We already expressed a couple of thoughts and remarks on a paper published in Mediterranean Archaeology and Archaeometry in which Martin B. Sweatman and Dimitrios Tsikritsis have suggested (original article accessible here: [external link]) that the early Neolithic monumental enclosures at Göbekli Tepe were space observatories and the site’s complex iconography the commemoration of a catastrophic astronomical event (‘Younger Dryas Comet Impact’).

Meanwhile we were putting together a more elaborate reply with further arguments and references which, in our opinion, challenge the interpretation and add more context to the paper’s discussion of Göbekli Tepe’s iconography in the light of the early Neolithic in Upper Mesopotamia. The editors of Mediterranean Archaeology and Archaeometry kindly agreed to publish our response in the same journal as the original article by Sweatman and Tsikritsis.

The paper (J. Notroff, O. Dietrich, L. Clare, L. Dietrich, J. Schlindwein, M. Kinzel, C. Lelek-Tvetmarken, D. Sönmez: More than a vulture: A response to Sweatman and Tsikritsis. Mediterranean Archaeology and Archaeometry 17(2), 2017, 57-63.) can be accessed online: [external link].

The mound of Göbekli Tepe seen from the south. (Photo: K. Schmidt, DAI)

Our reservations, which are not meant to silence any further archaeoastronomic discussion for Göbekli Tepe at all but rather comment on a number of discrepances we see in the interpretation, are summed up here:

1. The original layout of Göbekli Tepe’s monumental round-oval buildings is still subject of ongoing research (none of these structures are completely excavated as of yet). One should be aware that many of the T-pillars incorporated into the enclosures at Göbekli Tepe are not standing in their original positions and the buildings underwent significant modification during their life-cycles. Building archaeology studies have revealed that in many cases pillars were ‘recycled’, i.e. pulled out and used elsewhere. The monuments as we see them today are the culmination of multi-phase building and rebuilding events. Additionally, there is the significant possibility that we are dealing with roofed structures; this fact alone would pose limitations to a function as sky observatories.

2. The chronological frame Sweatman and Tsikritsis suggest for Pillar 43 (10950 BC +/- 250 years) is still 700-1000 years older than the oldest radiocarbon date so far available for Enclosure D (which stems from organic material retrieved from a wall plaster matrix). While there is evidence for later re-use of pillars (see above), assuming such a long tradition of knowledge relating to an unconfirmed (ancient) cosmic event appears extremely far-fetched. So far, any available date for Göbekli Tepe rather marks the end than the beginning of the Younger Dryas.

3. The assumption that asterisms are stable across time and cultures is not convincing. It is highly unlikely that early Neolithic hunters in Upper Mesopotamia recognized the exact same celestial constellations as described by ancient Egyptian, Arabian, and Greek scholars, which still populate our imagination today.

4. Sweatman and Tsikritsis’ contribution appears incredibly arbitrary, considering images adorning just a few selected pillars. Meanwhile more than 60 monumental limestone T-pillars are known from Göbekli Tepe – among these many feature similar carved low reliefs of animals and abstract symbols, a few even as complex as Pillar 43 (e.g. Pillar 56 in Enclosure H). Furthermore, the iconographic programme is not restricted to the limestone pillars; it is known from other find groups (including stone vessels, shaft straighteners, and plaquettes) not only from Göbekli Tepe but also from numerous contemporary sites in the wider region.

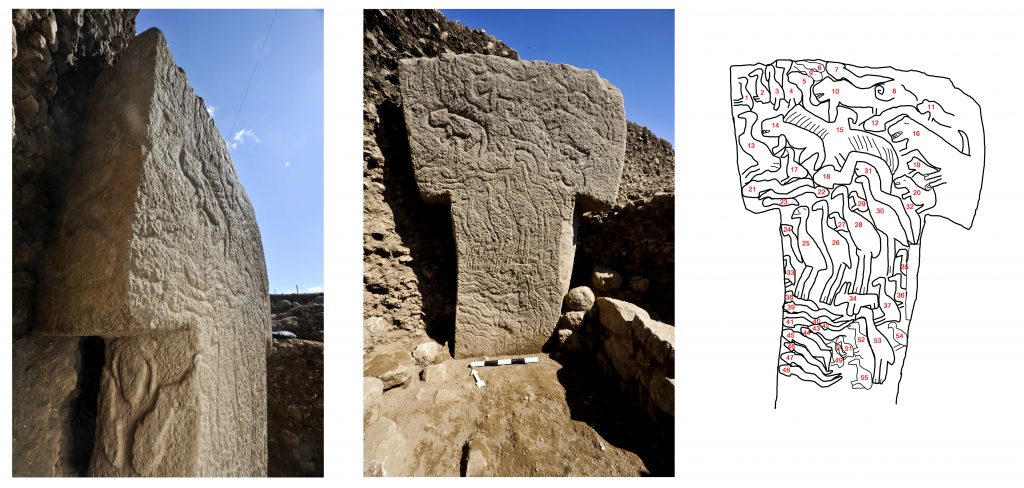

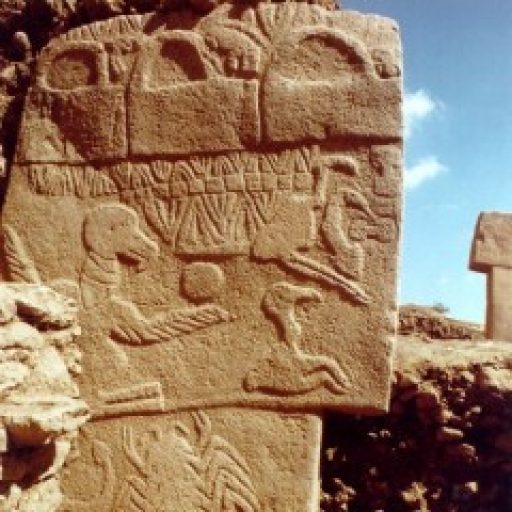

Pillar 56 from Enclosure H is another example for the rich and often complex iconography of Göbekli Tepe. (Photos & drawing: N. Becker, DAI)

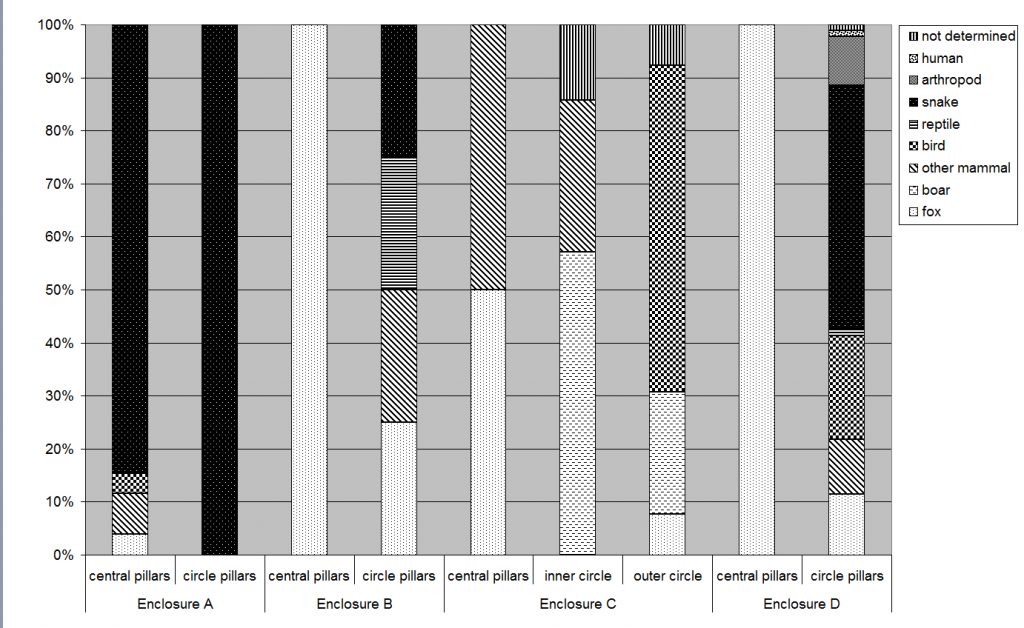

5. Göbekli Tepe’s iconography is actually even more complex than the paper suggests. The animals depicted on the pillars seem to follow an intentional pattern, whereby each building has a different emphasis, i.e. with one animal or more being especially prominent. If we interpret these differences as an expression of community and belonging, this could hint at different groups having been responsible for the construction of particular enclosures. In other words, specific enclosures may have served the needs of different social entities. For this reason, it is extremely problematic to pick out any one pillar and draw far-reaching but isolated interpretations while leaving out its context. A purely substitutional interpretation ignores these subtler but significant details. Details like the headless man on the shaft of Pillar 43, interpreted as a symbol of death, catastrophe and extinction by Sweatman and Tsikritsis, silently omits the clearly emphasised phallus which must contradict the lifeless notion; rather, this image implies a more versatile narrative behind these depictions. It should also be noted that there are even more reliefs on both narrow sides of Pillar 43 which apparently went unnoticed in the study at hand.

Distribution of the appearance of figurative representations in the enclosures of Göbekli Tepe. Note: The different state of excavation as well as chronological depth of construction periods have to be considered; later added graffiti as well as symbolically reduced icons were not included. (Graphic: J. Notroff & N. Becker, DAI)

Pillar 43 from Enclosure D and its particularly rich relief-decoration – actually extending not only on the pillar’s western broadside (left), but also the southern (middle) and northern (right) narrow sides. (Photos: K. Schmidt, N. Becker, DAI)

Pre-Pottery Neolithic iconography, by far exceeding the realms of Göbekli Tepe, is often especially concerned with articulation and disarticulation of the human body. Particularly the depiction of severed human heads or headless bodies in combination with necrophagous animals (preferably but not exclusively vultures) is a well-known theme and may be rooted in a complex multiphase Pre-Pottery Neolithic mortuary ritual. Similar depictions of a bird grasping a human head are known from Göbekli Tepe as well as life-sized human sculpture heads which were deposited within the buildings.

Fragmented sculpture from Göbekli Tepe showing a bird of prey crouched on a human head. (Photo: N. Becker, DAI)

Meanwhile both authors of the orginal study replied to our response (same issue of MAA, see link above), stressing that “… given the statistical basis o[f] [their] interpretation, any interpretation inconsistent with [theirs] is very likely to be incorrect.” (Sweatman and Tsikritsis, Comment, MAA 17(2), 66). Admittedly though, we still would like to express our doubt that human creativity really can be treated as a statistical case solely.

Recent Comments