This text has been published originally (and in slightly different form) as a short contribution by Oliver Dietrich and Klaus Schmidt (†) in Neo-Lithics [external link] 1/17, 43-46.

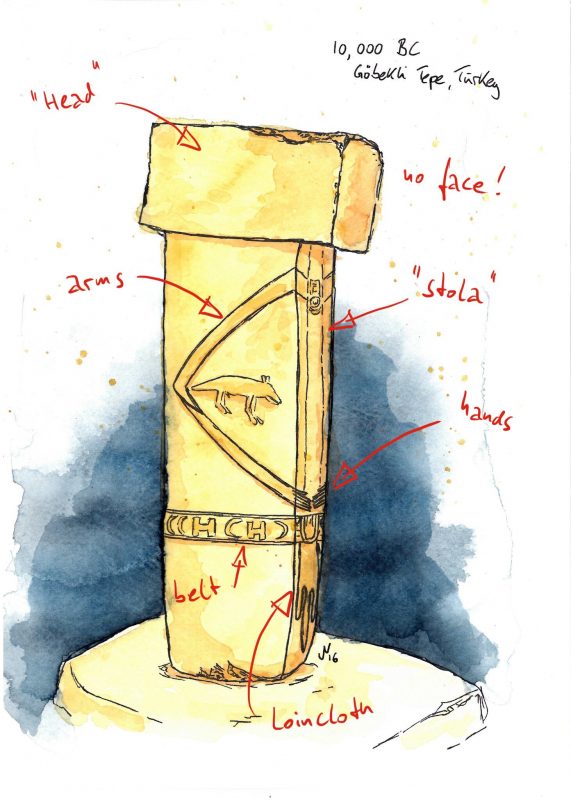

The most striking aspects of Göbekli Tepe are without question the monumentality of the site and the rich imagery. Besides the reliefs on the pillars, there is a wide range of stone sculptures and figurines. Klaus Schmidt, who excavated the site for 20 years, has dedicated several papers to this find group (Hauptmann and Schmidt 2007; Schmidt 1998; 1999; 2008; 2009; 2010); a comprehensive synthesis is still missing (for the anthropomorphic sculpture Dietrich et al. forthcoming). A total of 149 sculptures has been found to date at Göbekli Tepe. Of these, 86 depict animals, 38 humans, four anthropomorphic masks, three phalli, nine are human-animal composite sculptures and a further nine are indeterminable. Many of the sculptures are in a fragmentary state, which may have its reason in social practises connected to the early Neolithic imagery – including intentional fragmentation and deposition of a selection of fragments, mostly heads in meaningful contexts next to the pillars (Becker et al. 2012; Dietrich et al. forthcoming). Many of the fragments may have been originally part of sculptures in the shape of the ‘Urfa Man’, the oldest life-sized human sculpture currently known, discovered during construction work at Urfa-Yeni Mahalle (Hauptmann 2003; Schmidt 2010. 247, 248-249). But there is also a range of other types, and the current contribution is dedicated to one of those.

The figurine

During the 2012 autumn excavation season at Göbekli Tepe, a small figurine (5,1×2,3×2,7 cm) was handed in as a surface find from the north-western hilltop of the tell (Fig. 2). The motif of the figurine is an ithyphallic person sitting with legs dragged toward his body on an unidentifiable object. He is looking up and grasping his legs. Between the legs, a large erect phallus is depicted (Fig. 3), and a quadruped animal is sitting on the person´s left shoulder (Fig. 4). As one half of the figurine has a thick layer of sinter, the question whether there originally was another animal on the other shoulder remains open. The animal species cannot be determined with security neither, but the general form is consistent with depictions of large wildcats or bears at Göbekli Tepe (e.g. Schmidt 1999. 9-10, nr. A8). The material of the sculpture is unusual for the site on the other hand. Nearly all sculptures and figurines so far known from Göbekli Tepe were made from local limestone. The new figurine is most likely made from nephrite[1]. The figurine is perforated crosswise in its lower part. A functional interpretation for this detail is hard to give as one perforation would have sufficed to wear it as a pendant for example. Maybe the figurine was meant to be fixed to a support.

-

-

The seated figurine from Göbekli Tepe (copyright DAI, Photo N. Becker).

-

-

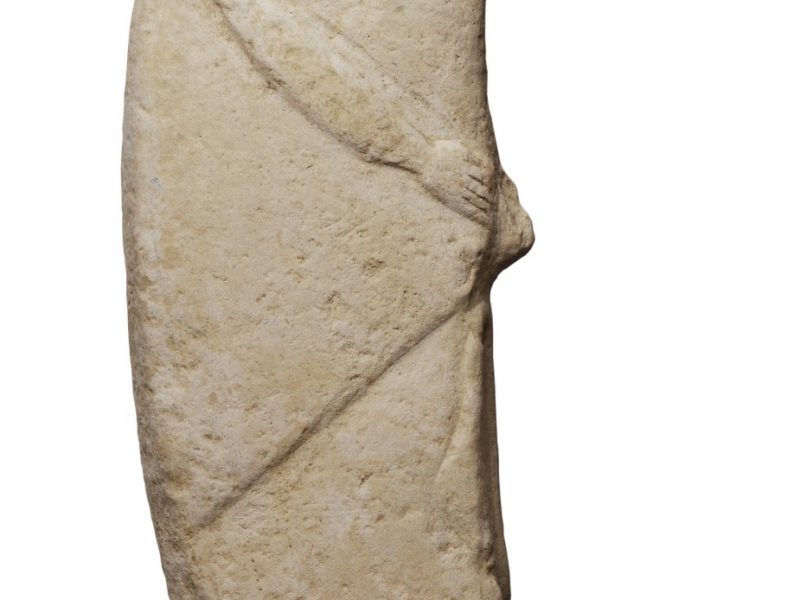

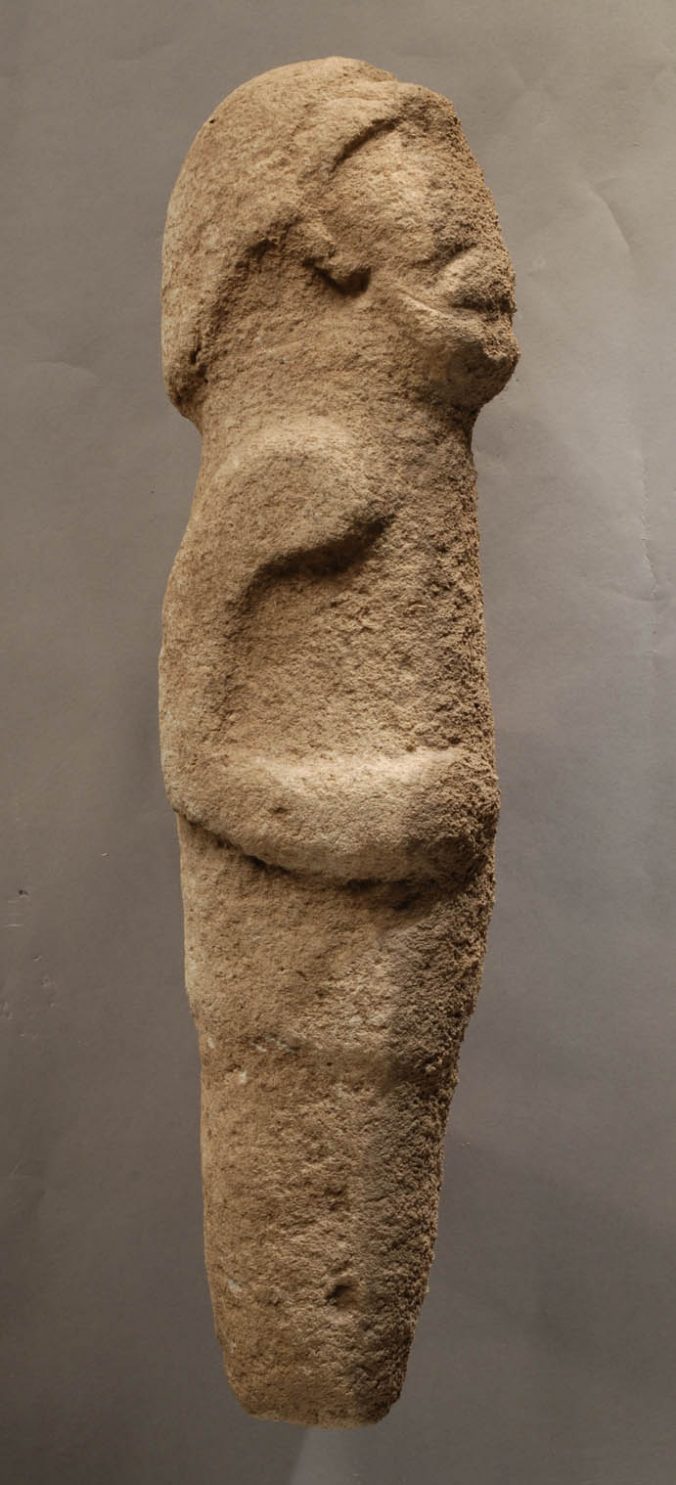

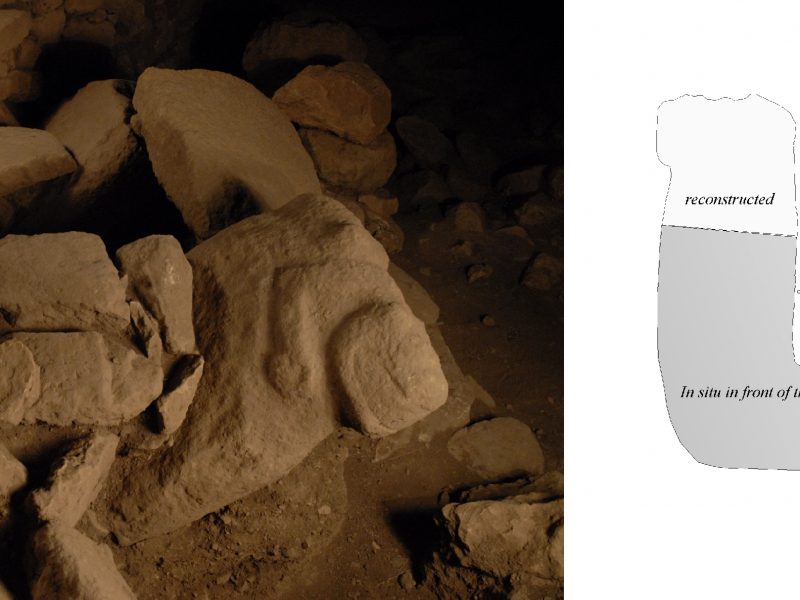

The unclear find circumstances and the unusual material raise the question of the figurine´s provenance. The sinter layer is a characteristic for finds from Göbekli Tepe (and clearly indicates that the figurine was originally buried with the right side down), but could have formed of course also at another site with similar natural conditions. There is however an older find that could represent a fragment of the same figurine type. This fragment, comprising head and shoulder of a small figurine (3,9×4.0x2.8cm) made from brownish limestone, was discovered in 2002, also on the surface of the tell (Fig. 5). There are two more examples of larger seated sculptures from Göbekli Tepe. A first depiction of a seated person (h. 32.5cm; Fig. 6), badly preserved, was found on the surface of the tell, too (Schmidt 1999. 9, Plate. 1/1). Here, the hands are brought together under the belly, the gesture reminds of the ‘Urfa Man’ who most likely is presenting a phallus (Hauptmann 2003), but unfortunately the lower part of the sculpture is not preserved. A snake could be depicted crawling up the back and head of the sculpture, but this remains uncertain, too. Another example (h. 44cm) was found more recently in a deep sounding in the northwestern depression of the tell (Area K10-55, Locus 21.2; Fig. 7). The find context is still under evaluation, much speaks for a PPN B date so far. The preservation of this sculpture is also rather bad, the lower part is missing again. Both examples show some clear differences compared to the figurine: the arms are folded in front of the body, there is no animal on the shoulder, and the persons seem to sit on the ground, not on some object. As the lower part is missing we cannot be sure whether a phallus was depicted. Summing up, it seems nevertheless reasonably sure that the new figurine is from Göbekli Tepe – and represents a type, or variant, not known so far in the site´s sculptural inventory.

Date and analogies

Without knowledge of the original find context, or analogies from clear contexts, there is no possibility to attribute the new figurine to one of Göbekli Tepe´s architectural horizons – Layer III with the PPN A and possibly early PPN B large stone circles formed of T-shaped pillars, or Layer II with early/middle PPNB rectangular or sub-rectangular buildings. Offsite analogies also seem to be scarce.

29 similarly seated limestone figurines are known from Mezraa-Teleilat´s phase IIIB, i.e. the Late PPN B / early Pottery Neolithic transition (Özdoğan 2003. 515-516, Figures 1a-c, 2b-c, 4, 5; Özdoğan 2011. 209, Figures 14-21; Hansen 2014: 271, Figure 9). One more find can be added to this group, a more recently published stone figurine from Çatalhöyük (Hodder 2012. Figure 14b; Hansen 2014. 271). Although the overall form is very similar, the figurines from Mezraa-Teleilat and Çatalhöyük are much more abstracted, the former are sitting on armchair-like seats, wear robe-like clothes and in some cases belts, and examples with animals on the shoulders seem to be missing. As the latest finds from Göbekli Tepe date to the middle PPN B, the figurine must be older than the finds from Mezraa Teleilat and Çatalhöyük. Whether the naturalistic sculpture(s) from Göbekli Tepe can be regarded as the prototypes for this group and thus also a similar meaning could be proposed, cannot be answered with security for now.

-

-

Seated limestone sculpture from Göbekli Tepe (© DAI, Photo N. Becker).

-

-

Seated limestone sculpture from Göbekli Tepe (© DAI, Photo T. Goldschmidt).

Further analogies are hard to find. The much later standing female clay figurines holding leopard cubs from Hacılar (e.g. Mellaart 1970. Figure 196-197), and the so-called ‘Mistress of Animals’, a female figurine seated on a leopard and holding a leopard cub (Mellaart 1970. Figure 228), or, in another case, seated on two leopards and holding their tails (Mellaart 1970. Figure 229) are different in gesture and topic.

Discussion

The meaning of the figurine from Göbekli Tepe remains enigmatic. The finds from Mezraa Teleilat and Çatalhöyük seem to be the best analogies for now. But in contrast to this group, the find discussed here has the animal on the shoulder (or one on each shoulder originally?) as an important characteristic. There are several examples of animal-human composite sculptures from Göbekli Tepe. But they show animals – birds and quadrupeds – on the heads of people, grabbing them with their claws, maybe carrying the heads away (e.g. Beile-Bohn et al. 1998.66-68, Figure 30-31; Becker et al. 2012.35). This kind of iconography most likely relates to Neolithic death cult or beliefs (Schmidt 1999.7-8). The new sculpture, with one or two animals in the shoulder area, does not fit well into this group. The animal is clinging to the shoulder in a crouched position, there is no indication of aggression or attack (Fig. 4), or a reaction of the sitting person. The animal could thus have a completely different meaning. We could be dealing with a more metaphorical relationship between man and animal here.

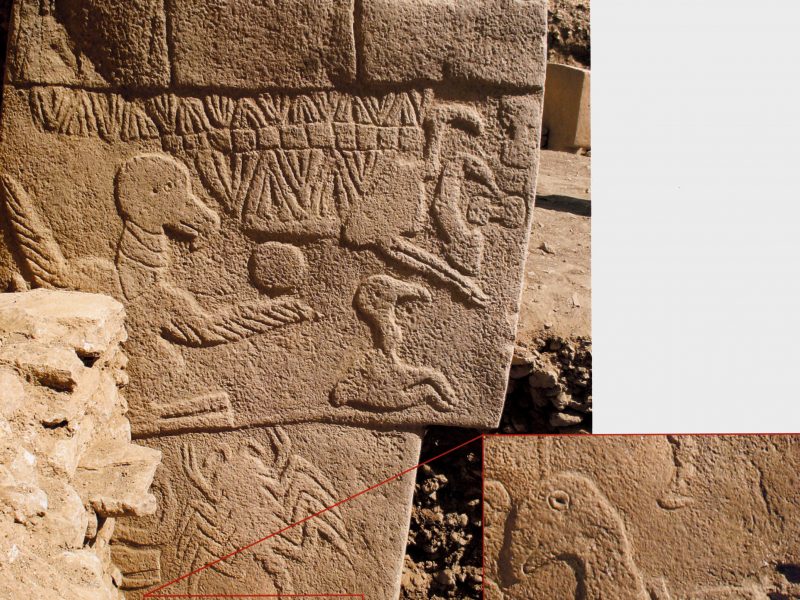

Fragment of a limestone figurine discovered in 2002 at Göbekli Tepe (© DAI, Photo I. Wagner).

At Göbekli Tepe, animal symbolism seems to have an emblematic/totemic connotation in some cases. In every one of the monumental enclosures of Layer III, one animal species is dominant by quantity of depictions (Notroff et al. 2014.97-98, Fig. 5.9). In Enclosure C for example boars have this role, in Enclosure A snakes, Enclosure B has many undecorated pillars, but foxes are more frequent, while Enclosure D is more diverse, with birds and insects playing an important role. Given this background, one hypothesis would be that the animal characterises the person depicted in the figurine as a member of a certain group.

The other important characteristic of the depiction is the prominent erect phallus. Göbekli Tepe´s iconography is generally nearly exclusively male (e.g. Dietrich and Notroff 2015.85), and the phallus features prominently in several depictions of animals and humans. For example, a headless ithyphallic body is depicted on Pillar 43 amongst birds, snakes and a large scorpion (Schmidt 2006). Although the central pillars of the large enclosures are clearly marked as human through the depiction of arms, hands, and in the case of Enclosure D also items of clothing, their sex is not indicated. An erect phallus however is a prominent feature of the foxes depicted on several of the central pillars. There are also a few phallus sculptures from the site (e.g. Schmidt 1999.9, Plate 2/3-4).

It is hard to say whether all these diverse depictions / contexts share a similar basic meaning, or a multitude of meanings is implied. There is a vast ethnographic and historic repertoire of phallic depictions in the context of power, dominance, aggression, marking of boundaries/ownership, and apotropaism (e.g. Sütterlin-Eibl-Eibesfeldt 2013 with bibliography). Phallic symbolism is also often integrated in rites of admission in social groups. The association of animal and phallic symbolism in the sitting (watching?) figurine could hypothetically hint at such rites of admission, it could be a mnemonic object illustrating an aspect/moment of the rituals involved. However, further finds from secure and informative contexts from Göbekli Tepe, or elsewhere, should be awaited to shed some more light on this new figurine type.

Bibliography

Becker N., Dietrich O., Götzelt Th., Köksal-Schmidt Ç., Notroff J., Schmidt, K. 2012. Materialien zur Deutung der zentralen Pfeilerpaare des Göbekli Tepe und weiterer Orte des obermesopotamischen Frühneolithikums. Zeitschrift für Orient-Archäologie 5: 14-43.

Beile-Bohn M., Gerber, C., Morsch, M. Schmidt K. 1998. Neolithische Forschungen in Ober-mesopotamien. Gürcütepe und Göbekli Tepe. Istanbuler Mitteilungen 48: 5-78.

Dietrich O., Notroff, J. 2015. A sanctuary, or so fair a house? In defense of an archaeology of cult at Pre-Pottery Neolithic Göbekli Tepe. In N. Laneri (ed.), Defining the Sacred: Approaches to the Archaeology of Religion in the Near East. Oxbow. Oxford: 75-89.

Dietrich, O., Heun, M., Notroff, J., Schmidt, K., Zarnkow, M. 2012. The Role of Cult and Feasting in the Emergence of Neolithic Communities. New Evidence from Göbekli Tepe, South-eastern Turkey. Antiquity 86: 674-695.

Dietrich, O., Köksal-Schmidt, Ç., Notroff, J., Schmidt, K. 2013. Establishing a Radiocarbon Sequence for Göbekli Tepe. State of Research and New Data. Neo-Lithics 1/13: 36-41.

Dietrich, O., Notroff, J., Schmidt, K. 2017. Feasting, social complexity and the emergence of the early Neolithic of Upper Mesopotamia: a view from Göbekli Tepe. In R. J. Chacon, R. Mendoza (eds.). Feast, Famine or Fighting? Multiple Pathways to Social Complexity. Springer. New York: 91-132.

Dietrich, O., Dietrich, L., Notroff, J. Forthcoming. Anthropomorphic imagery at Göbekli Tepe. In J. Becker, C. Beuger, B. Müller-Neuhof (eds.), Iconography and Symbolic Meaning of the Human in Near Eastern Prehistory. Workshop Proceedings 10th ICAANE in Vienna, Harrassowitz Verlag. Wiesbaden.

Hansen, S. 2014. Neolithic figurines in Anatolia. In M. Özdoğan, N. Başgelen, P. Kuniholm (eds.), The Neolithic in Turkey 6. 10500-5200 BC: Environment, Settlement, Flora, Fauna, Dating, Symbols of Belief, with Views from North, South, East and West. Archaeology and Art Publications. Istanbul: 265-292.

Hauptmann, H. 2003. Eine frühneolithische Kultfigur aus Urfa. In M. Özdoğan, H. Hauptmann, N. Başgelen (eds.), From villages to towns. Studies presented to Ufuk Esin. Archaeology and Art Publications: Istanbul: 623-636.

Hauptmann, H., Schmidt K. 2007. Die Skulpturen des Frühneolithikums. In Badisches Landesmuseum (ed.), Vor 12.000 Jahren in Anatolien. Die ältesten Monumente der Menschheit. Theiss Verlag. Stuttgart: 67-82.

Hodder, I. 2012. Renewed work at Çatalhöyük. In M. Özdoğan, N. Başgelen, P. Kuniholm (eds.), The Neolithic in Turkey 3. Central Turkey. Archaeology and Art Publications. Istanbul: 245-277.

Mellaart, J. 1970. Excavations at Hacılar (2). University Press. Edinburgh.

Notroff, N., Dietrich, O., Schmidt, K. 2014. Building Monuments – Creating Communities. Early monumental architecture at Pre-Pottery Neolithic Göbekli Tepe. In J. Osborne (ed.), Approaching Monumentality in the Archaeological Record. SUNY Press. Albany: 83-105.

Özdoğan, M. 2003.A group of Neolithic stone figurines from Mezraa-Teleilat. In M. Özdoğan, H. Hauptmann and N. Başgelen (eds.), From villages to towns. Studies presented to Ufuk Esin. Archaeology and Art Publications. Istanbul: 511-523.

Özdoğan, M. 2011. Mezraa-Teleilat. In: M. Özdoğan, N. Başgelen, P. Kuniholm (eds.), The Neolithic in Turkey 2. The Euphrates Basin. Archaeology and Art Publications. Istanbul: 203-260.

Schmidt, K. 1999. Frühe Tier- und Menschenbilder vom Göbekli Tepe. Istanbuler Mitteilungen 49: 5-21.

Schmidt, K. 1998. Beyond daily bread: Evidence of Early Neolithic ritual from Göbekli Tepe, Neo-Lithics 2/98: 1-5.

Schmidt, K. 2006. Animals and a Headless Man at Göbekli Tepe. Neo-Lithics 2/2006: 38-40.

Schmidt, K. 2008. Die zähnefletschenden Raubtiere des Göbekli Tepe. In: D. Bonatz, R. M. Czichon, F. Janoscha Kreppner (eds.), Fundstellen. Gesammelte Schriften zur Archäologie und Geschichte Altvorderasiens ad honorem Hartmut Kühne. Harrassowitz Verlag. Wiesbaden: 61-69.

Schmidt, K. 2009. Göbekli Tepe – eine apokalyptische Bilderwelt aus der Steinzeit. Antike Welt 4: 45-52.

Schmidt, K. 2010. Göbekli Tepe – The Stone Age Sanctuaries. New results of ongoing excavations with a special focus on sculptures and high reliefs, Documenta Praehistorica XXXVII: 239-256.

Schmidt K. 2012a. A Stone Age Sanctuary in South-Eastern Anatolia. exOriente: Berlin.

Sütterlin, C., Eibl-Eibesfeldt, I. 2013. Human cultural defense: means and monuments of ensuring collective territory. Neo-Lithics 2/13: 42-48.

[1] Optical classification by Klaus Schmidt.

Recent Comments