Recently we got a couple of notes and comments regarding a number of finds supposedly attributed to the early Neolithic site of Göbekli Tepe. Finds we surprisingly never addressed or mentioned or published anyway. Of course this raised questions. Not only among our readers, but also in the research team. So, I picked three of these mysterious objects and tried to follow their path all the way back. A lesson in ‘alternative facts’, their easy creation – and quick multiplication on the world wide web.

The first of these items we’re having a look into is this detailed and rather ‘life-like’ sphinx-sculpture – linked to a caption saying “The oldest known sphinx was found in Göbekli Tepe …”.

Stylistically, this sculpture already looks quite different from any other prehistoric piece of art we know of, yet those coming from Pre-Pottery Neolithic Göbekli Tepe in particular. The carefully sculpted face and body are more reminiscent of ‘classic’ ancient Greek or Roman sculptures – or those of the 18th and 19th century ‘romanticising’ sculptures. Also, the material does not really look like the yellowish-worn limestone so characteristic for Göbekli Tepe’s sculptures.

The statement connected to this depiction is even more surprising – since actually there is no single sphinx known from Göbekli Tepe (or any other related PPN-site of the region) reported. In fact, composite – hybrid – creatures are generelly very rare in prehistoric art. With a few excepetions, the concept of chimaeras seems to have become a more common (or at least more often depicted) mythological trope at a later time in human history.

Finally, with a little bit of research the sculpture in question here can be identified as being part of the garden decoration of the Royal Palace of La Granja [external link] in the Spanish town of San Ildefonso – dating to the 18th century. AD.

The second object on this list is a bit trickier. Indeed it seems to be a rather large stele showing the relief of some upright standing person. Stone and setting somehow look similar to what we would expect from Göbekli Tepe – although the style of depiction and the building visible to the right suspiciously do not really look familiar from an Anatolian early Neolithic point of view.

Again, a closer look at the actual depiction makes it clear that we are dealing with something different here. The person shows characteristical features we would expect from an ape. In particular the head, face, and tail give it away: this is a depiction of Hanuman, a Hindu god in the shape of a monkey. With this information at hand it is only a question of further reading to identify the stele as one of the monuments at the Virupakasha Temple in Hampi [external link], a World Heritage Site in southern India – dating back as much as the 7th century AD, but definitely not the Neolithic period.

Again, a closer look at the actual depiction makes it clear that we are dealing with something different here. The person shows characteristical features we would expect from an ape. In particular the head, face, and tail give it away: this is a depiction of Hanuman, a Hindu god in the shape of a monkey. With this information at hand it is only a question of further reading to identify the stele as one of the monuments at the Virupakasha Temple in Hampi [external link], a World Heritage Site in southern India – dating back as much as the 7th century AD, but definitely not the Neolithic period.

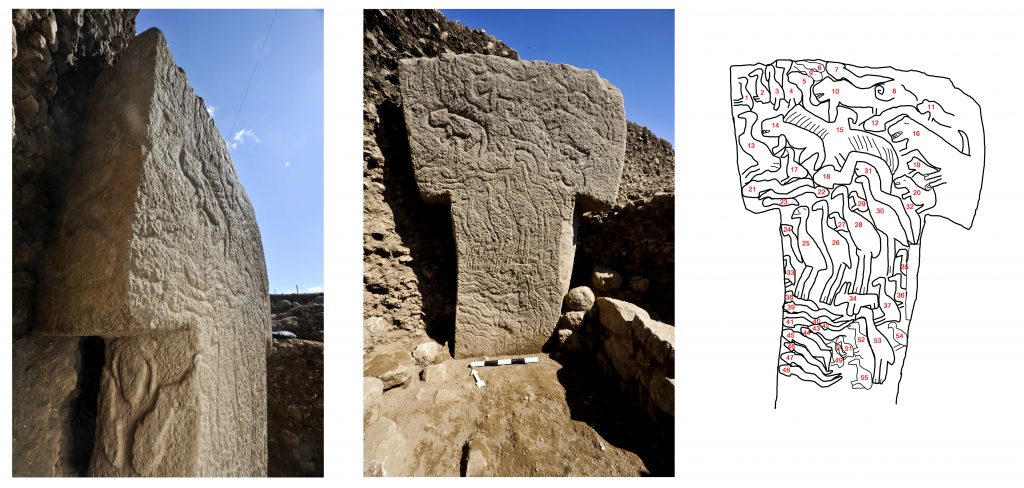

Finally, the last find examined here is this standard-like object of which the caption claims it is a “G[ö]bekli Tepe god of the constellation of Orion.” Besides the challenges to project modern (or at least historical) star constellations into prehistory and even more prehsitoric art (as we already discussed here) and the terminological issues surrounding lables like ‘god’, ‘gods’, and even ‘temple’ (discussed here earlier), this piece, again, does look like nothing we know from the site of Göbekli Tepe or any other Neolithic find spot in the region.

In fact, a stylistic comparison eventually offers a lead to modern Iran. A couple of elaborate objects dating to the Bronze Age period (i.e. the 3rd millennium BC) from this region show quite some parallels. They are linked to the so-called Jiroft culture which, unfortunately, still remains raher obscure since the majority of finds associated with Jiroft are coming from illegal excavations and we do not know much about them. But again, they’re neither related to the Anatolian Neolithic nor the site of Göbekli Tepe.

These three examples should be sufficient and representative for the point we would like to make with this blog post: it’s easy to come up with an idea, it’s easy to form hypotheses. Honestly, we as scientists do it too, all the time. But every hypothesis needs to be checked, material needs to be compared, sources reviewed. We’re living in times where facts can be made up as ‘alternatives’. Stay curious, but stay suspicious. Check the facts, check the sources. And when in doubt … ask an archaeologist (or any other expert).

Recent Comments