not all individuals seem to have received equal attention, and the excavators also observed that grave goods generally got more elaborated and numerous over time, which they take as a sign of increasing social hierarchization. The graves of Körtik Tepe thus seem to offer tentative evidence for social distinction among groups contemporary with Göbekli Tepe.

-

-

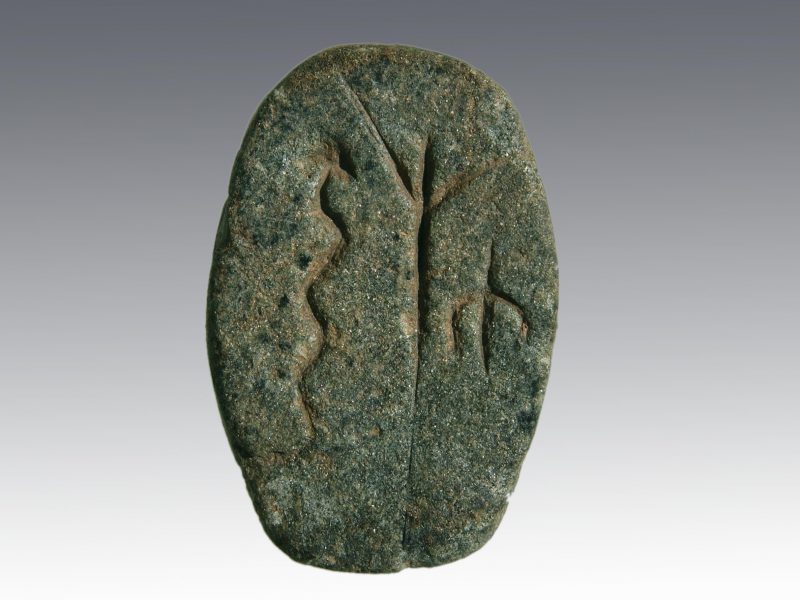

Plaquette with depiction of a snake, a human (?) and a bird (Photo: Irmgard Wagner, Copyright DAI).

-

-

Fragment of a decorated stone bowl from Göbekli Tepe (Photo. Schmidt, Copyright DAI).

-

-

Fragment of a decorated stone bowl from Göbekli Tepe (Photo N. Becker, Copyright DAI).

Most interestingly, also decorated stone plaquettes are part of burials at Körtik Tepe, marking them as possible individual property or signs of the social function of some of the deceased. The exact number of decorated plaquettes from Körtik is not clear, but it seems to be a restricted find group. It is possible that the possession of plaquettes themselves and – probably more important – the knowledge stored on them in abstract and symbolic form was restricted to a certain group of people. This would again hint at specialists in memory, ritual and maybe religion, drawing their importance to the group from memorizing, saving and reproducing crucial knowledge.

Restriction of the access to knowledge and participation in rituals seems to be attestable also at Göbekli Tepe. On a general level, some object classes known from settlements are missing. For example, awls and points of bone are nearly completely absent. The tasks carried out with them probably were not practiced here, and it may well be that the part of the population carrying them out was absent, too. Further, clay figurines are absent completely from Göbekli Tepe. This observation gains importance in comparison to Nevalı Çori, where clay figurines are abundant, missing only in the ‘cult building’ with its stone sculptures and T-shaped pillars. Clay and stone sculptures may thus well form two different functional groups, one connected to domestic space (and domestic cult?) and one to the specialized ‘cult buildings’ – and to another sphere of ritual also evident at Göbekli Tepe. Its iconography is exclusively male, and while evidence for some domestic tasks is missing, there is evidence for flint knapping on a much larger scale than in any contemporary settlement, and shaft straighteners are very frequent, too. Göbekli Tepe could have been a place for just a part of society, for male hunters. At least their ideology seems to be exclusively represented at the site.

Another element of restriction is posed by the enclosures. They are not of a size to accommodate very large groups of people at a time. If we imagine them open to the sky, then a certain public aspect would have to be taken into account, but another possibility is a reconstruction along the lines of largely subterranean buildings accessible through openings in the roof, similar to the kivas of the North-American Southwest, rather unimpressive and hidden from the outside. It is a distinct possibility that only a small group of religious specialists had access to the enclosures.

As mentioned above, at Göbekli Tepe there is evidence for constant construction activity. In Addition to the erection of new monuments, activities took also place in already existing enclosures. New circle walls were added, and the re-use of pillars from other, dismantled enclosures is a frequent phenomenon. The general impression is that working at Göbekli Tepe in itself was of central importance to PPN people. One reason for this may lie in the strengthening of social cohesion such activities in combination with feasting (maybe preluded by communal hunts) bring about, but building and rebuilding Göbekli Tepe – and maybe other sites like it – may also have been a way to gain and maintain social power and influence by those possessing the knowledge necessary to construct and meaningfully decorate the ‘special buildings’.

Complementing the element of cohesion, there may also be signs of competition at Göbekli Tepe. The enclosures vary in size, in the density of iconography, and ultimately in the amount of labor invested. Also, as mentioned above, different species of animals dominate in different enclosures. That observation opens up the possibility of the circles being constructed by different groups. The possibility of competitive behavior among those groups, or individuals leading them, can thus not be ruled out.

Conclusion

The large-scale feasting at Göbekli Tepe seems partly to have had the character of work feasts to accomplish a common, supposedly religiously motivated task. The enclosures erected there convey the impression of gatherings through their layout, and, while signs for social stratification exist, this aspect – the gathering of people for a collective aim – should not be lost from sight completely in favor of competition and power acquisition by individuals. In any case it would seem that competition for influence, at least at Göbekli Tepe, was not open to everyone who was able to throw a large feast. Access to and command of knowledge crucial to society’s identity and well-being may have served as a social barrier hindering individuals to step outside of the given limits, while being the basis for power over the work-force of others for a restricted group of people. In conclusion, the notion of a ‘transegalitarian society’ with beginning social hierarchization on several levels brought forward by Brian Hayden seems to fit the image emerging from sites like Göbekli Tepe and Körtik Tepe.

It may be premature however to move beyond the simple observation of the early evolution of social hierarchy. We should take the limits of the momentarily available archaeological evidence into account. Göbekli Tepe is a very special site in the context of cult, the perpetuation of cultural knowledge and, maybe, ultimately religion. This is an important aspect of a society, but it is just one facet of many. Feasting in a cultic context away from settlements may have been a way to gain influence in the early Neolithic world, but at the moment it is hard to integrate into a complete picture. Complementary evidence from settlements is needed to understand how far social differentiation already influenced all aspects of life in the earlier PPN, how stable power aggregated by an individual might have been and how far his authority over others may have reached. At Göbekli Tepe, the collective aspect of accomplishing work through feasting generally seems to hint at a more indirect and maybe fragile form of power connected to a certain task.

Acknowledgement

We are grateful the General Directorate of Antiquities of Turkey for kind permission to excavate this important site. Research at Göbekli Tepe is funded by the German Archaeological Institute (DAI) and the German Research Foundation (DFG). This text is partly based upon the following work: O. Dietrich, J. Notroff, K. Schmidt. 2017. Feasting, social complexity and the emergence of the early Neolithic of Upper Mesopotamia: a view from Göbekli Tepe. In: R. J. Chacon, R. Mendoza (eds.), Feast, Famine or Fighting? Multiple Pathways to Social Complexity. New York: Springer, 91-132.

Recent Comments